Advertisement

A recent measles outbreak in Los Angeles County reveals the limitations of California’s strict new compulsory vaccination law, health experts say.

A 2014 measles outbreak traced back to Disneyland infected 145 people in the United States, Canada, and Mexico. In reaction, California passed a law requiring all children in public and private schools to be fully vaccinated, with only medical exceptions permitted. The law, which took effect in July, makes California one of only three states that do not accept personal or religious exemptions to vaccine requirements.

The first measles case in the new outbreak was diagnosed in L.A. County in early December. Since then, 19 more people have been infected, 17 of them in the same county.

Small, contained outbreak

To contain the outbreak, county health officials interviewed every infected person to learn everywhere they had gone and everyone they had interacted with during the period in which they were most likely to be contagious. Officials then attempted to figure out who else might have been exposed, such as by scanning patient lists at emergency rooms that had been visited.

Officials then contacted 2,000 people who might have been exposed to the virus. About 10 percent had not been vaccinated against measles, and nearly all of these accepted vaccination or another prophylactic treatment.

Because the current outbreak was confined to a limited social circle, it was relatively easy to trace and contain, said Dr. Jeffrey Gunzenhauser, interim health officer for the L.A. County Department of Public Health. Of the 18 infected people in L.A. County, 15 had at least one clear social connection.

But health officials are still remaining cautious, he said.

“They could’ve driven and let’s say they stopped at a gas station — somebody could’ve gotten exposed.” (RELATED: See more news about infectious disease outbreaks at Oubreak.news)

“Full compliance” impossible to achieve

Public health experts were open about the ways that the case demonstrates the weaknesses of the new compulsory vaccine law, SB 277. They noted that people infected in the recent outbreak ranged in age from young children to senior citizens, and that the most well-represented group was people in their 20s. Other than young children, none of these people will be affected by the new law.

That’s because SB 277 takes advantage of the state’s control over schooling to require vaccination for all schoolchildren. To avoid a bureaucratic nightmare, however, the law only requires vaccine checks at kindergarten and seventh grade. Children in between those ages may have several years before being forced to comply. And while the University of California system has voluntarily agreed to follow the same rules set by SB 277, many people leaving high school will never have their vaccination status checked again. Nor is there any mechanism in place to check the status of people who have already left school.

In other words, actually achieving “full vaccine compliance” across all ages would require a degree of intrusiveness that would be politically untenable, if not outright unconstitutional. Thus SB 277 cannot produce “herd immunity” against measles until nearly all unvaccinated people above the age of 12 have died!

Notably, California never had much of a vaccine compliance crisis to begin with. It is estimated that prior to the passage of SB 277, 94.5 percent of kindergartners were already vaccinated against measles. However, because measles are so contagious, a vaccination rate of 96 to 99 percent is required for herd immunity to function (to protect those who cannot be vaccinated for reasons considered valid by the medical establishment).

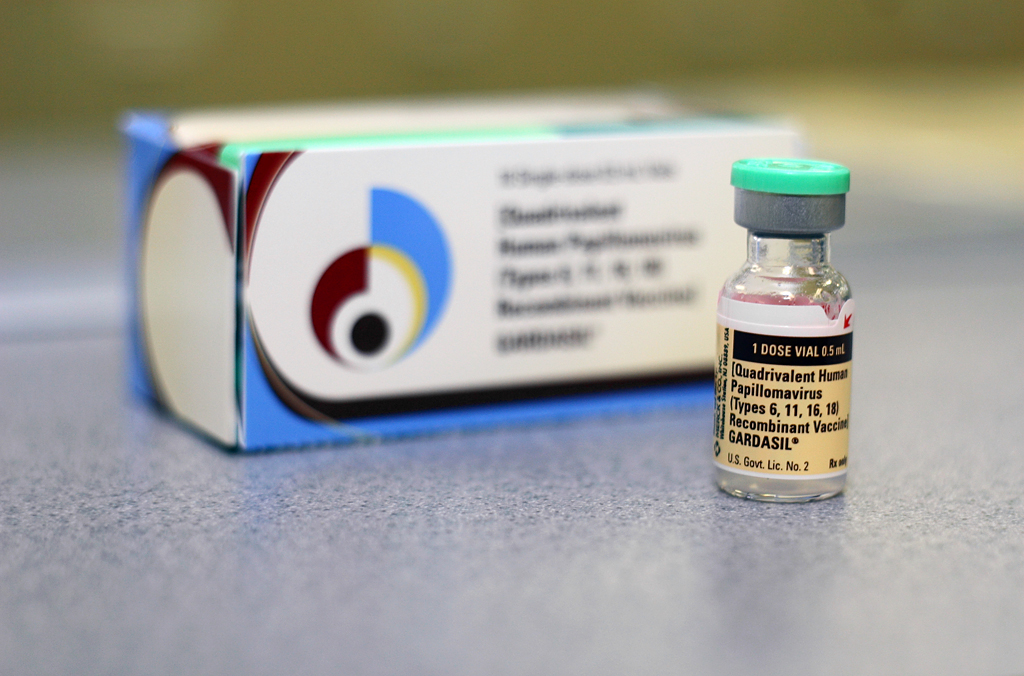

It’s unclear if such a high rate of compliance is even a feasible goal. Looking just at the contraindications for the MMR vaccine listed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and vaccine manufacturer Merck, people who should not get the shot include those with immunodeficiency, those with a family history of immunodeficiency, and those with severe allergies to any component in the vaccine, including gelatin or the antibiotic neomycin. Collectively, these people might well total 1 percent or more of the population.

Also see CDC.news for more news about infectious disease.

Sources for this article include:

Submit a correction >>

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

Advertisement

Advertisements