Advertisement

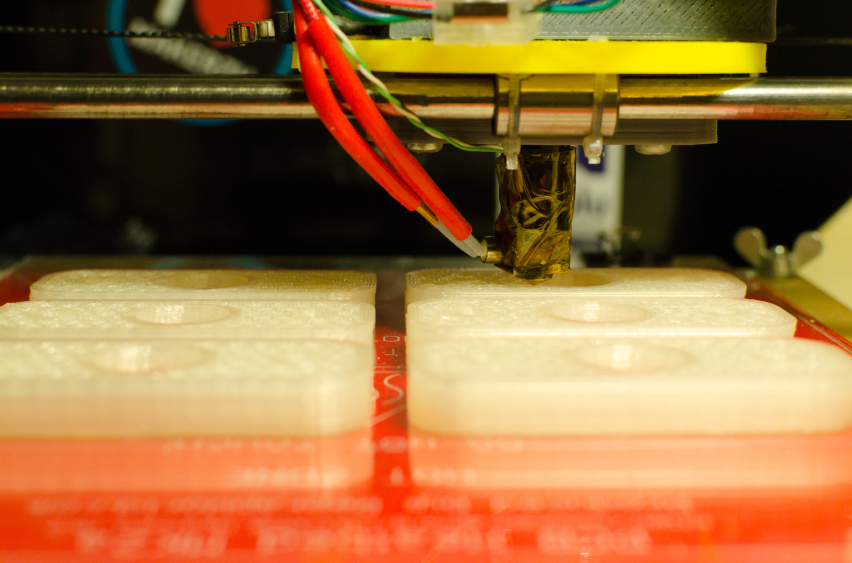

3D printing is very versatile, but a printer takes time to raise all those layers of plastic filaments. A recently developed light-based additive technique promises to work 100 times faster when it comes to turning plastic additives into complex shapes and parts.

Developed by the University of Michigan, the new technique will make it easier and cheaper for 3D printing to fulfill production orders for fewer than 10,000 items. It will remove the need for an expensive mold that can cost up to thousands of dollars, only to be discarded once the last part of the lot has been made.

The most common form of 3D printing builds a complex shape by laying down layer after one-dimensional layer of molten material. This process is excruciatingly slow for jobs that need to be completed within one or two weeks.

A manufacturer will need hundreds of 3D printers to fulfill even a relatively small order in such short time. And a 3D printer isn’t exactly cheap, either. (Related: Scientists have found a way to fabricate replacement parts within hours using only water bottles and other recyclable materials.)

The first 3D printer capable of literal 3D printing

Michigan researchers Timothy Scott and Mark Burns were aware of the drawbacks of 3D printing. They pooled together their knowledge of chemical engineering to resolve this problem.

In their technique, a pair of lights manipulate how the liquid resin cools down and solidifies. The light-based technique lets the resin be shaped in much more complex patterns compared to conventional additive manufacturing systems.

Using the new process, a 3D printer can create a three-dimensional shape in a single shot. In comparison, an ordinary printer needs to build up multiple 1D lines or 2D cross-sections to create a similar shape.

Scott and Burns demonstrated the speed and versatility of their method by printing a lattice, a toy boat, and a block. Burns called it one of the first additive machines that are capable of true 3D printing.

The description is not mere hyperbole. The modified device overcomes the primary limitation of vat-based additive methods, where the liquid resin solidifies on the illumination window that admits the light. This tendency halts the printing job almost as soon as it begins.

The light-based 3D printer makes a fairly big area that is free of solidification. It can use thicker resins and manufacture tougher objects, especially if the resin incorporates strengthening powder additives. Furthermore, the objects printed with this method have better structural integrity than those made by filament 3D printing.

Two lights are better than one – or an oxygen-permeable window

An earlier attempt to solve the solidification-on-window issue involves making the illumination window permeable to oxygen. The gas will keep the resin from solidifying near the window, ensuring that the printed surface can be pulled away from the surface.

However, the oxygen-permeable window only works if the resin is very runny. In turn, products printed from such thin resins are fairly fragile. This restricts vat 3D printing to making dental devices, shoe insoles, and other items that will not be treated roughly.

Instead of a special window, the Michigan-developed 3D printing method uses a second light. Two lights working together can create a bigger gap between the object and the window, allowing the resin to flow much faster.

Furthermore, Scott and Burns included a photo-inhibitor to the resin. The additive material already contains a photoactivator that causes it to turn solid when exposed to light, but the photo-inhibitor responds to a different wavelength of light. The use of two different wavelengths of light allows the resin to be hardened at any 3D place near the illumination window.

Sources include

Submit a correction >>

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

Advertisement

Advertisements