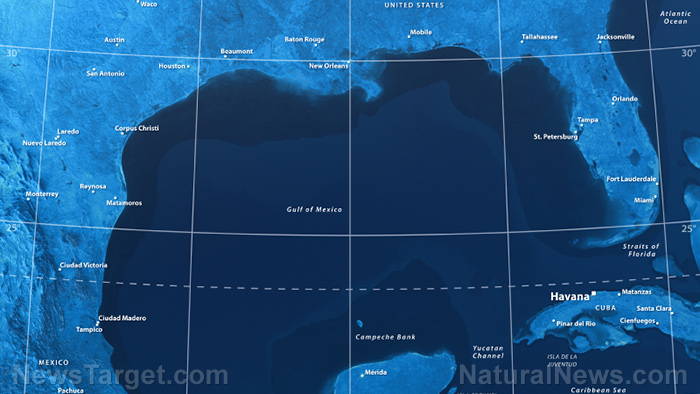

Remember when British Petroleum (BP), Halliburton, and ConocoPhillips indiscriminately dumped tens of thousands of gallons of Corexit into the Gulf of Mexico to supposedly remedy the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil disaster? Well according to experts, this nasty chemical concoction is still floating around in that giant "bathtub," and is actually now eating away at a submerged German U-boat that was sunk back in 1942 during World War II.

Photographic evidence reveals that the sunken Nazi vessel has basically become an all-you-can-eat buffet for the microscopic chemical byproducts of Corexit that are reportedly now feeding on the U-166, which was only recently discovered in 2001, "at an accelerated rate," according to scientists.

Researchers from the University of Southern Mississippi (USM) say that, after Corexit's anaerobic bacteria feed on the carbon and sulfur in crude oil, they generate a waste product that's capable of corroding metal, which is exactly what's happening to the sunken German U-166.

"The metal loss has accelerated after the spill and that's very unusual," stated USM Professor Leila Hamdan to New Scientist about the strange phenomenon.

Under normal circumstances, a sunken vessel like the German U-166 would experience its worst corrosion in the immediate aftermath of its submersion, followed by a gradual decline over time. But in this case, the presence of Corexit has cause the ship's corrosion rate to dramatically accelerate, increasing more than five times in the four years following the disaster compared to six years prior.

To further demonstrate the strangeness of the situation, Prof. Hamdan and her team placed a series of metal discs on the Gulf seabed, both near where the Deepwater Horizon spill took place, as well as in a spot roughly 80 kilometers away. After 16 weeks, the discs closest to the spill lost three times as much metal compared to the other discs, proving that Corexit really is the gift that keeps on giving, just like many observers warned it would be.

"We can't say for sure what is in the sediment around the submarine," says Jennifer Salerno, one of the team members from George Mason University (GMU). "But we do know the change was down to the oil."

Salerno and her colleagues are eager to return to the U-166, seeing as how the last time they captured photos of it was back in 2013. There's no telling how much worse the corrosion has gotten in the years since – nor can anyone really say for sure what additional damage all of this lingering Corexit is causing to the complex ecosystems present in the Gulf.

"Given the historical and cultural significance of the U-166, we should go back," Salerno contends. "The deep sea is a place that not a lot of us can connect with, and this gives us a reason to care."

Did BP permanently destroy the Gulf of Mexico?

In November 2012, BP, which owned the Gulf oil rig that exploded, killing 11 workers and spilling roughly 72 million gallons of crude oil into the gulf, was barred from performing any new government work in the United States. The company also plead guilty to criminal charges and agreed to pay a $4.5 billion fine.

"The disaster left lingering oil residues which have altered life in the ocean by reducing biodiversity in sites closest to the spill," the Daily Mail Online (United Kingdom) reports. "Scientists are still trying to figure out where all the oil went and what effects it had ... It is regarded as the worst environmental catastrophe in U.S. history."

For more news about industrial chemicals that are destroying our environment and world, be sure to check out Chemicals.news.

Sources for this article include:

Please contact us for more information.