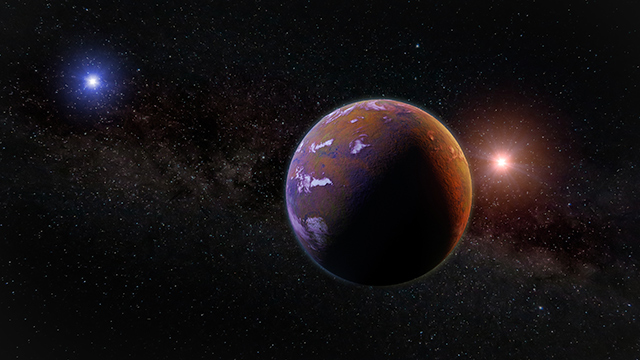

Scientists thought that GJ 1132 b, a distant exoplanet discovered in 2015, lost its atmosphere. But now it seems that it has formed itself a new one. The gases of this new atmosphere suggest a volcanic origin as well.

Scientists at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) Jet Propulsion Laboratory made the discovery after examining existing observations of GJ 1132 b with the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). They gathered the data back in 2017.

Raissa Estrela, a postdoctoral fellow at the lab who was part of the research team, said their finding was "super exciting" because the planet's atmosphere could be a new or a secondary one.

Estrela said she and her colleagues first thought that such irradiated planets as GJ 1132 b could be quite boring since they already lost their atmospheres. But then they found that GJ 1132 b had practically regenerated another one. The paper describing the discovery has been accepted into the Astronomical Journal.

Exoplanet formed a new atmosphere

Exoplanets – planets outside the Solar System – like GJ 1132 b were once enveloped in a hydrogen atmosphere that disappeared over time.

In fact, scientists surmise that most of the barren exoplanets in outer space were once shrouded in thick clouds of hydrogen similar to those found in the atmospheres of gas giants like Neptune and Uranus. Exoplanets usually orbit stars. When those stars explode, the blast may blow away hydrogen in the atmosphere.

The result is sometimes dramatic, so much so that a previously gassy planet could quickly become a bare world approximately the same size as the Earth. "How many terrestrial planets don't begin as terrestrials?" asked Mark Swain, the lead author of the paper.

But as Swain and his colleagues found, GJ 1132 b did not stop there. It formed a new one, which features many gases, including hydrogen and methane. The new atmosphere also has hydrogen cyanide and an aerosol-rich haze, which may resemble the smog found in heavily polluted cities and major industrial regions on Earth.

To better understand what might have happened to bring about this new atmosphere, the researchers analyzed GJ 1132 b's close relationship with its star, which is a red dwarf. (Related: Scientists discover over 1,000 stars where E.T. can observe Earth.)

GJ 1132 b orbits the star so tightly that it completes a circle once every 1.5 Earth days. This proximity keeps the planet tidally locked. This means it shows the same side to the star at all times, just as only one side of the moon is facing the Earth at all times. And as it orbits, the exoplanet soaks up lots of stellar radiation.

Swain and his colleagues suspect that the planet's star was pulling on it strongly enough to heat it dramatically. They surmise that GJ 1132 b is a hot magma "ball" covered by a very thin crust. This crust can be easily cracked like an eggshell.

The pull from the star could have created cracks on the planet's surface, allowing gases to seep out and form an atmosphere.

The researchers hope to test their hypothesis with NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the successor to the HST. It is scheduled to launch this fall. It will allow the researchers to observe the surface of GJ 1132 b in infrared light, which can tell them a lot about the planet's temperature.

Swain said if there are magma pools or volcanic activities going on in some regions of the planet, then those areas should turn up hotter in the JWST. Such pools and activities will also generate more gases. Therefore, Swain and his colleagues may soon be looking at actual geologic activity on GJ 1132 b.

Go to Space.news to learn more about exoplanets and their atmospheres.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.