Advertisement

At the end of 2011, a company called Isaias 21 Property paid nearly $3 million — in cash — for an oceanfront Bal Harbour condo.

(Article by Nicholas Nehamas, republished from //www.miamiherald.com/news/business/real-estate-news/article69248462.html)

But it wasn’t clear who really owned the three-bedroom unit at the newly built St. Regis, an ultra-luxury high-rise that pampers residents with 24-hour room service and a private butler.

In public records, Isaias 21 listed its headquarters as a Miami Beach law office and its manager as Mateus 5 International Holding, an offshore company registered in the British Virgin Islands, where company owners don’t have to reveal their names.

There the trail ran cold.

Until now.

That’s because the Miami Herald, in association with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, has obtained a massive trove of confidential files from inside a secretive Panamanian law firm called Mossack Fonseca. The leak has been dubbed the “Panama Papers.”

Paulo Octávio resigned as governor of Brasília after being accused of corruption in 2011. He secretly paid $2.95 million for a condo at the St. Regis in Bal Harbour later that year. Mossack Fonseca specializes in creating offshore shell companies for the world’s richest and most powerful people.

Mossack Fonseca specializes in creating offshore shell companies for the world’s richest and most powerful people.

The firm’s leaked records offer a glimpse into the tightly guarded world of high-end South Florida real estate and the global economic forces reshaping Miami’s skyline.

And MF’s activities bolster an argument analysts and law-enforcement officials have long made: Money from people linked to wrongdoing abroad is helping to power the gleaming condo towers rising on South Florida’s waterfront and pushing home prices far beyond what most locals canafford.

The leak comes as the U.S. government unleashes an unprecedented crackdown on money laundering in Miami’s luxury real-estate market.

Buried in the 11.5 million documents? A registry revealing Mateus 5’s true owner: Paulo Octávio Alves Pereira, a Brazilian developer and politician now under indictment for corruption in his home country.

A Miami Herald analysis of the never-before-seen records found 19 foreign nationals creating offshore companies and buying Miami real estate. Of them, eight have been linked to bribery, corruption, embezzlement, tax evasion or other misdeeds in their home countries.

That’s a drop in the ocean of Miami’s luxury market. But Mossack Fonseca is one of many firms that set up offshore companies. And experts say a lack of controls on cash real-estate deals has made Miami a magnet for questionable currency.

“The guys who want to clean up dirty money are always going to try to penetrate the system at its weakest spot,” said Joe Kilmer, a former Drug Enforcement Administration special agent. “You’ve got so much real estate being bought and sold in South Florida. It’s easy to hide in plain sight.”

Take Octávio, a dentist’s son who built a fortune developing shopping malls and hotels in Brazil and married the granddaughter of a former Brazilian president before launching his own political career.

In late 2009, Octávio was serving as the vice governor of the capital state of Brasília when federal police filmed his boss, the governor, accepting a thick stack of bills. Prosecutors said it was a bribe. Other tapes caught their associates stuffing pockets, bags and even their socks with cash. Their alleged total take? About $43 million.

Gov. Jose Roberto Arruda of Brasília (left) was forced to resign when federal police filmed him accepting what they said was a bribe. Several other of Arruda and Octavio’s associates were filmed taking alleged bribes, including Leonardo Prudente, a former state representative shown here stuffing his jacket (top right) and socks (bottom right) with cash. When Gov. Jose Roberto Arruda was arrested early the next year, Octávio replaced him. But an informant claimed Octávio also took bribes. The newly minted governor didn’t appear in the videos and denied the allegations, but he resigned anyway. His term lasted 12 days.

When Gov. Jose Roberto Arruda was arrested early the next year, Octávio replaced him. But an informant claimed Octávio also took bribes. The newly minted governor didn’t appear in the videos and denied the allegations, but he resigned anyway. His term lasted 12 days.

Six months later, Octávio’s Miami lawyer asked Mossack Fonseca — which has recently been implicated in a bombshell Brazilian corruption scandal — to set up Mateus 5.

‘Funny money’

In Miami, secretive buyers often purchase expensive homes using opaque legal entities such as offshore companies, trusts and limited liability corporations.

Offshore companies are legal as long as the companies declare their assets and pay taxes. But the secrecy that surrounds those companies makes it easy and tempting to break the law.

The U.S. Treasury Department is so concerned about criminals laundering dirty money through Miami-Dade County real estate that in March it started tracking the kind of transaction most vulnerable to manipulation: shell companies buying homes for at least $1 million using cash.

Those deals are considered suspicious because a) the real buyers can hide behind shell companies and b) banks aren’t involved in cash transactions, circumventing any checks for money laundering.

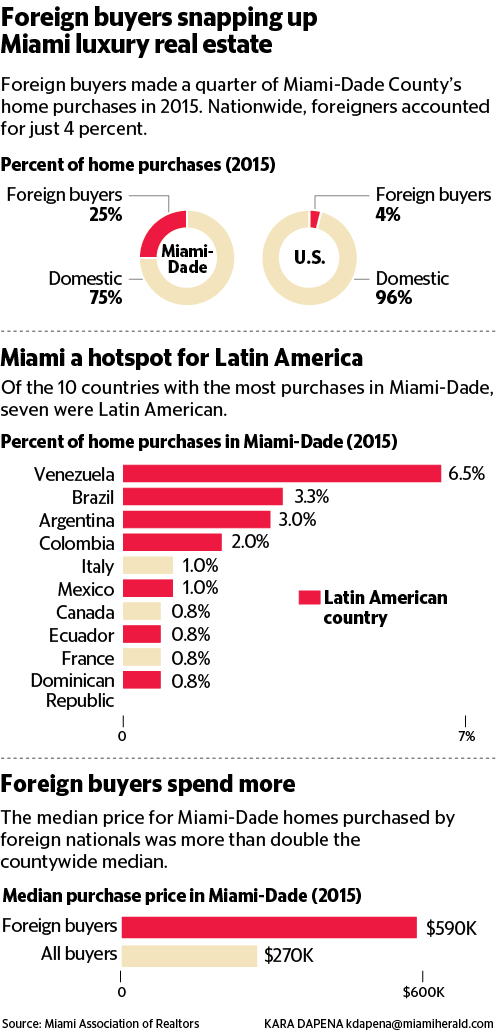

Cash deals accounted for 53 percent of all Miami-Dade home sales in 2015 — double the national average — and 90 percent of new construction sales, according to the Miami Association of Realtors.

“A property owned in the name of a shell company is not transparent,” said Jennifer Shasky Calvery, director of the U.S. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCen), the Treasury agency behind the new policy. “There may be legitimate reasons to be non-transparent, but it’s also what criminals want to do.”

The temporary initiative also applies to Manhattan and expires in August. It requires that real-estate title agents identify the true, or “beneficial,” owners behind shell companies and disclose their names to the federal government. In Miami-Dade, the rules apply to homes sold for $1 million or more. In Manhattan, where real estate is more expensive and where foreign buyers also flock, the threshold is $3 million.

No other jurisdictions are being targeted.

The feds will know the real buyers but won’t make the information public. Experts say the crackdown could be the first in a series of stronger regulations on cash deals.

Miami has a long history of money laundering. Its financial institutions report more suspicious activity than any other major U.S. city besides New York City and Los Angeles, according to FinCen data. And a recent case of money laundering involving fancy condos and the violent Spanish drug gang Los Miami drew further scrutiny to South Florida.

Jack McCabe, an analyst who studies the booming local housing market, said it’s impossible to know how many homes are purchased with dirty money.

“But I think many people believe it could be a sizable portion of the new condominium market in Miami,” McCabe said. “Even though developers and real-estate professionals suspect many of these units are bought with illegal funds, they realize their projects may not be successful without that support.”

NO ONE WANTS TO KILL THE GOOSE THAT LAID THE GOLDEN EGG. Jack McCabe, analyst

Flight capital from other countries fuels Miami’s economy. It revived the construction, real-estate and tourism industries after the Great Recession.

Foreign nationals bought nearly $6.1 billion worth of homes in Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties last year, more than a third of all local home spending, according to the Miami Association of Realtors. It’s not only foreign money that’s suspect. Mauricio Cohen Assor and Leon Cohen-Levy, a Miami Beach father-and-son duo convicted of a $49 million tax fraud in 2011, used Mossack Fonseca offshores to hide assets.

“No one wants to kill the goose that laid the golden egg,” McCabe said.

Law firms like Mossack Fonseca and their Miami partners operate in a shadow economy, largely free from the “know-your-customer” rules imposed on U.S. banks. Others in the real-estate industry, including Realtors, are also exempt.

The corrupt know they can park their cash here with few questions asked.

In Brazil, prosecutors claim Mossack Fonseca created offshore companies that allowed officials of the state oil company to collect and hide bribes. At a news conference in January 2016, prosecutors called the firm “a big money launderer” and announced they had issued arrest warrants for four employees of its Brazilian office for crimes ranging from money laundering to destroying and hiding documents.

In an email, Mossack Fonseca spokesman Carlos Sousa defended its business practices: “Our firm, like many firms, provides worldwide registered agent services for our professional clients (e.g., lawyers, banks, and trusts) who are intermediaries. As a registered agent we merely help incorporate companies, and before we agree to work with a client in any way, we conduct a thorough due-diligence process, one that in every case meets and quite often exceeds all relevant local rules, regulations and standards to which we and others are bound.”

Mossack Fonseca also said that its Brazilian office was a franchise, and that the Panama law firm, which practices only in Panama, “is being erroneously implicated in issues for which it has no responsibility.”

You can read MF’s full response on MiamiHerald.com.

From Brasília to Bal Harbour

Paulo Octávio was indicted on corruption charges a year after stepping down as governor. He did not respond to a request for comment. But his local lawyer Julio Barbosa, who keeps an office on pricey Lincoln Road and asked Mossack Fonseca to set up the offshore, said the purchase of the Bal Harbour condo violated no laws.

“Any transactions in South Florida handled by my firm complied with all applicable laws, including U.S. and Brazilian taxation and disclosure requirements,” Barbosa wrote in an email to the Miami Herald.

Owning U.S. property through offshore companies is popular with foreign nationals because it allows them to claim significant breaks on their estate taxes, thanks to the U.S tax code. But offshores are also useful for shifting money around beyond the reach of regulators and tax authorities — not to mention estranged spouses and angry creditors.

Routing money through a web of offshores and other entities can help add a patina of legitimacy to dirty cash, said Ellen Zimiles, a former federal prosecutor in New York. That’s crucial for bringing tainted money from abroad into the United States without raising suspicion, Zimiles said.

I LOVE MIAMI AND THE UNITED STATES, SO I CHOSE TO INVEST HERE. Marcos Pereira Lombardi

Many of the people named as owning offshore companies belong to Brazil’s upper echelon, which has pumped money into Miami real estate as the Brazilian economy has collapsed.

Other people in the files include:

▪ Helder Rodrigues Zebral, the former owner of a popular Brazilian steakhouse convicted twice for embezzling public funds and avoiding public bidding in his home country. Known for driving a Mercedes and dating socialites, Zebral paid $1.9 million for a condo in Sunny Isles Beach in 2011, between his two trials.

▪ Marcelo Carvalho Cordeiro, the former president of Rio de Janeiro’s pension fund, who wasfired after allegedly handing out a multimillion-dollar contract through improper back channels. Cordeiro paid $2.7 million for a home on Key Biscayne last year. He is suing a business partner in Miami for libel.

▪ Luciano Lobao, a construction magnate and the son of Brazil’s former energy minister. The elder Lobao is under investigation for corruption in a massive scandal over alleged bribes for state oil company contracts.

Lobao himself has been investigated over allegations he overcharged the government on 2014 World Cup contracts. He bought a condo at Eden House in Miami Beach for $636,000 in 2013 and sold it for $1.1 million the next year.

There’s no proof that dirty money was used in any of the transactions uncovered by the Herald.

Several of the men, including Lobao and Cordeiro, made no effort to hide the deals. They set up BVI offshores and then bought the properties using Florida companies registered under their own names. Emails between Mossack Fonseca employees and the men’s lawyers say the purpose of the offshores was to purchase Florida real estate but don’t go into detail.

The Miami Herald called, emailed or sent registered letters to the buyers, as well as their lawyers, asking what role the offshore companies played in the transactions or whether their assets were declared to Brazilian tax authorities, as required by law. Two of them responded.

Marcelo Calvo Galindo is a top executive at a Brazilian network of universities that is facing criminal charges for tax evasion in Brazil. He paid $2.7 million for two units — one of them a 2,900-square-foot penthouse — at the St. Tropez in Sunny Isles Beach. He showed the Miami Herald tax returns stating that he had paid taxes for his offshore companies in Brazil.

Marcos Pereira Lombardi, who runs a newspaper, as well as several other businesses in Brasília, said he set up an offshore for estate-tax benefits. He spent $2.7 million on two condos at Trump Towers I and II in Sunny Isles Beach and said he pays all his taxes in Brazil and the United States.

“I bought these properties in Miami because it was a business opportunity, as prices in Florida were very attractive,” he wrote in an email. “I love Miami and the United States, so I chose to invest here.”

Lombardi, known as “Marcola,” has been investigated in Brazil for allegedly getting an insider deal on government land and conspiring to fix gas prices, charges he denies. He bought one Trump Tower unit through a Florida company that listed him as its manager and another under his own name.

But transparency doesn’t always mean legality.

The alleged Spanish drug lord Alvaro López Tardón owned fancy condos in Miami through companies registered under his own name or the names of his associates, including a $1 million condo at the Continuum in South Beach.

After his arrest in 2011, López Tardón’s lawyers defended his actions as legal and transparent

Convicted money launderer Alvaro López Tardón bought a $1 million condo at the Continuum in South Beach. A federal judge in Miami sentenced the accused Spanish drug lord to 150 years in prison for money laundering. His case is on appeal. The judge said South Florida is awash in “funny money.” CHUCK FADELY Miami Herald file Prosecutors argued that he was laundering profits from a lucrative cocaine-smuggling business. They said he had been the leader of a violent drug ring called Los Miami and seized his assets, including a fleet of luxury cars and 13 condos, after he was found guilty of money laundering.

.

Prosecutors argued that he was laundering profits from a lucrative cocaine-smuggling business. They said he had been the leader of a violent drug ring called Los Miami andseized his assets, including a fleet of luxury cars and 13 condos, after he was found guilty of money laundering.

Peter Zalewski, a local condo market analyst, said López Tardón’s case prompted the feds to take a hard look at Miami real estate.

“Locally, people have been talking about illicit money propping up the condo market since the 1980s,” Zalewski said. “The government usually needs a catalyst like this before it can act.”

A Miami federal judge sentenced López Tardón to 150 years in prison.

“I call it funny money, and we have a plethora of funny money here,” U.S. District Judge Joan Lenard said during his sentencing hearing in 2014.

A cleaned-up game?

“Funny money” includes more than briefcases brimming with hundred-dollar bills, a common sight during Miami’s cocaine cowboy era in the 1980s. Today, “cash” more commonly signifies certified checks, traveler’s checks, cashier’s checks and money orders.

For now, FinCen is tracking only transactions that use cash in those forms, as well as hard currency. It will not require reporting on deals that use wire transfers or personal checks, which leave more of a paper trail at banks, opening up a potential loophole.

By not monitoring those financial instruments, investigators will miss out on most sales of new condos, said Alan Lips, a Miami accountant.

Theresa Van Vliet, a former federal prosecutor in South Florida, said FinCen could have been uncomfortable stretching its authority to cover wire transfers.

“This is a strategic move,” she said. “It’s good to start small.”

Cash home deals are one of the last unregulated sectors of the U.S. real-estate market; there are already strict reporting requirements for homes bought with mortgages.

Despite the federal scrutiny, most industry professionals say money laundering doesn’t play a role in real estate — at least not anymore.

“When I was selling real estate in Davie in the late ’80s, we used to get bags of cash,” said Jeff Morr, a Realtor at Douglas Elliman. “There were no rules. … Today, everything is watched. It’s clean.”

Developer David Martin, who is closing sales for a 319-home development in Doral, said the new FinCen rules haven’t caused a single buyer to back out.

“I think this is really blown out of proportion,” agreed Carlos Rosso, president of the condo division for local mega-developer Related Group. “Everything is done through the banking system for new construction. Maybe for [single-family] homes and existing condos they are

Dirty or not, the surge of foreign money means big changes for people who livehere.

The real-estate boom that kicked off in 2011 spawned construction jobs and tax dollars. City boosters touted the foreign investment as a sign that Miami had arrived on the world stage. But the boom also sent home prices soaring beyond the reach of many working- and middle-class families. Locals trying to buy homes with mortgages can’t compete with foreign buyers flush with cash and willing to pay the list price or more.

Two-thirds of Miamians now rent their homes — more than any other major city in the United States — and that number is up eight percentage points since 2006, according to a recent study from New York University. High housing costs have combined with low incomes to make Miami the least affordable city for renters in the country.

“If we’re stifling people’s ability to create a financial asset like a home, we’re stopping their ability to start new businesses [and] to invest in education for their families,” said Ali Bustamante, a researcher at Florida International University.

Feds are watching

In 2001, the USA Patriot Act mandated that all parties involved in real-estate closings perform due diligence on their clients. Lobbying from the industry won it a temporary exemption that has been in place for nearly 15 years.

Real-estate agents argue they don’t have the expertise to investigate their clients.

The American Bar Association has also opposed stronger disclosure requirements for real-estate lawyers, saying they would violate attorney-client privilege.

But the new federal initiative centering on Miami-Dade and Manhattan may be the first sign that the exemption is ending.

“This is the ceremonial first pitch,” said Miami lawyer Andrew Ittleman said. “We still haven’t gotten into the game.”

Between the federal crackdown on secret cash home deals and strengthening anti-money-laundering rules around the world, it may grow harder to pump dirty cash through Miami real estate.

Other countries have stricter rules than the United States.

The European Union has started building a centralized database of beneficial owners. The EU’s compliance rules extend to real-estate agents, law firms and trust agents, as well as financial institutions.

That disparity frustrates some American bankers, who say they bear too much of the burden in the United States.

“It would be a lot easier for a bank like us to do our job if others [in the real-estate industry] had similar responsibilities,” said Scott Nathan, an executive vice president at Miami Lakes-based Bank United.

A number of events and blog posts have explored loopholes in the new FinCen rules.

One local seminar held in March was headlined “How to Avoid the Treasury Trap.” It promised to teach real-estate professionals “how to avoid money-laundering charges and stay on the right side of the law” while working with clients who want to keep their deals secret for legitimate reasons.

“You can not only survive, you can thrive,” an advertisement said.

The Miami Association of Realtors hosted the event.

Teresa King Kinney, the association’s CEO, said the intention was not to dodge the regulations. “It was to make sure our members understand what the rules are, how they can affect a deal and what the alternatives are,” Kinney explained.

Jennifer Shasky Calvery, FinCen’s director, disagreed. She compared the industry’s behavior to a drunk driver turning around before reaching a roadside DUI checkpoint.

“It’s always amazing that the drivers think the police aren’t watching that,” Calvery said. “I feel like we’re really learning about the culture of the real-estate economy in Miami.”

Read more at: //www.miamiherald.com/news/business/real-estate-news/article69248462.html

Submit a correction >>

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

Advertisement

Advertisements