- A study published in Nature by Chinese meteorologists analyzed tropical cyclone activity over 30 years using the Power Dissipation Index (PDI), which measures storm intensity, duration, and frequency. The findings reveal no increase in cyclone destructiveness globally, with a notable decline in the South Indian Ocean basin since 1994.

- The study contradicts claims by climate activists and media outlets, such as World Weather Attribution and The Guardian, which often attribute severe weather events like Cyclone Chido to climate change. The data does not support assertions that cyclones are becoming more frequent or intense due to global warming.

- Cyclone activity has decreased in the South Indian Ocean due to atmospheric stability and shifting storm locations. Globally, the PDI shows steady or declining trends in most ocean basins, challenging the narrative that warmer oceans lead to more destructive storms.

- Critics, including science writer Roger Pielke Jr., argue that "weather attribution science" often relies on assumptions rather than robust evidence. Tropical cyclones are influenced by complex factors like vertical wind shear and ocean cooling, making simplistic climate-driven claims misleading.

- The media's reliance on computer models and activist press releases, such as the BBC's 2024 weather report, often exaggerates climate impacts without evidence. This disconnect raises concerns about whether climate science is being distorted to serve political agendas rather than fostering honest, data-driven discourse.

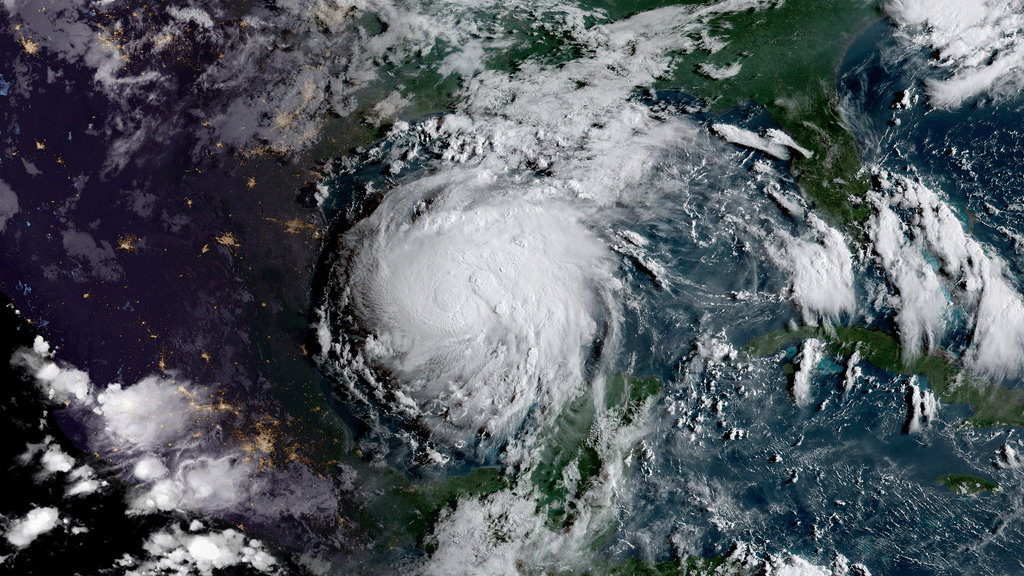

In the relentless drumbeat of climate alarmism, one claim has become a staple of the environmentalist narrative: hurricanes are growing more frequent and more powerful due to human-caused climate change. But what if the data tells a different story? What if the facts, rather than fearmongering, reveal a trend that contradicts the doomsday predictions? A groundbreaking study published in Nature last December does just that, offering a sobering reality check for those who insist on tying every weather event to the so-called "climate emergency."

The study, conducted by a team of Chinese meteorologists, analyzed tropical cyclone activity over the past 30 years using a metric called the Power Dissipation Index (PDI). Unlike single-measure indicators, the PDI combines storm intensity, duration, and frequency, providing a more comprehensive assessment of cyclone destructiveness. The findings are striking: there has been no increase in the destructive power of cyclones – a category that includes hurricanes and typhoons – in any ocean basin over the past three decades. In fact, the South Indian Ocean basin has seen a dramatic decrease in both cyclone frequency and duration since 1994.

This revelation stands in stark contrast to the claims of climate activists and their media allies, who routinely attribute every severe weather event to global warming. For instance, when Cyclone Chido struck Mayotte and Mozambique last year, causing significant damage and loss of life, organizations like World Weather Attribution (WWA) and outlets like The Guardian were quick to assert that such storms are becoming more likely and intense due to climate change. Yet, as the Nature study demonstrates, the data simply does not support these assertions.

The downward trend in cyclone activity is particularly pronounced in the South Indian Ocean, where atmospheric stability and changes in cyclone locations have contributed to reduced frequency and duration. Globally, the cumulative PDI shows a steady or declining trend across most ocean basins, including the North Atlantic. This challenges the narrative that warmer oceans are inevitably leading to more destructive storms.

Climate science is complicated by politics

So why does the media continue to push the opposite story? Much of it stems from the rise of "weather attribution science," a controversial field that attempts to link individual weather events to climate change. Critics like Roger Pielke Jr., a respected science writer, have labeled this approach "weather attribution alchemy," arguing that it relies on assumptions rather than robust evidence. Pielke notes that tropical cyclones are influenced by a complex interplay of factors, including vertical wind shear and ocean surface cooling, which make simplistic claims about climate-driven intensification misleading.

The media's reliance on computer models and press releases from activist organizations further muddies the waters. For example, the BBC's end-of-year weather report for 2024 claimed that extreme weather events, including hurricanes and droughts, were becoming more frequent and severe due to climate change. Yet, as climate analyst Paul Homewood pointed out, the report provided no evidence to support these claims. Official data shows no increase in the intensity of tropical cyclones, and rainfall in the Amazon has actually increased by five percent over the past 30 years.

The disconnect between the data and the narrative raises important questions about the role of science in public discourse. Are we witnessing a genuine effort to understand climate dynamics, or is there a systematic campaign to distort the facts in service of a political agenda? As Pielke suggests, the proliferation of extreme weather attributions may be driven by demand from the media and advocacy groups, rather than by a commitment to scientific rigor.

The Nature study serves as a reminder that climate science is ever-evolving, and that reality is often more nuanced than the headlines suggest. While it is essential to address environmental challenges, doing so requires an honest assessment of the data – not the perpetuation of alarmist myths. As the evidence shows, hurricanes and cyclones are not becoming more frequent or powerful. It’s time to set aside the fearmongering and focus on facts, not fiction.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.