Advertisement

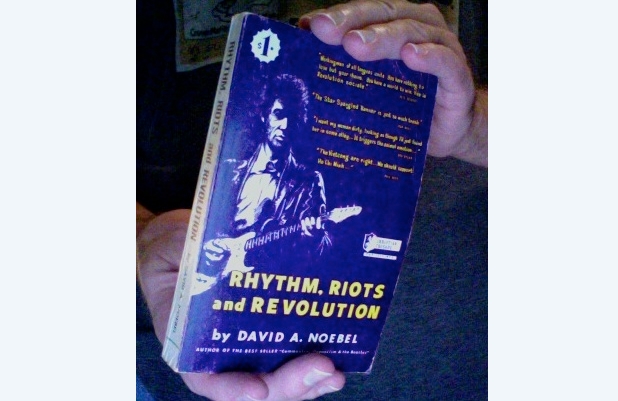

This new year marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of Reverend David A. Noebel’s Rhythm, Riots, and Revolution (R3 for short) — a landmark piece of work for conspiracy theorists.

Noebel hit the scene in 1965 with his conspiratorial pamphlet Communism, Hypnotism and the Beatles, which a year later he expanded into R3, a full-length book of 252 pages, supplemented with footnotes, appendices and facsimile reproductions of government documents, newspaper clippings and personal correspondence. (In 2010, R3 and Noebel’s subsequent musical writings were republished as You Can Still Trust the Communists to be Communists, Socialists, Statists, and Progressives Too).

Rock and roll, jazz, and even some European classical music had previously been condemned for being inspired by the music of “savages.” Rock music, on the other hand, had been redbaited since its inception. Noebel, however, was the first to synthesize it into a single theory.

His thesis was that “Communists have a master music plan” to destroy America, and he traced it back to Communist psychological operations (PsyOp) tactics during the Korean War. In the early 1950s, American journalist Edward Hunter coined the term “brainwashing” and published books on the subject. Central to Hunter’s journalism was Russian scientist Pavlov’s famous psychological experiments with “classical conditioning.” Hunter claimed that Pavlovian methods were being used by the Chinese Communists to brainwash their enemies; Noebel claimed that Pavlovian methods were being used by the Beatles to brainwash and destroy American youth through “the most cunning, diabolical conspiracy in human history” (p.75).

As Noebel explained, “The music has been called a number of things, but today it is best known as rock ‘n’ roll, beat music, or simply Beatle-music” (p.77). In the aftermath of Beatlemania, “all major record companies are flooding our teenagers with a noise that is basically sexual, un-Christian, mentally unsettling, and riot-producing. The consequences of this type of ‘music’ are staggering” (p.79).

Noebel did not actually accuse the Beatles (or other purveyors of Beatle-music) of intentionally promoting the master plan. Neither did he accuse them of being outright Commies, admitting that “it must be stated that this writer has no proof that the Beatles are identifiable Communists” (p.101). But he did accuse Beatle-music of combining Pavlovian rhythms with politically and morally incorrect lyrics: “Not only is the ‘beat’ of the music harmful, but many of the lyrics are subversive.” These lyrics, he said, are “rude, profane, vulgar, pornographic, uncouth, smutty, anti-Christ, atheistic, agnostic, anti-Pope” (p.98). Wisely, he did not actually quote any lyrics, which, as of 1966, did not come close to fitting his description. Songs like “Yesterday” and “Eleanor Rigby” hardly seem like the recipe for destroying America. Instead, he judged the lyrics based on the band’s public statements —especially those of John Lennon, “the religious spokesman for the Beatles” (p.96).

But what made Beatle-music rhythmically Pavlovian, Noebel claimed, is the fact that it had roots in non-Western culture. “The goal is to inundate the American people with African music!” he warned with his usual exclamation point. “The full truth is that it goes still deeper—the heart of Africa, where it was used to incite warriors to such a frenzy that by nightfall neighbors were cooked in carnage pots!” (p.78). As mentioned, early rock and roll had been condemned in very similar terms by Alabama conspiracist Asa Carter and others, and anti-jazz sentiment during the 1920s was rampant. Compare, for example, Noebel’s “carnage pots” to this 1925 letter printed in the Literary Digest: “The noisy beats of jazz-bands are merely a disguised and modern form of the ton-toms of old, which incited savages to fury and fired the fierce energy of cannibals.”

Ultimately, liberals and conservatives alike dismissed Reverend Noebel as a kook, but he was correct about rock music being subversive. And people who really cherish liberty and freedom think that’s a good thing.

As the Neil Young song goes, “Keep on rockin’ in the free world.”

Source used:

Submit a correction >>

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

Advertisement

Advertisements