It’s been clear for decades that national news organizations such as CNN and the New York Times tend to be biased in favor of social democracy (i.e., “progressivism”) and what we would generally call a “left-wing” ideology. Journalists, for instance, identify as Democrats in far higher numbers than any other partisan group. And political donations by members of the media overwhelmingly go to Democratic candidates.

(Article by Ryan McMaken republished from Mises.org)

This is why even as far back as the 1940s, libertarian and conservative groups felt the need to found their own news sources, publishing houses, and other outlets for the distribution of information.

Similarly, in recent decades, higher education faculty have been shown to be overwhelmingly in favor of the Democratic Party, both in affiliation and in donations. In addition to providing instruction at colleges and universities, these people are the ones who write textbooks, history books, and the scholarly publications that influence other faculty members, secondary school teachers, and current students.

It would be shocking if the net effect of this clear bias were not to push the public—at least those members of the public who view news media broadcasts, read textbooks, and attend college classes—in the direction of the ideology favored by the journalists and professors.

But the means for manufacturing an ideological bias don’t end there. In recent years we have increasingly been seeing other institutions—outside newsrooms and universities—that are taking an active role in shaping the public’s ideology. These include social media firms, and even online sources of information once considered relatively outside the reach of political controversies.

This is what is to be expected when a single ideological group controls educational institutions and major media outlets over a period of several decades. Under these conditions—and unless other institutions provide an effective alternative—the ideology that is dominant within schools and newsrooms will spread to become the ideology of the larger general public. Thus, we should expect to see more and more doctrinaire ideological activism in the larger society, in Silicon Valley and beyond.

Controlling the Message outside the Media and Academia

We’ve seen a few examples of this over the past week. The first example is Twitter’s concerted and admitted effort to hide the NY Post’s exposé on potentially damaging emails from Joe Biden’s son. Twitter’s CEO, Jack Dorsey, first claimed that the company’s efforts to prevent Twitter users from sharing the story were a “mistake” and offered some rather implausible explanations. After the Post and a variety of right-leaning groups expressed outrage over the affair, the company backed down. This is just the latest of many cases of media companies making efforts to edit, curate, and control the information being communicated on their websites.

Another example comes from Wikipedia, where—in spite of the apparent veracity of the Post’s story on Hunter Biden—the claims against Hunter Biden are casually dismissed as “debunked.” No evidence has been presented to support this claim, and the Biden campaign has not denied the claims made in the Post’s story.

A third example comes from the editors at Merriam-Webster (continually updated online). After US Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett used the phrase “sexual preference,” she was denounced for using “offensive” language by US senator Mazie Hirono of Hawaii. This was confusing to many observers, since the term has long been used as a nonpejorative term and has even been used in recent years by both Joe Biden and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

However, by a startling “coincidence,” editors at Merriam-Webster apparently modified the definition of the phrase “sexual preference,” adding the word “offensive” in reference to use of the term following the spat between Barrett and Hirono. Use of the Wayback Machine shows that two weeks earlier the word “offensive” had not been included in the definition.

These examples likely illustrate a growing role for left-wing ideologues outside official news media in shaping and manipulating public opinion for purposes of promoting one political faction over another.

These examples are certainly not the only evidence that companies that deal in internet-delivered data have very clear political preferences. Studies have shown that political donations coming out of Silicon Valley overwhelmingly favor Democrats. At Twitter, from the company’s founding to 2012, 100 percent of political donations made by company employees were to Democrats. In 2016, 90 percent of political donations coming out of Google went to Democrats.

The Natural Outcome of Years of Educational Bias

None of this should surprise us. For decades, the public’s predominant source of information about the nation’s history and political institutions has been the establishment “mainstream” media, public schools, and America’s higher education system.

This has a sizable effect on the public’s views and ideology. Staffers at tech companies, dictionary editors, and managers at Google are all part of this public.

Moreover, the sorts of people who work at Silicon Valley companies, and who work as editors and website designers, tend to have degrees obtained from colleges and universities. These are the same colleges and universities that today’s journalists and pundits attended. They’re the same colleges and universities that public school teachers attended, and which today’s attorneys, corporate CEOs, and high-level managers attended.

Moreover, over time, the share of the public attending these colleges and universities has grown. Fifty years ago, only around 10 percent of Americans completed college. Today, the total is around one-third.

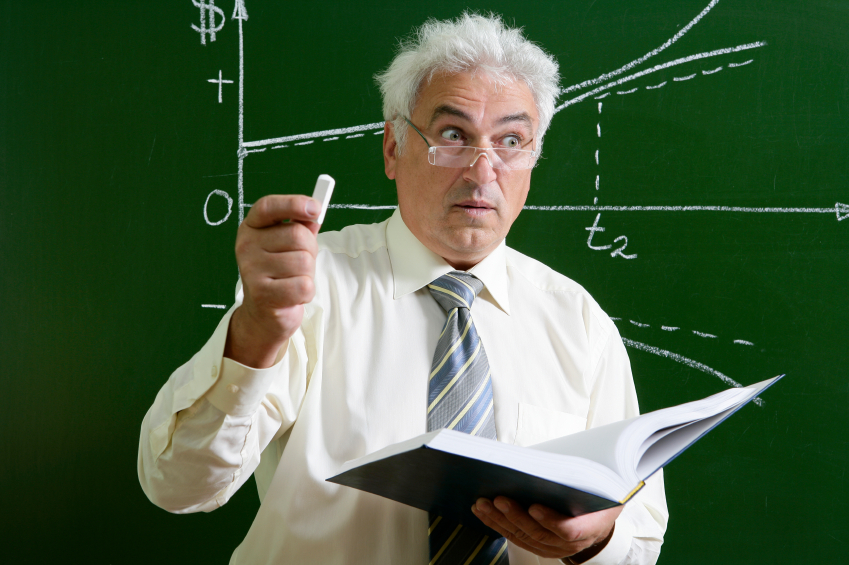

Also not surprising: more schooling apparently tends to translate into more left-wing political views. Data from a wide variety of sources has shown that Americans with more schooling tend to self-identify as “liberal” more often. According to the Pew Research Center, from 1994 to 2015, the percentage of college graduates who were “mostly liberal” or “consistently liberal” increased from 25 percent to 44 percent. At the same time, those who were “mostly conservative” or “consistently conservative” remained almost unmoved, from 30 percent to 29 percent. In other words, the number of college graduates with ”mixed” views has shifted overwhelmingly to the left. This trend is even stronger among Americans who have attended graduate school.

This would seem to be only natural. After all, the faculty has shifted to the left in recent decades. In 1990, according to survey data by the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) at UCLA, 42 percent of professors identified as ”liberal” or ”far-left.” By 2014, that number had jumped to 60 percent. Journalists have moved in the same direction.

So if it seems to you that corporate employees, college grads, and the media-consuming public is moving to the left, you’re probably not imagining things.

Why It’s So Important to Build Institutions That Offer an Alternative

More astute observers of the current scene have long recognized that ”politics is downstream from culture.” In other words, if we want to change politics, we have to change the worldviews of political actors first. For example, if we want a world which reflects a Christian worldview, we need a large portion of the population to actually believe in that worldview. If we want a world where voters and legislators support private property rights, we need a world where a sizable portion of the population was raised and educated to believe private property is a good thing. There are no shortcuts around this.

Unfortunately, the activists who often get the most traction are those who take exactly the opposite position. They offer a ”solution” that involves nothing more than closing the barn door long after the horse has escaped. Yet this position is nonetheless often popular because it offers a quick fix. This position takes this basic form: ”If we can get the right people into political office for the next couple of elections, then everything will be fixed.” Never mind the fact that the ”wrong” people got into office precisely because the voting public had been educated in such a way that they find those politicians’ ideas and positions attractive.

Perhaps the most recent purveyor of this futile and shortsighted view is one-time Trump advisor Steve Bannon. Bannon embraced the idea that ”culture is downstream from politics,” insisting he could deliver a ”permanent majority” in political institutions in opposition to the Left-controlled zeitgeist. All that was necessary, we were told, was to vote for Bannon’s favorite politicians for a few years. Then the public would magically start adopting Bannon’s preferred conservative views. Bannon, however, never offered a strategy any more sophisticated than buying off voters with even bigger welfare programs and crushing government debt. Bannon apparently missed the fact that the votes he needed for this vision had to come from millions of Americans who have already imbibed decades’ worth of major media content and left-wing faculty lectures.

It’s easy to see how Bannon might have thought the message could resonate. After all, we live in a country where millions of self-described ”conservatives” willingly send their children to sixteen years of public schooling and then are mystified when little Johnny comes home and announces he’s a Marxist. Apparently these people are very slow learners.

But Bannon’s more insightful colleague Andrew Breitbart knew better. As noted in a profile of Breitbart for TIME magazine in 2010:

As [Breitbart] sees it, the left exercises its power not via mastery of the issues but through control of the entertainment industry, print and television journalism and government agencies that set social policy. “Politics,” he often says, “is downstream from culture. I want to change the cultural narrative.” Thus the Big sites devote their energy less to trying to influence the legislative process in Washington than to attacking the institutions and people Breitbart believes dictate the American conversation.

Although I often disagreed with Breitbart’s editorial and ideological positions, he was certainly right about how political institutions are changed.

But to accomplish this goal, it is necessary to create organizations and institutions that can offer an alternative to the ”entertainment industry, print and television journalism and government agencies that set social policy.” This requires research, writing, podcasts, and videos. It requires educational institutions (like the Mises Institute’s graduate school) that offer views that go against what is usually taught in universities. It requires revisionist historians and scholars who can write books that counter the views pushed in the endless stream of books and articles churned out by professional academics at state-supported institutions. It requires cultural institutions like churches that provide a compelling intellectual vision that can compete with what’s taught in the colleges.

Until that happens, expect institutions like social media, Wikipedia, the mainstream media, and even corporate America to keep moving left and doing it at an increasingly fast pace. And expect the people who control those institutions to be increasingly hostile to those who disagree with them.

Read more at: Mises.org

Please contact us for more information.