A new study suggests that Mars may be harboring microbial life beneath its surface. Published April 15 in the journal Astrobiology, the study shows that the same chemical reactions that support microbial communities beneath Earth's surface can also occur in the Martian underground.

One of those reactions is radiolysis, which occurs when radioactive elements within rocks react with water locked in pore and fracture space. The reaction breaks water down into its constituent hydrogen and oxygen molecules. The hydrogen molecule is then dissolved in the remaining water while minerals like pyrite (fool's gold) absorb the oxygen molecules to form sulfate minerals. Microbes can then use the dissolved hydrogen as fuel and the oxygen preserved in the sulfates to "burn" that fuel.

On Earth, these "sulfate-reducing" microbes have been found in places such as Canada's Kidd Creek Mine, where they thrive more than a mile beneath the surface.

For their study, the researchers wished to determine whether Mars harbor the ingredients for radiolysis, namely, sulfide minerals that could be converted into sulfate, radioactive elements like thorium and uranium, and rock units with sufficient pore space to trap water.

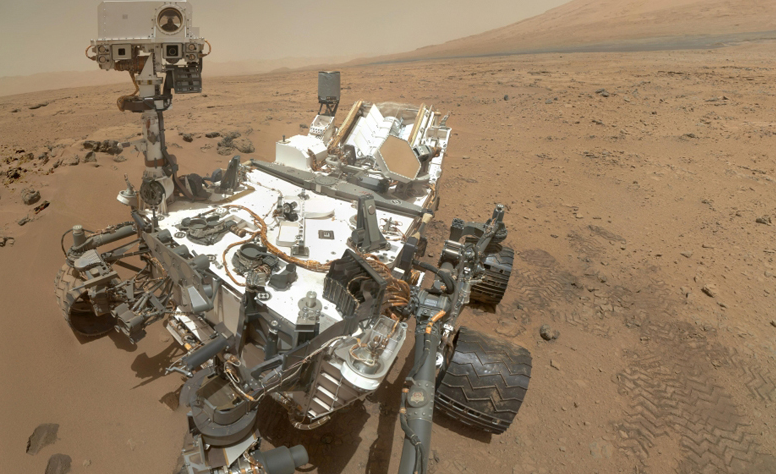

To that end, the team examined data from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) Curiosity rover, as well as other spacecraft orbiting the Red Planet. They also incorporated data on Martian meteorites into their analysis.

They found that all of the ingredients are present in several different types of Martian meteorites in adequate abundance to support Earth-like habitats. Regolith breccias, which are meteorites sourced from crustal rocks that date back to more than 3.6 billion years ago, have the highest potential for supporting life.

The researchers noted that, unlike Earth, Mars lacks a plate tectonics system to continually recycle crustal rocks. This meant that the Red Planet's ancient terrains remain largely undisturbed.

Jesse Tarnas, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who led the study while completing his doctorate at Brown University, remarked that microbial life might exist in the Martian subsurface wherever there is groundwater. Given that Martian rocks contain the ingredients necessary to fuel radiolysis, Mars might have enough chemical energy to support subsurface microbial life, he explained.

"We don't know whether life ever got started beneath the surface of Mars, but if it did, we think there would be ample energy there to sustain it right up to today," Tarnas added.

The researchers recommended exploring the subsurface of Mars when searching for evidence of alien life. As past studies showed, there is reason to believe that groundwater exists to this day. A study published last year, for example, found evidence of four subsurface lakes a mile beneath the Martian south pole. (Related: Scientists find evidence of an underground water system on MARS – could it have supported alien life?)

"The subsurface is one of the frontiers in Mars exploration," Jack Mustard, a professor of environmental and planetary science at Brown and one of the study's researchers. "We've investigated the atmosphere, mapped the surface with different wavelengths of light and landed on the surface in half-a-dozen places, and that work continues to tell us so much about the planet's past."

"But if we want to think about the possibility of present-day life, the subsurface is absolutely going to be where the action is," he went on.

For more studies supporting the presence of Martian life, follow Space.news.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.