A group of scientists from the Penn State University built a new astronomical spectrograph which provides precise infrared signals from nearby stars. This new technology, called the Habitable Zone Planet Finder (HPF), will allow scientists and astronomers to detect habitable planets well outside the solar system that have liquid water. The HPF is currently housed in the McDonald Observatory at the University of Texas at Austin.

There are infinitely many planets in the universe. However, only a few can possibly support life. For a planet to be classified as habitable, it must satisfy a few conditions:

- It should be in an adequate distance from its star.

- It should not be a gaseous giant.

- It should have a molten core.

- It should hold an atmosphere.

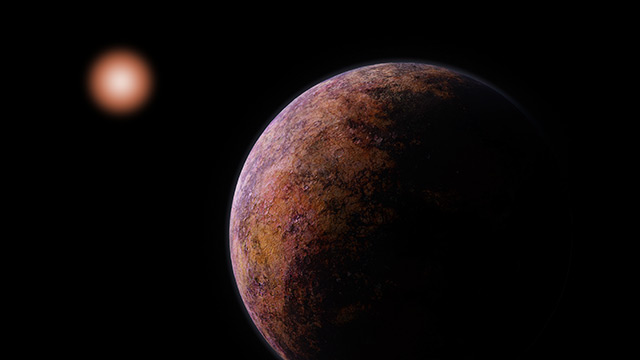

More recently, scientists have also been looking at the presence of liquid water to know if a planet is currently habitable or if it had been in the past. Mars, for example, has geological features that look like dry river and lake beds. This information makes scientists speculate that the Red Planet was once teeming with life. (Related: Scientists discover 15 new planets, including one “super-Earth” that could harbor liquid water.)

Innovation by scientists makes the search for habitable planets easier

In order to find more habitable planets, scientists built the HPF, which will search for planets that revolve around a “cool” star at habitable zones.

A habitable zone is an orbital distance from a star that allows a planet's surface temperatures to be just right – neither scorching nor freezing. It is believed that planets situated in the habitable zone could potentially have liquid water.

The HPF will also help astronomers obtain a star’s radial velocity through minute color changes in a star’s spectra, as an orbiting planet tugs it.

“We are especially interested in finding Earth-like planets that orbit in the habitable zone of the nearest stars,” said Mike Endl, a senior scientist at McDonald Observatory. “These planets around nearby stars represent our best chance to characterize and study them in greater detail. The laser frequency comb at the HPF enables us to reach the high level of precision required to detect these small planets.”

The researchers further described that machines like the HPF built to detect near-infrared wavelengths were challenging to operate. Slight environmental changes, like an increase in temperature, can blind the detector. Therefore, these machines have to run on icy conditions. The technology behind HPF was created to overcome these limitations. By placing the HPF inside a vacuum, constant temperature and pressure are achieved, thereby eliminating outside interference.

“The Habitable Zone Planet Finder was and is a unique opportunity to push beyond the known solutions for finding planets that could potentially harbor life,” said Fred Hearty, senior scientist of astronomy and astrophysics at Penn State and the systems engineer of HPF. “Each advance we have made in the development of this instrument has revealed deeper and more subtle challenges.”

Principal investigator of the HPF project Suvrath Mahadevan attributed the success of the device to the members of the team.

“We would not have been able to push these astrophysical limits without pushing technical and engineering limits here on the ground, or without the hard work, commitment and creativity of graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, research associate, faculty, and industry partners who have worked on HPF for almost a decade,” said Mahadevan.

“These results will pave the way to breaking barriers in the near-infrared, enabling discovery of terrestrial-mass planets in Habitable Zones.”

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.