Advertisement

The military seized her photographs, quietly depositing them in the National Archives, where they remained mostly unseen and unpublished until 2006

Article by Tim Chambers

Dorothea Lange—well-known for her FSA photographs like Migrant Mother—was hired by the U.S. government to make a photographic record of the “evacuation” and “relocation” of Japanese-Americans in 1942. She was eager to take the commission, despite being opposed to the effort, as she believed “a true record of the evacuation would be valuable in the future.”

The military commanders that reviewed her work realized that Lange’s contrary point of view was evident through her photographs, and seized them for the duration of World War II, even writing “Impounded” across some of the prints. The photos were quietly deposited into the National Archives, where they remained largely unseen until 2006.

I wrote more about the history of Lange’s photos and President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 initiating the Japanese Internment in another post on the Anchor Editions Blog.

Below, I’ve selected some of Lange’s photos from the National Archives—including the captions she wrote—pairing them with quotes from people who were imprisoned in the camps, as quoted in the excellent book, Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment.

I’ve also made a limited number of prints of her photos available for sale at Anchor Editions, and I’m donating 50% of the proceeds to the ACLU—they were there during WWII handling the two principal Supreme Court cases, fighting against the government’s mass incarceration of Japanese-Americans—and they have pledged to continue to fight against further unconstitutional civil rights violations. Their fight seems especially important today given the current tide of anti-Muslim rhetoric, and talk of national registries and reactionary immigration policies.

“A photographic record could protect against false allegations of mistreatment and violations of international law, but it carried the risk, of course, of documenting actual mistreatment.”

— Linda Gordon, Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment

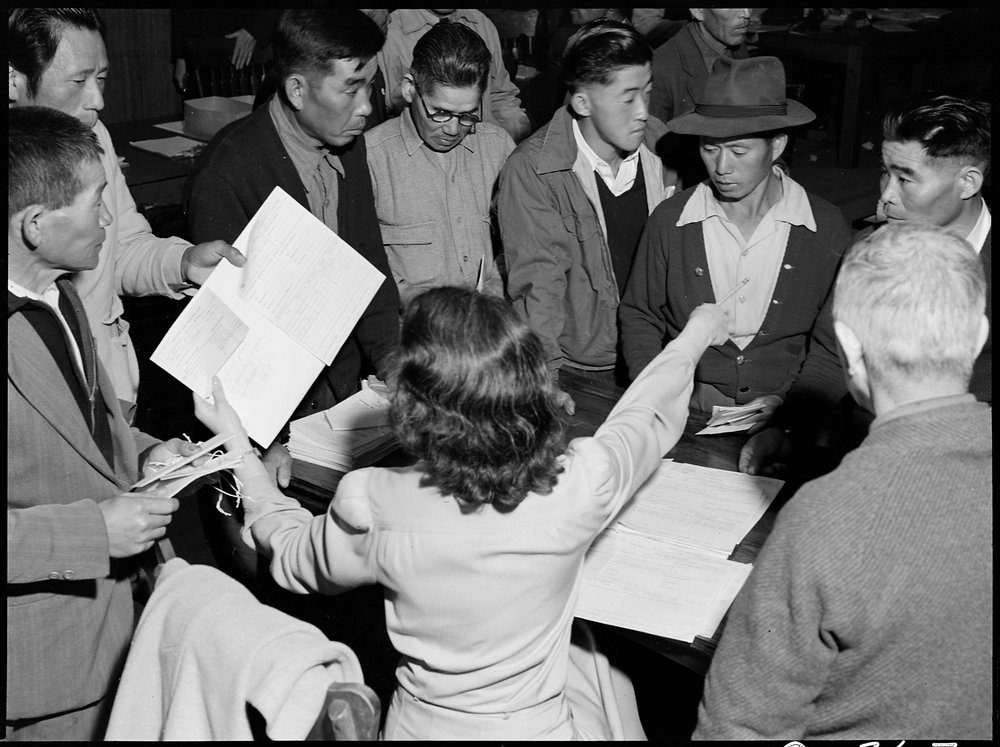

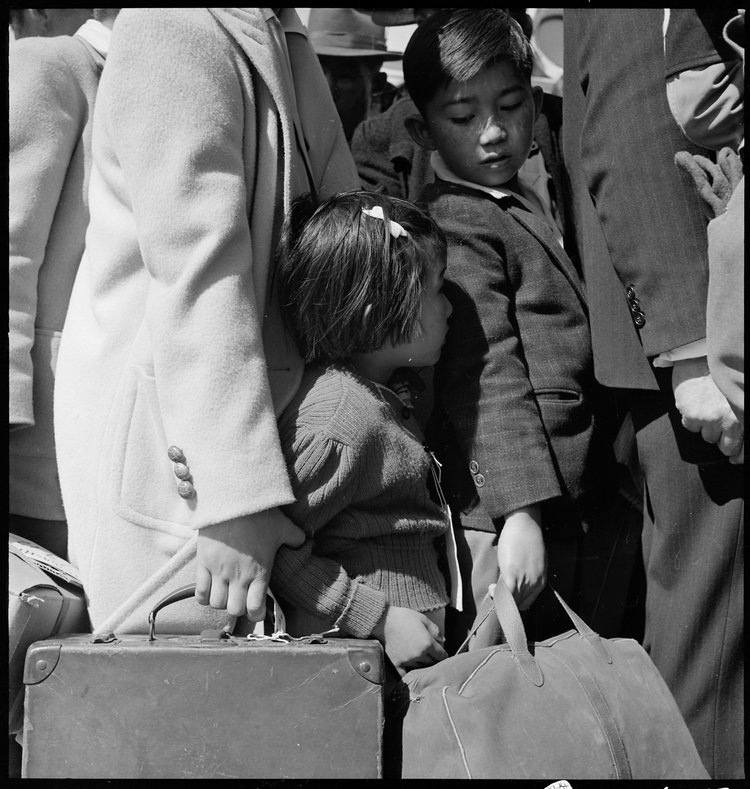

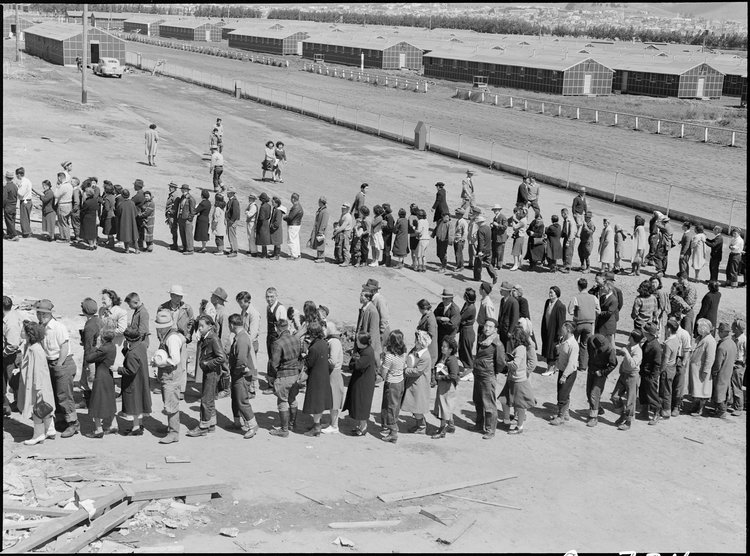

San Francisco, California. Residents of Japanese ancestry appear for registration prior to evacuation. Evacuees will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

“We couldn’t do anything about the orders from the U.S. government. I just lived from day to day without any purpose. I felt empty.… I frittered away every day. I don’t remember anything much.… I just felt vacant.”

Original caption: Hayward, California. Members of the Mochida family awaiting evacuation bus. Identification tags are used to aid in keeping the family unit intact during all phases of evacuation. Mochida operated a nursery and five greenhouses on a two-acre site in Eden Township. He raised snapdragons and sweet peas. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

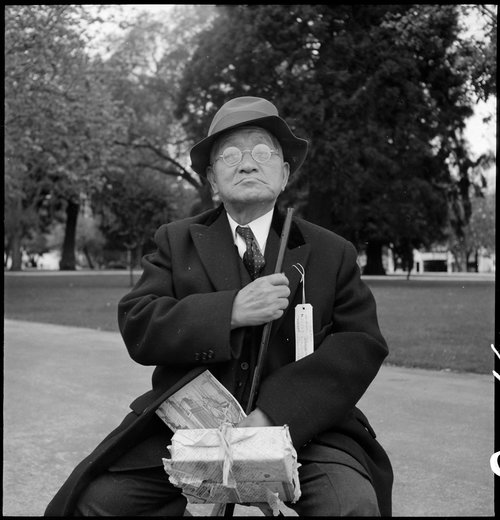

Hayward, California. Grandfather of Japanese ancestry waiting at local park for the arrival of evacuation bus which will take him and other evacuees to the Tanforan Assembly center. He was engaged in the Cleaning and Dyeing business in Hayward for many years.

Byron, California. These field laborers of Japanese ancestry at Wartime Civil Control Administration Control Station are receiving final instructions regarding their evacuation to an Assembly center in three days.

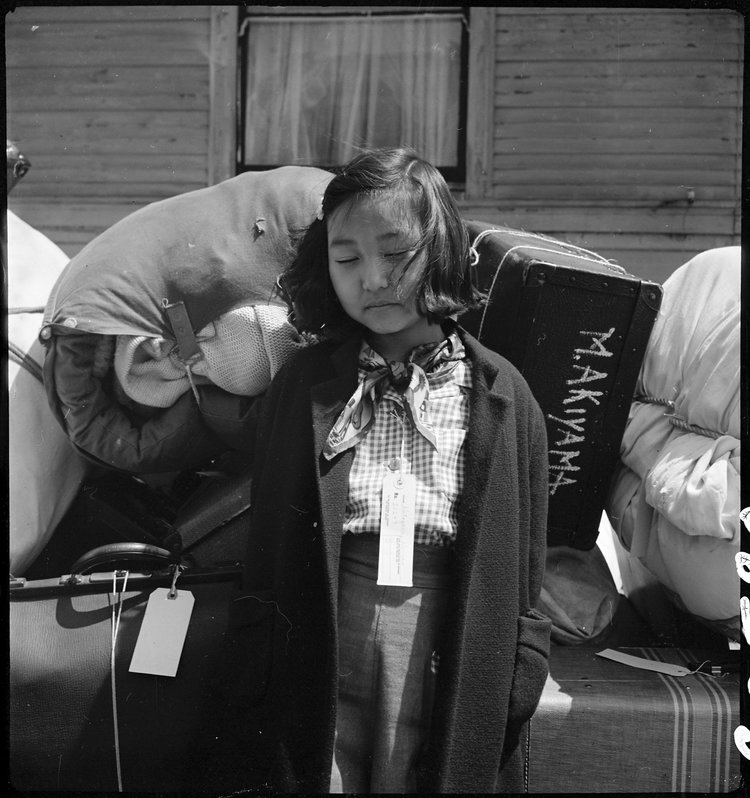

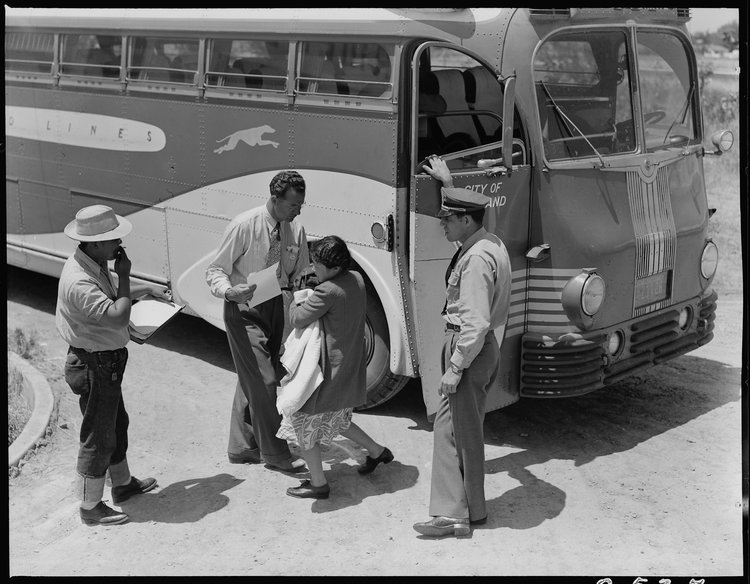

“As a result of the interview, my family name was reduced to No. 13660. I was given several tags bearing the family number, and was then dismissed…. Baggage was piled on the sidewalk the full length of the block. Greyhound buses were lined alongside the curb.”

— Mine Okubo, Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno

Oakland, California. Kimiko Kitagaki, young evacuee guarding the family baggage prior to departure by bus in one half hour to Tanforan Assembly center. Her father was, until evacuation, in the cleaning and dyeing business.

Byron, California. Third generation of American children of Japanese ancestry in crowd awaiting the arrival of the next bus which will take them from their homes to the Assembly center.

- San Francisco, California. A young evacuee arrives at 2020 Van Ness Avenue, meeting place of first contingent to be removed from San Francisco to Santa Anita Park Assembly center at Arcadia, California. Evacuees will be transferred to War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

- Hayward, California. Baggage of evacuees of Japanese ancestry stacked at public park as evacuation bus prepares to leave for Tanforan assembly center. Evacuees will be transferred later to War Relocation Authority centers where they will spend the duration.

- Centerville, California. This farmer rearranges his personal effects as he awaits evacuation bus. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for duration.

- Hayward, California. Baggage of evacuees of Japanese ancestry ready to be loaded on moving van. Evacuees will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

- San Francisco, California. An early comer arrives with personal effects at 2020 Van Ness Avenue as part of the contingent of 664 residents of Japanese ancestry, first to be evacuated from San Francisco on April 6, 1942. Evacuees will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

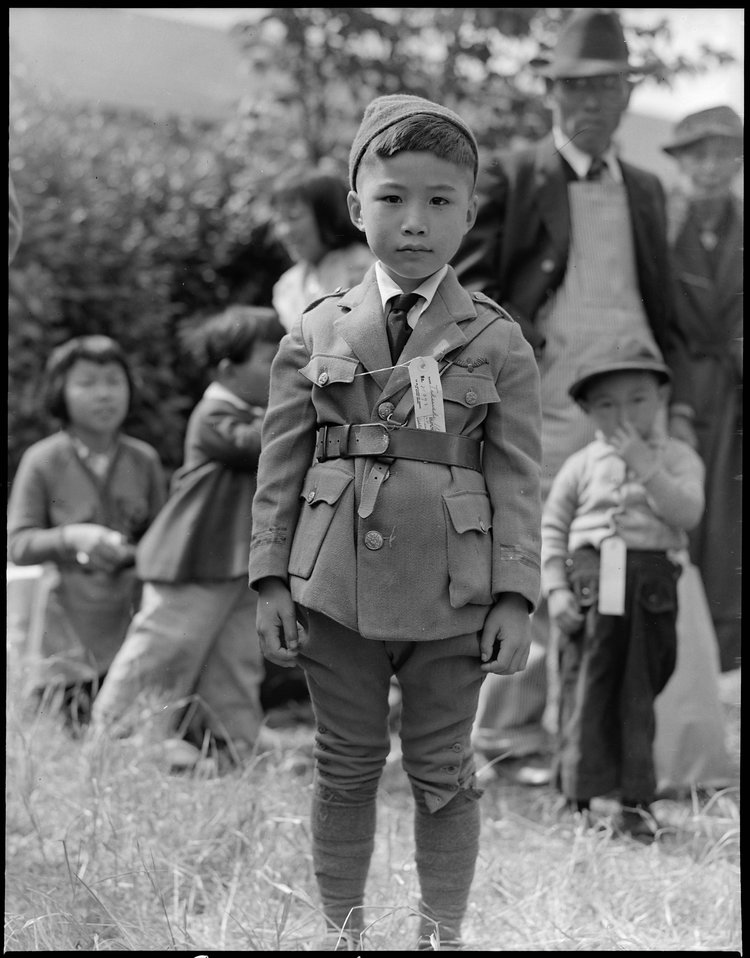

- Byron, California. The bus which will take this farm family of Japanese ancestry to the Assembly center is almost ready to leave. Note identification tag on small boy.

- Centerville, California. This evacuee stands by her baggage as she waits for evacuation bus. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

- San Bruno, California. A Greyhound bus bringing evacuees to the assembly center.

- Oakland, California. This family of Japanese ancestry, is waiting at the Wartime Civil Control Administration station for the bus which will take them and other evacuees to the Tanforan Assembly center under Civilian Exclusion Order Number 28.

- San Bruno, Caliofnira. These older evacuees of Japanese ancestry have just been registered and are resting before being assigned to their living quarters in the barracks. The large tag worn by the woman on the right indicates special consideration for aged or infirm.

- Oakland, California. Part of family unit of Japanese ancestry leave Wartime Civil Control Administration station on afternoon of evacuation, under Civilian Exclusion Order Number 28. Social worker directs these evacuees to the waiting bus.

- San Francisco, California. The Japanese quarter of San Francisco on the first day of evacuation from this area. About 660 merchants, shop-keepers, tradespeople, professional people left their homes on this morning for the Civil Control Station, from which they were dispatched by bus to the Tanforan Assembly center. This photograph shows a family about to get on a bus. The little boy in the new cowboy hat is having his identification tag checked by an official before boarding.

- Oakland, California. Residents of Japanese ancestry waiting for evacuation buses which will take them to the Tanforan Assembly center under Civilian Exclusion Order Number 28.

- Turlock, California. These young evacuees of Japanese ancestry are awaiting their turn for baggage inspection at this Assembly center.

Turlock, California. These young evacuees of Japanese ancestry are awaiting their turn for baggage inspection at this Assembly center.

Byron, California. Field laborers of Japanese ancestry from a large delta ranch have assembled at Wartime Civil Control Administration station to receive instructions for evacuation which is to be effective in three days under Civilian Exclusion Order Number 24. They are arguing together about whether or not they should return to the ranch to work for the remaining five days or whether they shall spend that time on their personal affairs.

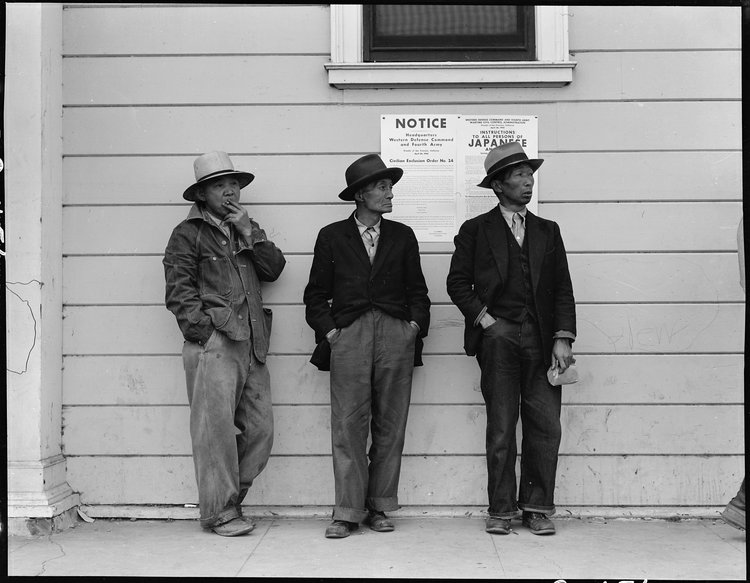

Byron, California. Field laborers of Japanese ancestry in front of Wartime Civil Control Administration station where they have come for instructions and assistance in regard to their evacuation due in three days under Civilian Exclusion Order Number 24. This order affects 850 persons in this area. The men are now waiting for the truck which will take them, with the rest of the field crew, back to the large-scale delta ranch.

“A Caucasian farmer representing a company was trying to get his workers to continue working in the asparagus fields until Saturday when they were scheduled to leave. The workers wanted to quit tonight in order to have time to get cleaned up, wash their clothes, etc.”

— Dorothea Lange

![Sacramento, California. Harvey Akio Itano, 21, 1942 graduate from the University of California where he received his Bachelor of Science [in] Chemistry degree. He was chosen by the faculty as University Medalist for 1942 and was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and Sigma Xi. Mr. Itano went to the Assembly center prior to the commencement exercises at which President Robert Gordon Sproul said, "He cannot be here with us today. His country has called him elsewhere". Mr. Itano hopes to enter the field of medicine and has taken his books with him to the Center where he is spending the duration.](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/17.jpg)

Sacramento, California. Harvey Akio Itano, 21, 1942 graduate from the University of California where he received his Bachelor of Science [in] Chemistry degree. He was chosen by the faculty as University Medalist for 1942 and was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and Sigma Xi. Mr. Itano went to the Assembly center prior to the commencement exercises at which President Robert Gordon Sproul said, “He cannot be here with us today. His country has called him elsewhere”. Mr. Itano hopes to enter the field of medicine and has taken his books with him to the Center where he is spending the duration.

“The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on American soil, possessed of American citizenship, have be come ‘Americanized,’ the racial strains are undiluted.

…It, therefore, follows that along the vital Pacific Coast over 112,000 potential enemies, of Japanese extraction, are at large today. There are indications that these are organized and ready for concerted action at a favorable opportunity.

The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken.”

— General John L. DeWitt, head of the U.S. Army’s Western Defense Command

“What arrangements and plans have been made relative to concentration camps in the Hawaiian Islands for dangerous or undesirable aliens or citizens in the event of national emergency?”

— Franklin D. Roosevelt, President of the United States, August 10, 1936 in a note to the military Joint Board

“Go ahead and do anything you think necessary… if it involves citizens, we will take care of them too. He [the President] says there will probably be some repercussions, but it has got to be dictated by military necessity, but as he puts it, ‘Be as reasonable as you can.’”

— Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, summarizing instructions from President Franklin D. Roosevelt given February 11, 1942

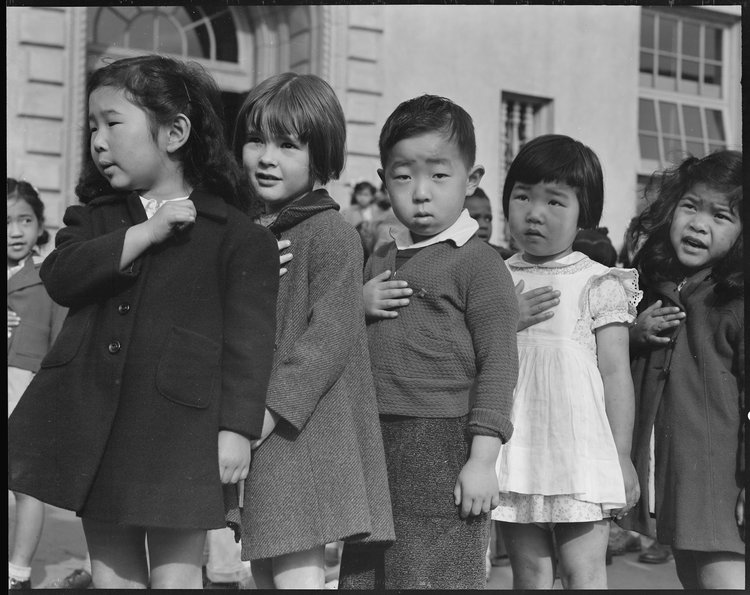

San Francisco, California. Many children of Japanese ancestry attended Raphael Weill public School, Geary and Buchanan Streets, prior to evacuation. This scene shows first- graders during flag pledge ceremony. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration. Provision will be effected for the continuance of education.

San Francisco, California. Flag of allegiance pledge at Raphael Weill Public School, Geary and Buchanan Streets. Children in families of Japanese ancestry were evacuated with their parents and will be housed for the duration in War Relocation Authority centers where facilities will be provided for them to continue their education.

“It is said, and no doubt with considerable truth, that every Japanese in the United States who can read and write is a member of the Japanese intelligence system.”

— FBI Report

“A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched—so a Japanese-American, born of Japanese parents—grows up to be a Japanese, not an American.”

— Los Angeles Times, February 2, 1942

Centerville, California. This youngster is awaiting evacuation bus. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

San Francisco, California. A young evacuee looks out the window of bus before it starts for Tanforan Assembly center. Evacuees will be transferred to War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

“We were herded onto the train just like cattle and swine. I do not recall much conversation between the Japanese.… I cannot speak for others, but I myself felt resigned to do whatever we were told. I think the Japanese left in a very quiet mood, for we were powerless. We had to do what the government ordered.”

— Misuyo Nakamura, Santa Anita Assembly Center, Los Angeles, & Jerome Relocation Center, Arkansas

Woodland, Yolo County, California. Ten cars of evacuees of Japanese ancestry are now aboard and the doors are closed. Their Caucasian friends and the staff of the Wartime Civil Control Administration stations are watching the departure from the platform. Evacuees are leaving their homes and ranches, in a rich agricultural district, bound for Merced Assembly Center about 125 miles away.

Woodland, California. Families of Japanese ancestry with their baggage at railroad station awaiting the arrival of special train which will take them to the Merced Assembly center, 125 miles away.

Woodland, California. This staff of Wartime Civil Control Administration workers have completed their job and stand on the platform awaiting the departure of the special train which has been loaded with evacuees of Japanese ancestry bound for the Merced Assembly center, 125 miles away.

“Although we were not informed of our destination, it was rumored that we were heading for Missoula, Montana. There were many leaders of the Japanese community aboard our train.… The view outside was blocked by shades on the windows, and we were watched constantly by sentries with bayoneted rifles who stood on either end of the coach. The door to the lavatory was kept open in order to prevent our escape or suicide.… There were fears that we were being taken to be executed.”

— Yoshiaki Fukuda, Konko church minister in San Francisco, apprehended December 7, 1941

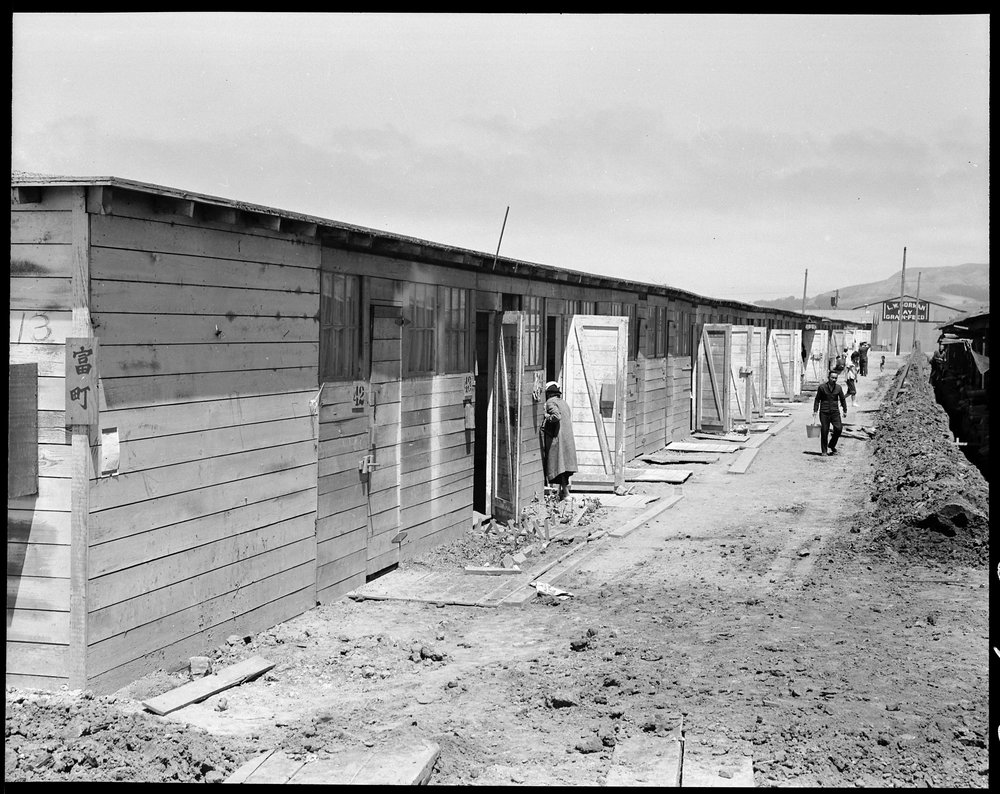

San Bruno, California. This assembly center has been open for two days. Bus-load after bus-load of evacuated persons of Japanese ancestry are arriving on this day after going through the necessary procedures, they are guided to the quarters assigned to them in the barracks. Only one mess hall was operating today. Photograph shows line-up of newly arrived evacuees outside this mess hall at noon. Note barracks in background, just built, for family units. There are three types of quarters in the center of post office. The wide road which runs diagonally across the photograph is the former racetrack.

Stockton, California. Young mother of Japanese ancestry has just arrived at this Assembly center with her baby and she is the last to leave the bus. Her identification number is being checked and she will then be directed to her place in the barracks after preliminary medical examination.

“We went to the stable, Tanforan Assembly Center. It was terrible. The Government moved the horses out and put us in. The stable stunk awfully. I felt miserable but I couldn’t do anything. It was like a prison, guards on duty all the time, and there was barbed wire all around us. We really worried about our future. I just gave up.”

— Osuke Takizawa, Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno

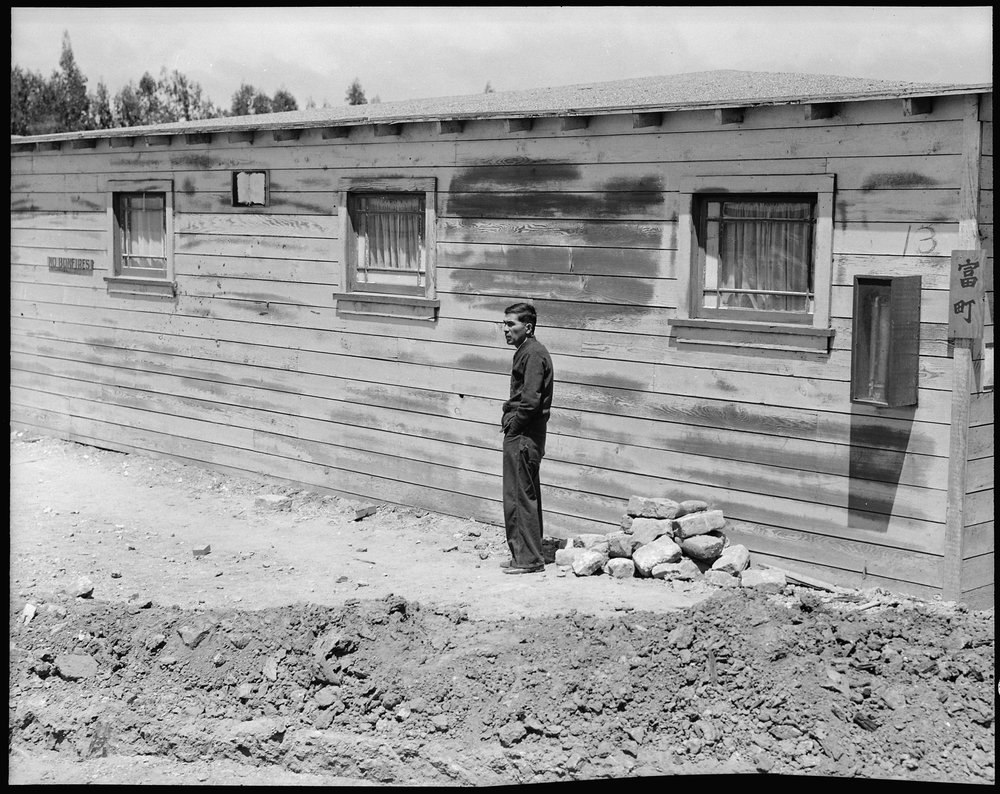

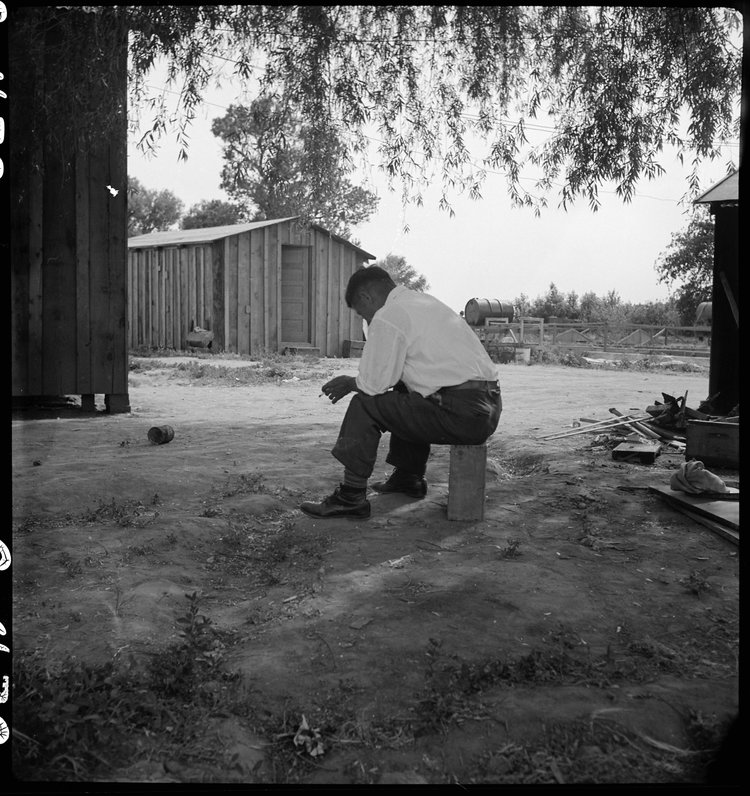

San Bruno, California. Many evacuees suffer from lack of their accustomed activity. The attitude of the man shown in this photograph is typical of the residents in assembly centers, and because there is not much to do and not enough work available, they mill around, they visit, they stroll and they linger to while away the hours.

“We walked in and dropped our things inside the entrance. The place was in semidarkness; light barely came through the dirty window on the other side of the entrance.… The rear room had housed the horse and the front room the fodder. Both rooms showed signs of a hurried whitewashing. Spider webs, horse hair, and hay had been whitewashed with the walls. Huge spikes and nails stuck out all over the walls. A two-inch layer of dust covered the floor.… We heard someone crying in the next stall.”

— Mine Okubo, Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno

San Bruno, California. This scene shows one type of barracks for family use. These were formerly the stalls for race horses. Each family is assigned to two small rooms, the inner one, of which, has no outside door nor window. The center has been in operation about six weeks and 8,000 persons of Japanese ancestry are now assembled here.

“When we got to Manzanar, it was getting dark and we were given numbers first. We went down to the mess hall, and I remember the first meal we were given in those tin plates and tin cups. It was canned wieners and canned spinach. It was all the food we had, and then after finishing that we were taken to our barracks.It was dark and trenches were here and there. You’d fall in and get up and finally got to the barracks.

The floors were boarded, but the were about a quarter to half inch apart, and the next morning you could see the ground below.

The next morning, the first morning in Manzanar, when I woke up and saw what Manzanar looked like, I just cried. And then I saw the mountain, the high Sierra Mountain, just like my native country’s mountain, and I just cried, that’s all.

I couldn’t think about anything.”

— Yuri Tateishi, Manzanar Relocation Center

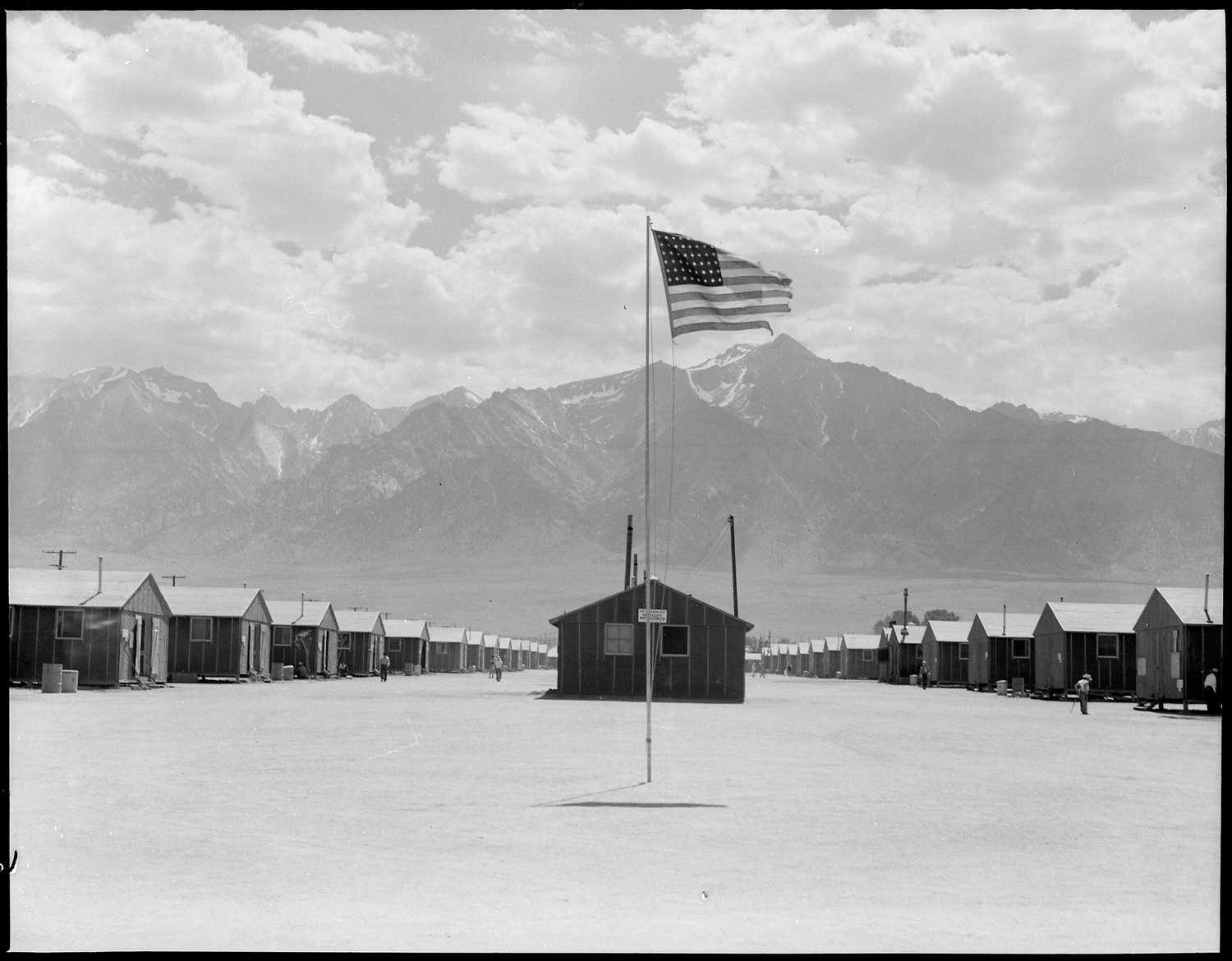

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Street scene of barrack homes at this War Relocation Authority Center. The windstorm has subsided and the dust has settled.

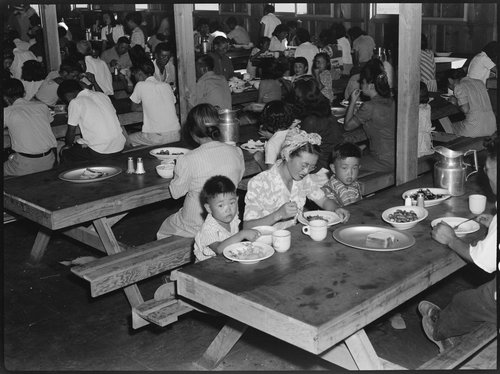

“Good manners eroded as meals were always hurried, reducing the ritual and elegance of Japanese cooking and serving to mere feeding the body. Maintaining personal cleanliness was difficult due to chronic shortage of soap and hot water. Lack of insulation and ventilation made the cubbyholes in which they lived freezing in winter and sweltering in summer. No decent provision for washing diapers. Dust. Mud. Ugliness. Terrible food—definitely not Japanese—doled onto plates from large garbage cans. Nothing to do. Lines for breakfast, lines for lunch, lines for supper, lines for mail, lines for the canteen, lines for laundry tubs, lines for toilets. The most common activity is waiting.”

— Linda Gordon, Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment

San Bruno, California. Supper time! Meal times are the big events of the day within an assembly center. This is a line-up of evacuees waiting for the “B” shift at 5:45 pm. They carry with them their own dishes and cutlery in bags to protect them from the dust. They, themselves, individually wash their own dishes after each meal, since dish washing facilities in the mess halls proved inadequate. Most of the residents prefer this second shift because they sometimes get second helpings, but the groups are rotated each week. There are eighteen mess halls in camp which, together, accomodate 8,000 persons three times a day. All food is prepared and served by evacuees.

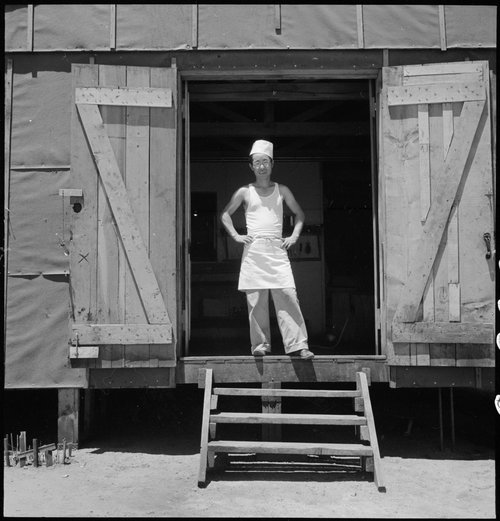

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. A chef of Japanese ancestry at this War Relocation Authority center. Evacuees find opportunities to follow their callings.

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Mealtime in one of the messhalls at this War Relocation Authority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry.

“Each day rolled into weeks and weeks into months and months into years.”

— Ellen Kishiyama, Pomona Assembly Center, Los Angeles & Heart Mountain Relocation Center, Wyoming

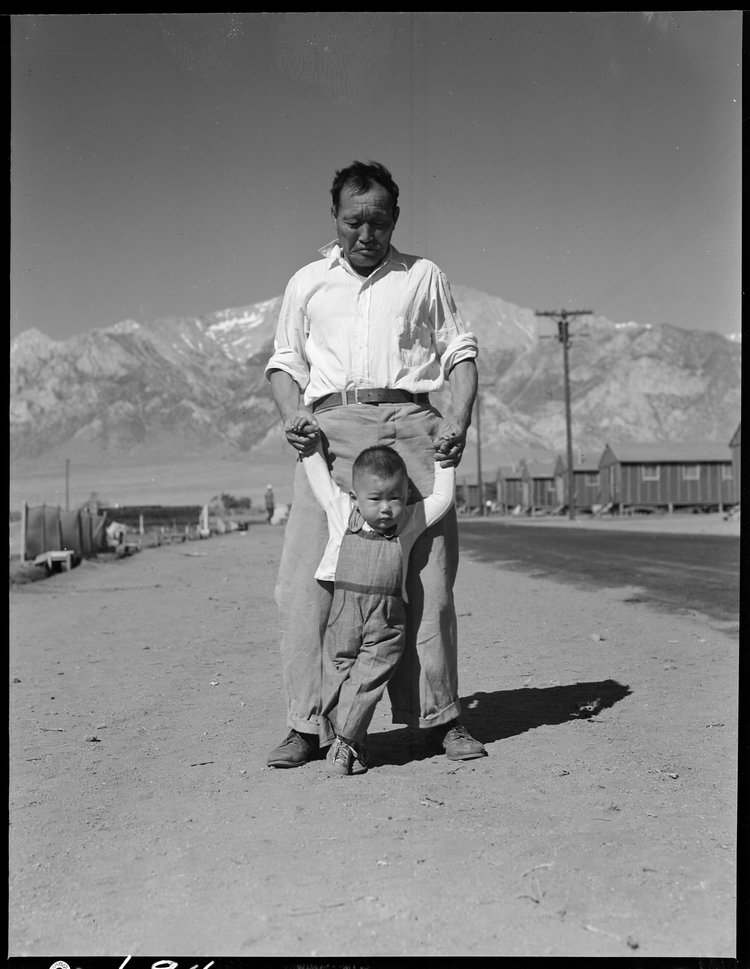

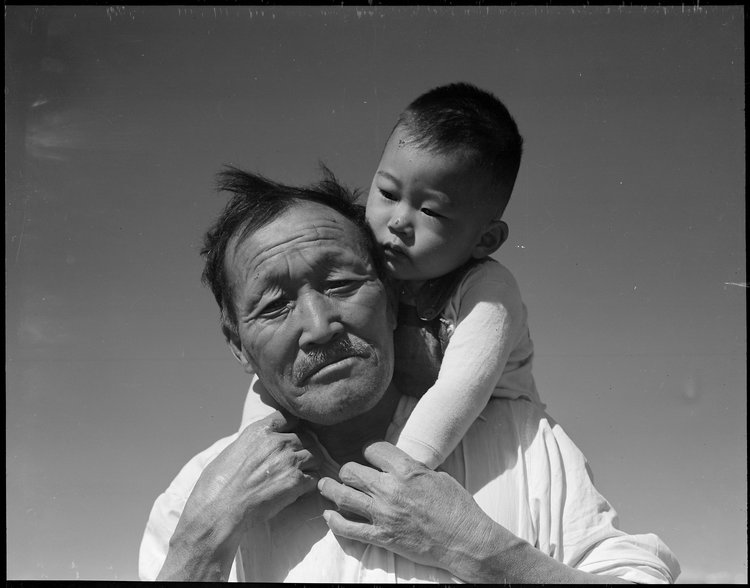

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Grandfather of Japanese ancestry teaching his little grandson to walk at this War Relocation Authority center for evacuees.

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Grandfather and grandson of Japanese ancestry at this War Relocation Authority center.

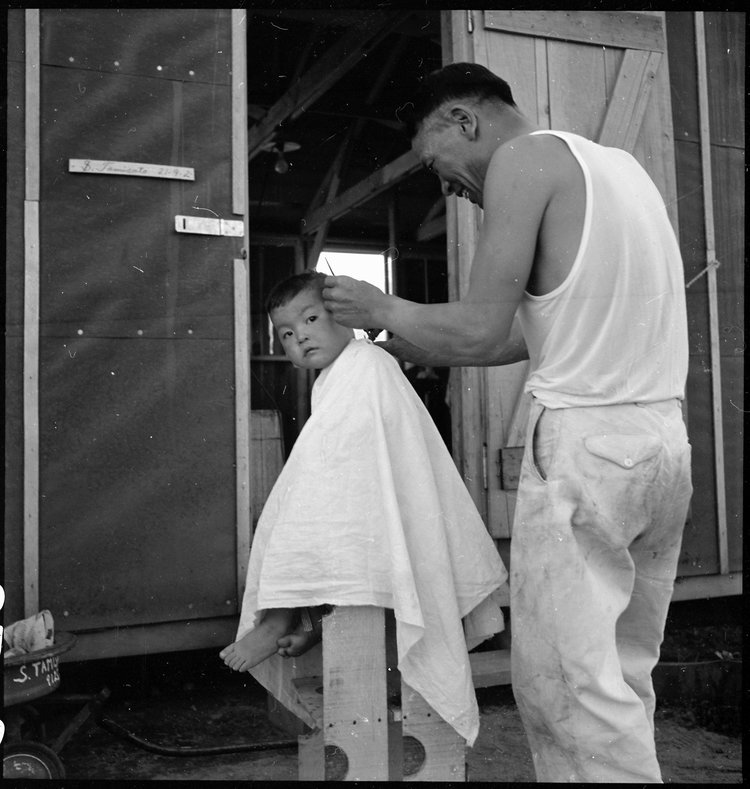

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Little evacuee of Japanese ancestry gets a haircut.

Humor is the only thing that mellows life, shows life as the circus it is. After being uprooted, everything seemed ridiculous, insane, and stupid. There we were in an unfinished camp, with snow and cold. The evacuees helped sheetrock the walls for warmth and built the barbed wire fence to fence themselves in. We had to sing ‘God Bless America’ many times with a flag. Guards all around us with shot guns, you’re not going to walk out. I mean… what could you do? So many crazy things happened in the camp. So the joke and humor I saw in the camp was not in a joyful sense, but ridiculous and insane. It was dealing with people and situations.… I tried to make the best of it, just adapt and adjust.

— Mine Okubo, Tanforan Assembly Center

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Evacuee girls practicing the songs they learned in school prior to evacuation to this War Relocaction Authority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry.

- San Bruno, California. Mrs. Fujita working in her tiny vegetable garden she has planted in front of her barrack home at this assembly center.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Evacuee boy at this War Relocation Authority center reading the Funnies.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. An elementary school with voluntary attendance has been established with volunteer teachers, most of whom are college graduates. These young evacuees are eager to learn and do not mind the lack of equipment.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Little evacuee of Japanese ancestry in a happy mood at this War Relocation Authority center.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Evacuees enjoying the creek which flows along the outer border of this War Relocation Authority center.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Baseball players in a huddle. This game is very popular with 80 teams having been formed to date. Most of the playing is done in the wide firebreak between blocks of barracks.

- San Bruno, California. An art school wall has been established in this Assembly center with large enrollment and a well trained, experienced Japanese staff under the leadership of Professor Chiura Obata of the University of California. This photograph shows a student in Still Life class painting a free water color.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. An elementary school has been established with volunteer evacuee teachers, most of whom are college graduates. Attendance at this time is voluntary. No school equipment is as yet available and available tables and benches are used. Classes are often held outside in the shade of the barrack building.

- San Bruno, California. A barrack building at this assembly center has been reserved for the library which has just been established with a trained librarian of Japanese ancestry in charge. All books and magazines have been donated and the shelves were made from scrap lumber by the evacuees.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Making artificial flowers in the Art School at this War Relocation Authority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. A typical interior scene in one of the barrack apartments at this center. Note the cloth partition which lends a small amount of privacy.

“It was a terribly hot place to live. It was so hot that when we put our hands on the beadstead, the paint would come off! To relieve the pressure of the heat, some people soaked sheets in water and hung them overhead.”

— Hatsumi Nishimoto, Pinedale Assembly Center, Fresno

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. A view of surrounding country flanked by beautiful mountains at this War Relocation Authority center.

“Meanest dust storms… and not a blade of grass. And the springs are so cruel; when those people arrived there they couldn’t keep the tarpaper on the shacks.”

— Dorothea Lange, at Manzanar

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. More land is being cleared of sage brush at the southern end of the project to enlarge this War Relocation Authority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry.

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. William Katsuki, former professional landscape gardener for large estates in Southern California, demonstrates his skill and ingenuity in creating from materials close at hand, a desert garden alongside his home in the barracks at this War Relocation Authority center.

“They got to a point where they said, ‘Okay, we’re going to take you out.’ And it was obvious that he was going before a firing squad with MPs ready with rifles. He was asked if he wanted a cigarette; he said no.… You want a blindfold?… No. They said, ‘Stand up here,’ and they went as far as saying, ‘Ready, aim, fire,’ and pulling the trigger, but the rifles had no bullets. They just went click.”

— Ben Takeshita, recounting his older brother’s ordeal at Tule Lake Relocation Center, where he was segregated for causing trouble

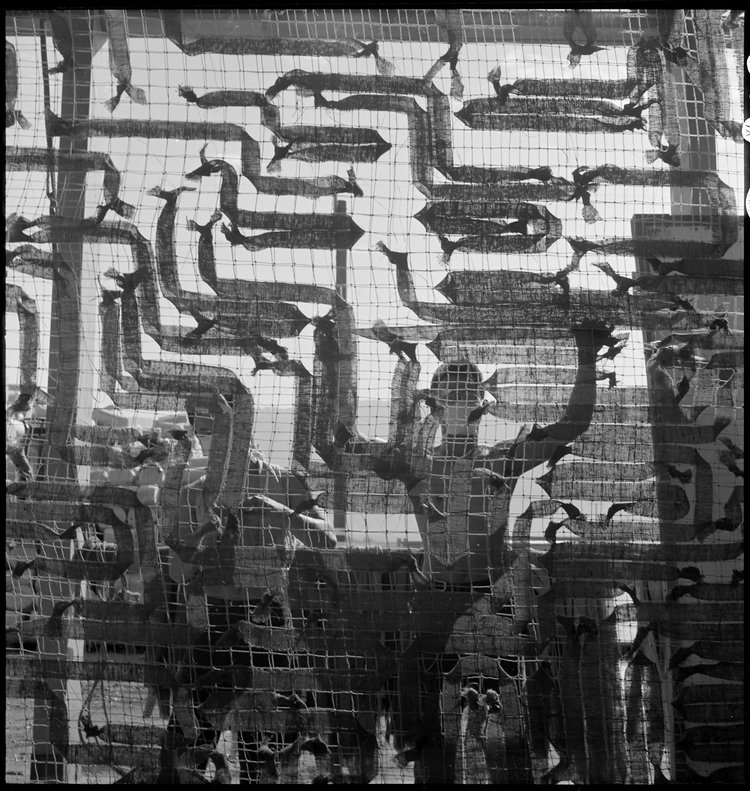

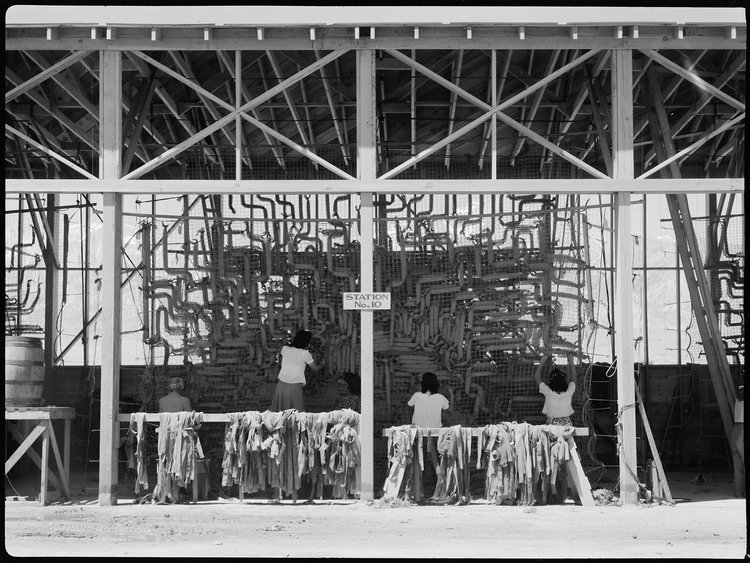

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Making camouflage nets for the War Department. This is one of several War and Navy Department projects carried on by persons of Japanese ancestry in relocation centers.

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Making camouflage nets for the War Department. This is one of several War and Navy Department projects carried on by persons of Japanese ancestry in relocation centers.

At Manzanar and at the Santa Anita Assembly Center near Los Angeles, army engineers supervised manufacture of camouflage nets. Huge weavings of hemp, designed to fit over tanks and other large pieces of war matériel, they were constructed from cords that hung from giant stands; the workers usually wore masks to protect themselves from the hemp dust. The army claimed that they were volunteers but they were in fact coerced by camp administrators, who were receiving requisitions for large numbers of nets from the army. (One of the first strikes at the camps occurred when 800 Santa Anita camouflage-net workers sat down and refused to continue, complaining of too little food. They won some concessions.) At Manzanar other internees worked in a large agricultural project to grow and improve a plant, guayule, that could become a substitute for rubber. With rudimentary and often homemade equipment, chemists and horticulturalists hybridized guayule shrubs to obtain a substance of tensile strength with low production costs. These undertakings were illegal under the Geneva Convention, which forbade using prisoners of war in forced labor, and as a result only American citizens were usually employed so that the army could claim that these were not POWs.

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Guayule beds in the lath house at the Manzanar Relocation Center.

“One Jap became mildly insane and was placed in the Fort Sill Army Hospital. [He]… attempted an escape on May 13, 1942 at 7:30am. He climbed the first fence, ran down the runway between the fencing, one hundred feet and started to climb the second, when he was shot and killed by two shots, one entering the back of his head. The guard had given him several verbal warnings.”

— FBI Report of the death of Ichiro Shimoda, a gardener from Los Angeles who had been taken from his family on December 7, 1941

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Making camouflage nets for the War Department. This is one of several War and Navy Department projects carried on by persons of Japanese ancestry in relocation centers.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Lawns and flowers have been planted by some of the evacuees at their barrack homes at this War Relocation Authority center.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. A view of section of the lath house at this War Relocation Authority center where seedling guayule plants are propagated by experienced evacuee nurserymen in the guayule rubber experiment project.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Hospital latrines, for patients, between the barracks, which serve temporarily as wards. For the first three months of occupancy medical facilities have been meager but the new hospital fully equipped, is almost ready for occupancy.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Evacuees at this War Relocation Authority center relaxing in the shade of their barrack apartment.

- Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. In the lath house of the guyaule rubber experiment project. These seedlings (culls from Salinas) were planted here on May 8 in cut-off paper milk cartons. These milk cartons are being used in place of clay pots, reducing costs to a minimum.

“Without any hearings, without due process of law…, without any charges filed against us, without any evidence of wrongdoing on our part, one hundred and ten thousand innocent people were kicked out of their homes, literally uprooted from where they have lived for the greater part of their lives, and herded like dangerous criminals into concentration camps with barb wire fencing and military police guarding it.”

— A statement by The Fair Play Committee, organized by Kiyoshi Okamoto at Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming, after Secretary of War Stimson announced on January 20, 1944 that nisei, formerly classed as “aliens not acceptable to the armed forces,” would be subject to the draft

The government charged 63 members and seven leaders of The Fair Play Committee with draft evasion and conspiracy to violate the law. The trial judge, Blake Kennedy, addressing the defendants as “you Jap boys,” sentenced the members to three years imprisonment. The seven leaders were sentenced to four years in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary.

“I remember having to stay at the dirty horse stables at Santa Anita. I remember thinking, ‘Am I a human being? Why are we being treated like this?’ Santa Anita stunk like hell.… Sometimes I want to tell this government to go to hell. This government can never repay all the people who suffered. But, this should not be an excuse for token apologies. I hope this country will never forget what happened, and do what it can to make sure that future generations will never forget.”

— Albert Kurihara, Santa Anita Assembly Center, Los Angeles & Poston Relocation Center, Arizona

Woodland, California. Tenant farmer of Japanese ancestry who has just completed settlement of their affairs and everything is packed ready for evacuation on the following morning to an assembly center.

References

- Linda Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro, Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment

- John Armor and Peter Wright, Manzanar: Photographs by Ansel Adams, Commentary by John Hersey

- Densho: Controlling the Historical Record: Photographs of the Japanese American Incarceration

- Jonah Engel Bromwich, New York Times: Trump Camp’s Talk of Registry and Japanese Internment Raises Muslims’ Fears

- Carl Takei, Los Angeles Times: The incarceration of Japanese Americans in World War II does not provide a legal cover for a Muslim registry

- ACLU: A Dark Moment in History: Japanese Internment Camps

- WW2 Japanese Relocation Camp Internee Records

- National Archives: Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority

Read more at: anchoreditions.com

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

Advertisement

Advertisements