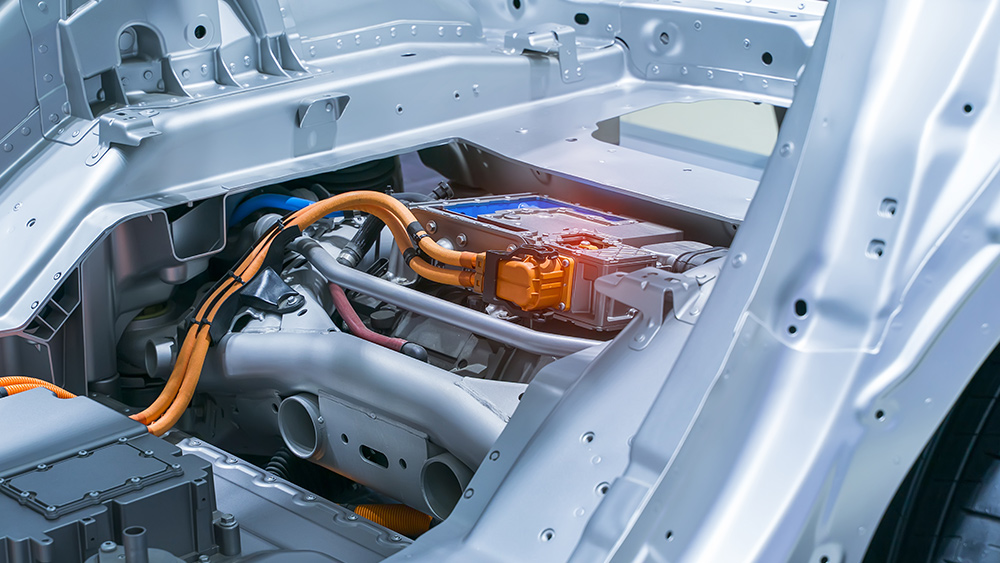

The world's running on batteries – lithium-ion batteries, to be precise. Over the past 20 years, global production for lithium has tripled, with lithium-ion batteries found in many of today's technological devices – from smartphones to pacemakers, and even cars. Despite their long list of real-world applications, lithium-ion batteries are still limited in what they can do, especially when it comes to battery life.

Researchers from the University of Tokyo, however, found a way to improve battery life using a more common element – sodium. In their paper, published in Nature Communications, the team discussed how creating a battery using a sodium-derived model material can lead to better and longer-lasting batteries.

"This means batteries could have far longer life spans, but also they could be pushed beyond levels that currently damage them," explained Atsuo Yamada, a research scientist at the University of Tokyo and a co-author of the study. "Increasing the energy density of batteries is of paramount importance to realize electrified transportation."

An award-winning battery can still be problematic

Lithium-ion batteries haven't been around for very long. While the first functional lithium-ion battery was developed in the early '70s, it took 30 more years before the batteries became commercially available. It didn't take long before they marked the beginning of a new era in electronics. These days, lithium-ion batteries aren't just ubiquitous, they play a key role in society.

Their developers – John Goodenough of The University of Texas (UT) at Austin, Stanley Whittingham of Binghamton University in New York, and Akira Yoshino of Meijo University in Japan – have even been awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work.

Indeed, lithium-ion batteries are nothing short of revolutionary, but they're riddled with problems – chief of which is battery life. This is very noticeable in mobile phones and laptops: New devices can last a full day or more on a full charge, but older models just last for a little under five hours before their batteries get fully depleted. This becomes a bigger issue when it comes to electric vehicles since battery life can impact their range and performance.

In a separate review, researchers from China highlighted that the main challenge in lithium-ion batteries, especially when it comes to their use in electric vehicles, is the formation of solid electrolyte interface (SEI) films during the charging process. Over time, this contributes to a drop in battery capacity, which ultimately shortens battery life.

A force enough to keep stacks together

In the current study, the team developed a battery using a model material called oxygen redox-layered cathode (Na2RuO3). This sodium-based battery, according to the researchers, performs similarly to lithium-ion batteries when it comes to energy storage and discharge. But what sets the team's battery apart is its ability to “repair” itself with use. This is because of a force called Coulombic attraction, which removes any deviations from how the oxide ions are stacked during charge and discharge.

The researchers noted that the attraction produced in the model battery is greater than the Van der Waals force. While this type of force is found in intermolecular attractions, they wrote in their report that it isn't enough to maintain the structure needed in lithium-ion batteries to sustain its energy discharge.

From these findings, the team is hopeful that it can lead to more applications, including stabilizing other compounds. (Related: Latest lithium-ion battery uses water-salt solution, reducing risk of fire and explosion in household electronics.)

Scientific.news has even more stories on the advancements of lithium-ion batteries.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.