Studying the Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19) has been difficult due to how infectious the virus is and the need to keep researchers safe. To work around this, scientists have developed a virus that acts just like the coronavirus but doesn’t cause severe disease.

Currently, any laboratory research of SARS-CoV-2 – the pathogen behind COVID-19 – requires a high level of biosafety. Researchers work inside laboratories with multiple containment levels and specialized ventilation systems, all while wearing bulky full-body biohazard suits with pressurized respirators.

While necessary, these safety measures limit who can research the coronavirus to those labs that can afford the necessary equipment. This slows down efforts to find medicines and cures for the virus.

“Hybrid” virus created to make research safer

To allow researchers and institutions who don’t have access to the necessary biosafety equipment to contribute to the fight against the coronavirus, researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have created a new “hybrid” virus that infects cells and interacts with antibodies just like how the SARS-CoV-2 does. Unlike the latter, however, this new virus does not cause any severe illness.

The researchers used another virus, called a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), as a base for the new hybrid virus. VSV is a workhorse in virology labs since it’s easy to manipulate genetically while, at the same time, being fairly innocuous. The virus primarily infects animals such as horses, cattle and pigs. When it does occasionally infect people, it only causes a mild, flu-like illness that lasts from three to five days.

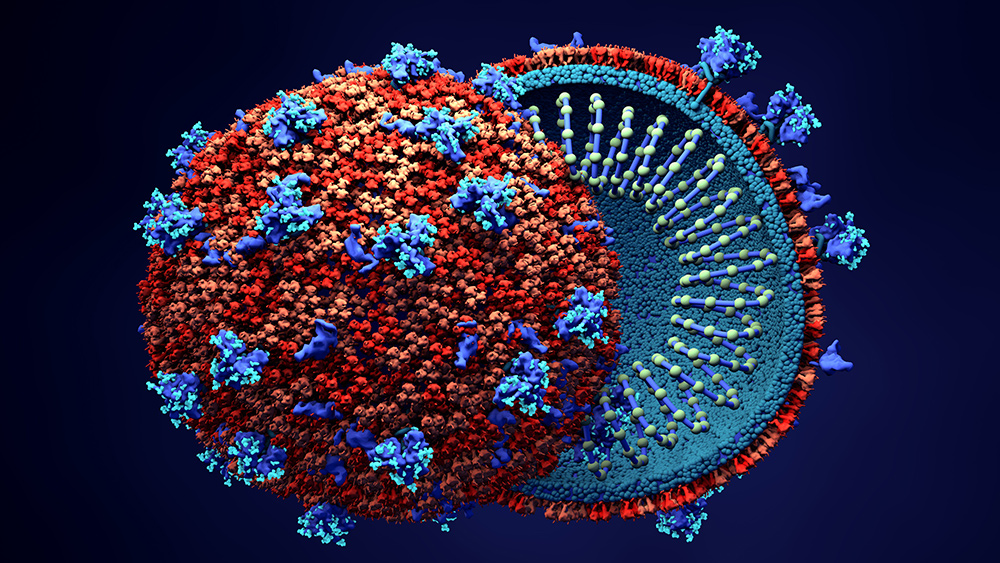

Aside from being less deadly, one of the main differences between VSV and SARS-CoV-2 is how they infect cells. While viruses in general use proteins on their surface to attack cells, the latter uses what scientists have dubbed a “spike” protein.

To create the hybrid virus then, the scientists removed VSV’s surface protein gene and replaced it with the one from SARS-CoV-2. The resulting hybrid, dubbed VSV-SARS-CoV-2, has the coronavirus’ spike protein, allowing it to target cells in the same manner, but lacks the genes needed to cause severe illness.

Once they had the new virus, they tested it against antibodies from COVID-19 survivors. The test shows that the antibodies reacted to the hybrid virus in the same way that they did against the real SARS-CoV-2 virus. At the same time, antibodies that worked against the VSV-SARS-CoV-2 also worked against SARS-CoV-2. (Related: Most coronavirus patients develop “neutralizing antibodies” after recovery, but are they enough to head off another infection?)

“Humans certainly develop antibodies against other SARS-CoV-2 proteins, but it’s the antibodies against spike that seem to be most important for protection,” said co-senior author Dr. Sean Whelan. “So as long as a virus has the spike protein, it looks to the human immune system like SARS-CoV-2, for all intents and purposes.”

New virus will supposedly accelerate the development of treatments

According to the team, this new hybrid virus could help more scientists evaluate a range of preventative treatments for COVID-19 that are based on neutralizing antibodies.

“One of the problems in evaluating neutralizing antibodies is that a lot of these tests require a BSL-3 facility, and most clinical labs and companies don’t have BSL-3 facilities,” explained Dr. Michael S. Diamond, co-senior author of the study.

“With this surrogate virus, you can take serum, plasma or antibodies and do high-throughput analyses at BSL-2 levels, which every lab has, without a risk of getting infected. And we know that it correlates almost perfectly with the data we get from bona fide infectious SARS-CoV-2,” he added.

According to Diamond, the hybrid virus could be used to test to see where or not an experimental vaccine triggers the creation of neutralizing antibodies, to measure whether a COVID-19 survivor carries enough of these antibodies to donate plasma to other COVID-19 patients or even identify if any antibodies have the potential to be developed into antiviral medicines.

In addition to being useful for expanding research on SARS-CoV-2, the fact that the hybrid virus has the same spike protein as the latter and triggers the same antibodies means that it could possibly also be used as a vaccine. According to Diamond, he and his colleagues are already conducting animal studies to evaluate the possibility.

Whether or not the hybrid VSV-SARS-CoV-2 virus can be effective as a vaccine is another matter altogether.

Vaccines work by using a virus, or something similar to it, to trigger the immune system to the production of antibodies against it. Studies have shown, however, that antibodies the body produces to fight SARS-CoV-2 tend to fade after just a few months. This means that the immunity provided by any COVID-19 vaccine – not just that based on the hybrid virus – will likely not last for long.

Learn more about the efforts to develop treatments against COVID-19 at Pandemic.news.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.