Complete suppression of immune response may be the real cause of death among coronavirus patients, claim two new studies led by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis (WUSTL).

Previous reports point to severe inflammation as the main cause of organ damage suffered by patients with severe COVID-19. But autopsy findings tell a different story: Despite the presence of large amounts of the virus in the organs of deceased patients, researchers found severely low levels of immune cells, particularly small white blood cells called lymphocytes.

This depletion suggests that the immune system of these patients were inhibited from mounting a proper response. The new studies, therefore, propose restoring immunity to infected individuals using interleukin-7 (IL-7), a small signaling protein (cytokine) that helps start off inflammation. Besides boosting lymphocyte counts, IL-7 also has documented antiviral effects.

Coronavirus and the immune system: Is it instigation or suppression?

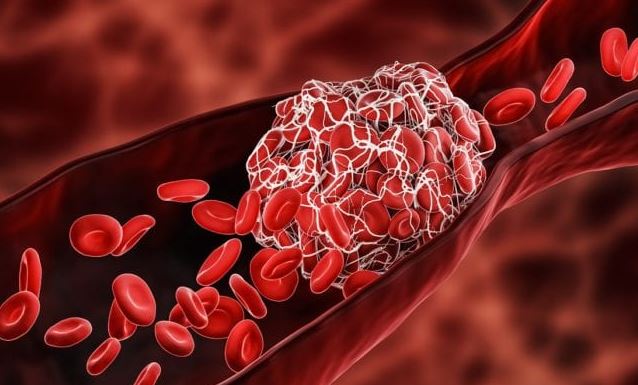

The earliest studies on COVID-19 all report a phenomenon called a cytokine storm. During an infection, cells release SOS signals in the form of cytokines. These signaling molecules coordinate immune response by activating immune cells and recruiting circulating white blood cells to the site of infection. This series of events constitutes part of the immune response known as inflammation.

Under normal circumstances, cytokine production is regulated so that inflammation is short-lived. But some infections cause cytokine production to go into overdrive, resulting in hyperinflammation. This cytokine storm is a common complication of COVID-19 that not only aggravates acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), but also leads to multiple organ failure.

Recently, however, evidence of immunosuppression in COVID-19 cases has emerged, with some studies calling the disease a lymphocyte killer. Clinical studies report profound and protracted lymphopenia, or abnormally low lymphocyte counts, in severe COVID-19 cases, particularly in the spleen. This organ normally contains special white blood cells that help the body fight infections by filtering out infected red blood cells.

Autopsy reports also describe a devastating depletion of lymphocytes in deceased patients, as well as a reduction in the numbers and function of certain antiviral immune cells. This immune collapse is accompanied by other telltale signs of an incapacitated immune system, such as high viral loads in the lungs and the presence of virus-induced cellular abnormalities in other organs.

But the most compelling evidence of immunosuppression is the occurrence of secondary hospital-acquired infections in patients with COVID-19. Collectively, these findings suggest that while hyperinflammation happens initially, immunosuppression follows and ultimately decides patient outcomes. Uncontrolled immune response may not be what kills critically ill patients, but the reduced ability of their immune system to protect them from the virus. (Related: Experts: A balanced, optimal immune system is key to avoiding coronavirus.)

A new therapy that can boost immunity

Two separate studies led by WUSTL researchers, Richard Hotchkiss and Kenneth Remy, explored a new therapy that can boost immunity against the coronavirus by increasing circulating and tissue lymphocytes. This treatment makes use of IL-7, a cytokine that's currently undergoing clinical trials for cancer-related and infectious disorders, as well as for COVID-19.

Besides being an antiviral agent, studies have shown that IL-7 can normalize lymphocyte counts and function while decreasing viral loads in patients with life-threatening infections. IL-7 also improves the activation of T cells – immune cells responsible for killing infected cells – without triggering a cytokine storm. IL-7 therapy has been tested against bacterial sepsis and has produced promising results without causing adverse effects.

In an article published in JAMA Network Open, Hotchkiss, Remy and their colleagues reported that IL-7 treatment restored lymphocyte counts in critically ill COVID-19 patients with severe lymphopenia. The cytokine was injected twice a week into the muscles of these patients for two weeks. A total of 13 COVID-19 patients receiving standard-of-care treatment served as controls for the experiment.

The researchers said that IL-7 was well-tolerated by the patients and blood analyses showed no changes in the concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines during treatment. At day 30, 11 of the 13 controls developed secondary infections, while only seven of the 12 IL-7-treated patients developed the same. Those who received IL-7 shots ended up having lymphocyte counts twofold greater than the controls.

In another study, which appeared in JCI Insight, Hotchkiss and Remy worked with a different team to determine if IL-7 can restore T-cell function in COVID-19 patients. They reported that those infected by the coronavirus not only have very low numbers of circulating T cells, but that the functions of these immune cells, which include producing cytokines like interferon-gamma (IFN-y), are severely reduced.

The researchers noted that IFN-y is important for both adaptive and innate immunity as it serves as an activator of specialized immune cells, which could deal with infections more effectively. Using immune cells isolated from COVID-19 patients, they showed that IL-7 treatment can restore function to impaired immune cells. Exposure to IL-7 nearly doubled the number of IFN-y-producing T cells collected from COVID-19 patients in culture.

Strategies that can boost the immune system can help people during pandemics, says Hotchkiss. He also believes that making the immune system stronger is key to fighting off the coronavirus. Both he and Remy agree that interventions focused on inhibiting the immune system, which include the use of anti-inflammatory drugs like NSAIDs, are not what COVID-19 patients need.

“When we actually looked closely at these patients, we found that their tires, so to speak, were underinflated or immune-suppressed,” said Remy. “To go and poke holes in them with anti-inflammatory drugs because you think they are hyperinflated or hyperinflamed will only make the suppression and the disease worse.”

For more updates on coronavirus research, visit Science.news.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.