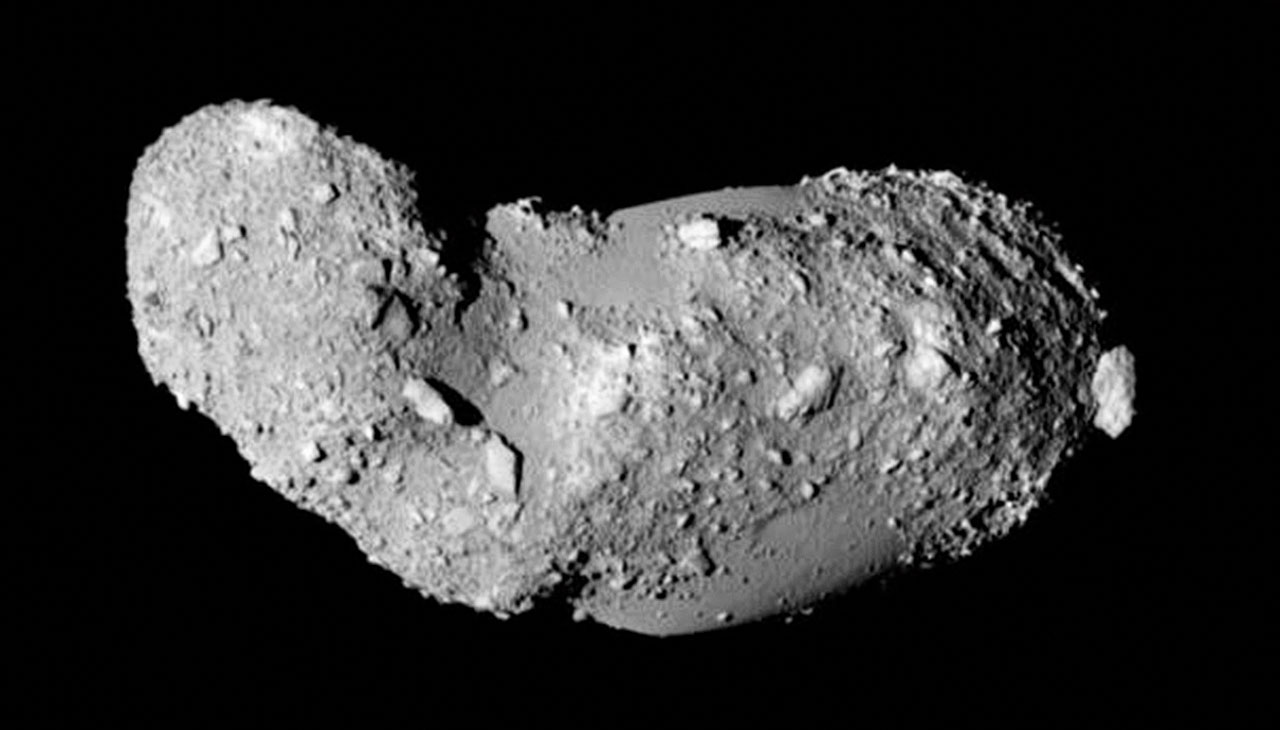

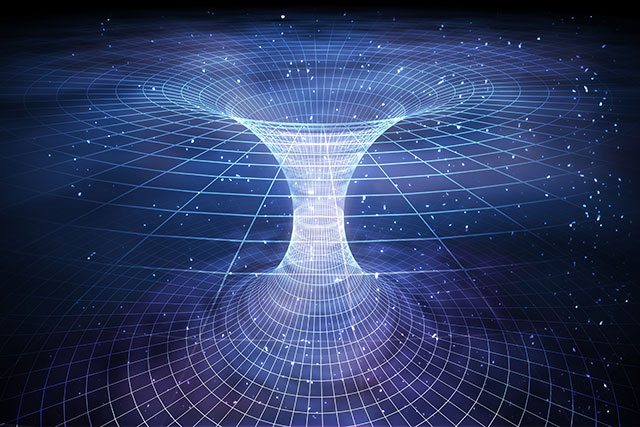

Wormholes are the even more mysterious but nicer sibling of black holes. They're both massive yet invisible distortions in space-time that swallow up anything that gets too near them. They even leave similar "shadows," and according to a LiveScience article, the "smooshed" oblong shadow cast by a wormhole can be detected by radio telescopes.

If you fall into a black hole, it will tear you apart, crush you endlessly, and then add your mass to its own. A wormhole, on the other hand, will send you to another part of the universe like Asgard's Bifrost from the Marvel superhero movies.

This potential for faster-than-light travel makes wormholes a staple of science fiction. So how do you tell one from a black hole?

Both wormholes and black holes are regions of space-time that are so warped that light can no longer travel through them in a straight line. Instead, photons swerve around them, which results in a ring of light forming around them. However, photons that get too close to a wormhole or a black hole fall into it. The only thing they leave behind are dark patches called "shadows." Whereas black holes leave circular patches of darkness, wormholes have bigger oblong shadows that are "smooshed." The shape is how you tell the space-time tunnel from the cosmic dead end. (Related: Scientists are actually losing ground on their understanding of dark matter, as new research contradicts previous findings.)

Radio telescopes could look for slightly oblong-shaped shadows

Astronomers are devising ways to directly observe black holes like the super-massive one at the heart of the Milky Way galaxy. For example, they synchronized radio telescopes around the world to "create" the massive Event Horizon Telescope.

These techniques could be used to look for wormholes like the one proposed by researcher Rajibul Shaikh of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR). Shaikh recently published a paper about a specific type of rotating wormhole that casts a bigger shadow than a black hole.

In his paper, Shaikh said that earlier studies failed to account for the effect of the part of the wormhole that connects its two ends. This "throat" part is what accounts for the spin and therefore the different shape of the shadow.

The existence of stable wormholes could indirectly prove a different theory of gravity or the existence of exotic matter. Einstein's theory of general relativity says gravity would force a wormhole to collapse immediately unless the latter had a way to cancel it. The only way to do so is through anti-gravity, which needs theoretical "exotic matter."

A stable wormhole that doesn't need exotic matter would break our current theory of gravity, said Shaikh, who limited his analysis to a single class of wormholes. He adds that additional research would be required to find out if his theory also applied to other classes.

Some physicists say exotic matter don't help one bit

At least one physicist is unconvinced by Shaikh's theory. John Friedman of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee scoffs at the idea of large wormholes. Even if it's true, he claims they would be impossible to spot or measure.

To measure a shadow, a researcher needs the shape of the space-time fabric around the wormhole. According to Shaikh's theory, that shape is controlled by exotic matter. Since no one knows what exotic matter is, no one can tell the shape of the space-time fabric or the shadow, Friedman argues.

He also points out that Shaikh chose a class of wormholes with a simpler and unrealistic symmetry. Friedman thinks a more realistic wormhole would not fall under the purview of that analysis.

Want to uncover more mysteries of the universe? Visit Cosmic.News.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.