- Research suggests common childhood infections like measles and chickenpox may build long-term immunity, reducing risks of certain cancers and heart disease.

- The "hygiene hypothesis" proposes that early microbial exposure trains the developing immune system, potentially lowering allergy and asthma rates.

- Studies indicate a history of febrile childhood illnesses is associated with a decreased risk of acute coronary events and mortality from cardiovascular disease.

- Experts caution that the potential benefits do not mean all infections are harmless, emphasizing that severity, timing and a child's underlying health are critical factors.

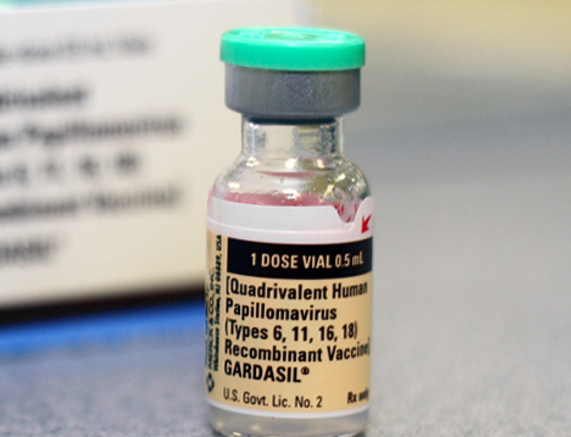

- The long-term immunological impacts of natural infection versus vaccination are an area of ongoing scientific inquiry and debate.

A growing body of scientific research is prompting a provocative question: in the modern quest to suppress every sniffle and fever, are we inadvertently depriving children of crucial immune training that protects against serious diseases decades later? Emerging studies link common childhood infections—and the fevers that accompany them—to a reduced risk of certain cancers, heart disease, asthma and allergies in adulthood. This evidence challenges deeply ingrained parental instincts and public health narratives, suggesting the immune system is built in childhood through exposure, not just through avoidance.

The hygiene hypothesis and immune education

The central theory underpinning this research is the "hygiene hypothesis." It posits that early exposure to a variety of microbes acts as a necessary training ground, teaching the developing immune system to distinguish real threats from harmless substances. A lack of such exposure, due to ultra-clean environments, smaller family sizes and reduced infection rates, may lead to a misfiring immune system prone to allergic and autoimmune reactions.

Epidemiological observations support this. Factors like having older siblings, attending daycare early, living on a farm and having infections like measles are associated with lower rates of allergic disease. This creates a complex public health equation: vaccines and antibiotics have dramatically reduced the burden of severe infectious disease, but their widespread use coincides with a marked rise in asthma and allergy prevalence over the past half-century.

The protective power of fever and infection

Fever itself may be a biologically meaningful component of this immune education. Research indicates fevers in early childhood are associated with a lower likelihood of allergies years later. The surge in immune-signaling proteins during a fever is believed to help modulate inflammatory responses.

More specifically, several studies have found correlations between common childhood illnesses and improved long-term outcomes:

- Lower cancer risk: A Danish study found children with an infection requiring hospital contact in their first two years had a lower cancer risk in early to mid-adulthood. Other research has linked measles with protection against non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and mumps infection with a decreased risk of ovarian cancer.

- Fewer heart events: A study in Atherosclerosis concluded that improved childhood hygiene might partially explain the rise of coronary heart disease. It found the risk of acute coronary events decreased among those with a history of diseases like chickenpox, measles and mumps, with risk lowering further as the number of infections increased.

Navigating parental fear and medical reality

Modern life has lowered parents' tolerance for sick children. Often the main benefit of vaccines, antibiotics and anti-viral treatments is to treat parental anxiety. While they lower severity of infection, the trade-off is seen in rising rates of longer-term chronic illness such as allergies, asthma and autoimmune disease.

That said, experts uniformly stress that context is everything. "Most routine childhood infections are self-limited and part of normal immune development, especially in healthy children" notes integrative pediatrician Dr. Joel Warsh. But not all infections are harmless for every child. The potential long-term benefit does not negate the real, acute dangers some infections pose, particularly to the very young, the immunocompromised, or the malnourished. “You only benefit if the child survives the infection and recovers without serious complications.”

Parental anxiety often drives a rush to medicate fevers. However, guidelines from bodies like the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommend managing fever by focusing on hydration and comfort rather than aggressively lowering temperature. The challenge lies in balancing the immediate well-being of a sick child with an understanding of fever's potential immunological role.

The unanswered questions and the path forward

Much of the evidence linking childhood infections to long-term benefit remains observational and speculative. Crucially, science does not yet fully understand how the immunity derived from a natural infection, which involves a broad innate and adaptive response, compares to the more targeted immunity conferred by vaccines over a lifetime.

The critical question for researchers is not whether infections are simply "good or bad," but under what specific conditions—considering timing, severity, nutrition and genetic background—they might contribute to a more robust immune system later in life. The goal is to determine if the protective effects of early immune challenges can be understood and perhaps replicated in safer ways, without exposing children to the dangers of unmitigated disease.

Reconciling past exposures with future health

This research adds a nuanced layer to our understanding of public health history. It suggests that the dramatic decline of common childhood infections in the 20th century, while saving countless lives from acute disease, may have had unintended consequences for population-wide immune regulation. The conversation now turns to whether modern medicine can integrate this understanding—honoring the complex way the immune system is built in childhood through controlled exposure and resilience—while continuing to protect the vulnerable from the devastating outcomes of serious infection. The path forward requires embracing complexity over simple slogans, recognizing that the story of immunity spans a lifetime.

Sources for this article include:

Please contact us for more information.