Advertisement

(NationalSecurity.news) It’s “unofficially” official: Cold War II is underway, as recent moves by the U.S., NATO and Russia are proving.

As reported by Defense One, the U.S. government’s recent pledge to fund upgrades to Iceland’s Keflavik military airfield is no small deal for a small ally. Rather, the improvements will make it possible for the U.S. Navy’s new P-8 Poseidon maritime surveillance and patrol aircraft to keep closer tabs on Russia’s increasingly submarine activity in a region rising in importance thanks to fresh and rising tensions between Washington and Moscow.

“In short, the Greenland-Iceland-UK gap is back,” Defense One reported.

The gap was vitally important during the first Cold War, especially to the British navy, which has shrunk dramatically since. From the beginning of World War II in 1939, the German navy used the gap to break out from bases in northern Germany and from occupied Norway after 1940.

During the Cold War the gap represented a line of sorts that Soviet and Warsaw Pact vessels would need to cross in order to halt U.S. reinforcements crossing the Atlantic Ocean. It was also the area Soviet nuclear submarines would need to pass through in order to get into position to launch nuclear missiles at the U.S. and other parts of Europe. For that reason, the U.S. and NATO spent considerable funds and efforts to ensure the gap remained as impenetrable as possible.

In particular much of the effort was focused on anti-submarine warfare capabilities, as well as intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance. Maritime patrol aircraft from Norway, the UK and the U.S. – Navy P-3 Orion aircraft flying out of Keflavik – watched from above as nuclear and conventional subs monitored undersea. Also, an advanced network of undersea censors that had been placed to detect and track Soviet subs monitored the gap as well.

However, after Cold War I ended the GIUK gap was no longer a priority for NATO, let alone a concern. U.S. forces departed Iceland in 2006, and the UK – facing budget pressures – retired its fleet of maritime patrol aircraft in 2010 (The Netherlands retired theirs in 2003, Defense One noted). Maritime security and anti-submarine warfare were no longer priorities as the alliance faced a series of low-intensity conflicts in places like Bosnia, Iraq and Afghanistan.

But Russian activity is changing that paradigm once again.

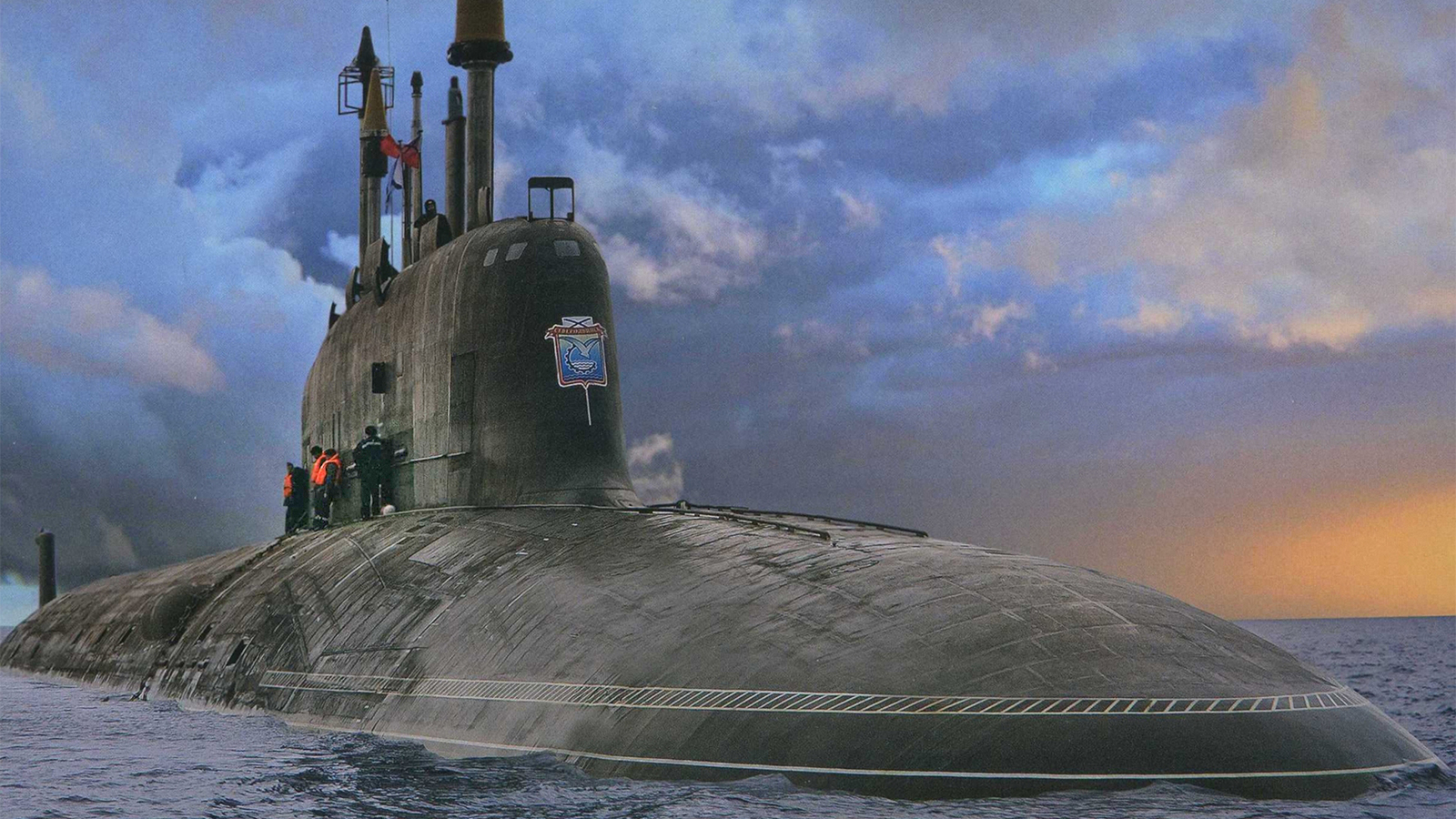

Moscow is investing heavily in its naval forces in particular, building advanced new submarines and other maritime assets. As Defense One reported further:

Moscow is introducing new classes of conventional and nuclear attack submarines, among them the Yasen class and the Kalina class, the latter of which is thought to include air-independent propulsion. AIP, which considerably reduces the noise level of conventional submarines, was until recently seen only in Western navies’ most capable conventional subs.

Mostly, Russia is beefing up its sub force in the Northern Fleet, which is based in Murmansk and is home to Moscow’s sub-based nuclear deterrent. The base is used mostly to patrol the Atlantic and the Arctic.

In the past year the UK, Sweden and Finland have each launched operations to hunt suspected Russian submarines deep in their territorial waters [but were unsuccessful]. Russia has even used its subs to launch deep missile strikes in Syria.

As Russia refurbishes and replenishes its Northern Fleet capabilities, especially its submarine fleet, the U.S. and the UK are refocusing their efforts on keeping the GIUK gap open. Part of that includes upgrading Keflavik.

Britain has said it would seek to rebuild its maritime surveillance aircraft fleet, mostly likely by buying P-8 aircraft from Boeing. Norway may do the same, and is also looking at buying a new class of submarines and just upgraded a signal intelligence ship with new U.S. sensors.

See also:

Submit a correction >>

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

Advertisement

Advertisements