KELT-9b is a hot find in more ways than one. Not only is this exoplanet hotter than any other planet and many stars, its atmosphere is also the first to show the presence of both iron and titanium, an article in Space.com reported.

This unique alien world dwells within the constellation Cygnus. The light reflected from its scorching atmosphere takes 620 years to reach Earth.

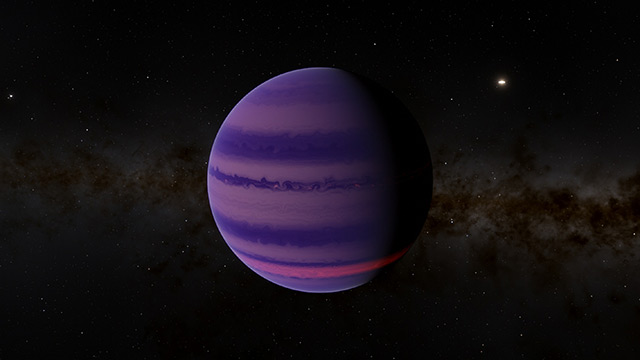

It has twice the diameter and three times the mass of Jupiter. It is also much closer to its parent star, the late B-type main sequence star KELT-9, which partially accounts for its heat.

Astronomers designate it as a "hot Jupiter," a gas giant exoplanet that is hot enough to be mistaken as a star. They have recorded KELT-9b reaching temperatures as high as 7,800 F (4,300 C).

That is more than twice the minimum temperature required to be a hot Jupiter. This planet is also hotter than many actual stars. (Related: A dark hole planet? Astronomers find a “Hot Jupiter” that absorbs almost all light that hits it.)

An exoplanet so hot, it reveals the presence of iron and titanium

Thanks to KELT-9b's intense temperature, researchers from the University of Geneva were able to detect iron and titanium in its atmosphere. This is the first instance that these elements were confirmed to be present on an exoplanet.

The research team had earlier studied the atmosphere of the hot Jupiter for the presence of hydrogen. Another team led by Kevin Heng pored over the same data, but this time they were looking for iron and titanium.

Iron is one of the most common elements in the universe. However, they tend to get trapped inside other molecules. The resulting oxides hide the presence of iron from scrutinizing instruments.

The heat of KELT-9b, however, is so intense that clouds simply cannot form in its atmosphere. Iron atoms can therefore remain independent from other atoms, making them easier to spot.

Titanium oxides have previously been detected in the atmospheres of other exoplanets. However, its pure atomic form has only been seen in KELT-9b.

By looking at the spectrum of light given off by a planet or star, researchers can determine the elements present. Since planets did not give off their own light, Heng and company used recorded data of a solar transit, an event where an exoplanet crossed in front of its home star.

Element-hunting technique can be used to seek out alien life

Heng's team relied on powerful computers and the expertise of astrophysicist Simon Grimm from the University of Bern. They were able to obtain concrete evidence that iron and titanium atoms were present in the atmosphere of KELT-9b.

They also found signs of other elements on the planet. While they remain mum about the details, they have indicated their desire to use the Hubble Space Telescope to look for water.

In addition to confirming the presence of those two elements, the technique they used could be used to look for signs of organic life.

"This is the same technique that we will use to detect signatures of biology, or biosignatures," explained Heng in a blog post. "On Earth, we think it's oxygen and a few other obscure molecules, but we don't know what biosignatures are in general."

If they could figure out the signatures of these biomolecules, he believes his team's technique can be adopted to look for them in planets that were cooler and smaller than KELT-9b, which is too hot to support life. They also want to catalog every chemical on the planet, as well as learn more about its weather.

If you are on the lookout for more articles about hot Jupiters like KELT-9b, investigate Cosmic.news.

Sources include:

Nature.com [PDF]

Please contact us for more information.