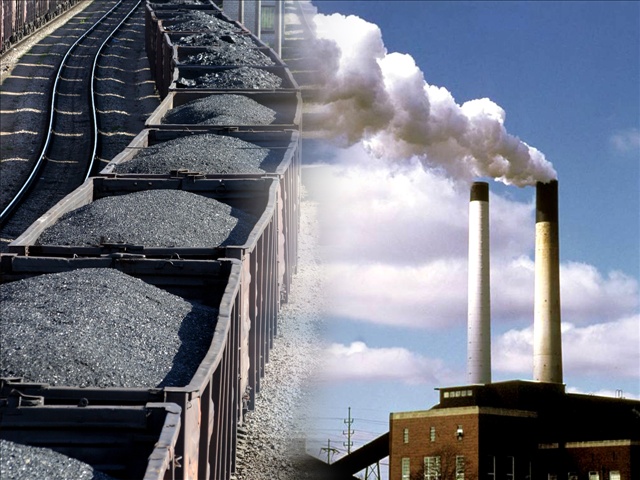

In a stunning move just days before the New Year, the Department of Energy (DOE) commanded three coal-fired units in Indiana, totaling more than 950 megawatts, to ignore their planned retirement dates and keep generating electricity. This decision is not an isolated incident but a cornerstone of a deliberate and contentious shift in national energy strategy, one that prioritizes immediate grid reliability over environmental virtue signaling.

Key points:

- The U.S. Department of Energy issued 90-day emergency orders on December 23, forcing three Indiana coal units to operate past their December 31 retirement dates.

- The agency cites tightening electricity supply and surging demand in the Mid-continent grid region as justification, warning of a potential emergency.

- This action is part of a broader pattern of last-minute federal interventions to halt coal plant retirements in multiple states, affecting over 3.1 gigawatts of capacity.

- Ratepayer advocates warn the move will increase electricity bills, while environmental groups are challenging similar orders in federal court.

- The policy aligns with a larger administration push, backed by substantial funding, to revitalize coal infrastructure for grid stability and industrial growth.

The heart of story lies in the quiet towns of Wheatfield and Warrick County, Indiana. There, the Energy Department’s December 23 directive landed like a late-hour script change for utilities Northern Indiana Public Service Co. (NIPSCO) and CenterPoint Energy. The utilities had prepared to shutter NIPSCO’s two units at the Schahfer station and CenterPoint’s F.B. Culley Unit 2, moves reviewed and approved by the regional grid manager, the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO). The final curtain was set for December 31. The DOE’s order, issued under Section 202(c) of the Federal Power Act, commands a three-month encore, at minimum, arguing that portions of MISO face a genuine emergency due to rising power demand and a shrinking supply cushion.

The emergency authority and a growing pattern

This legal tool is meant for true crises, a fire alarm to be pulled only when the lights are genuinely at risk of flickering out. The DOE now contends that the collective retirement of aging power plants, coupled with what Energy Secretary Chris Wright has called the “surging electricity demand” of “reindustrialization and winning the AI race,” has created a persistent vulnerability. The Indiana orders are merely the latest in a string of such interventions. In recent months, the agency has invoked the same authority to keep coal plants running in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Washington. Together, these actions have forced about 3.1 gigawatts of aging fossil fuel capacity—enough to power millions of homes—to remain online.

For the utilities caught in the middle, the order creates a complex dilemma. They must now reverse course, sourcing coal, staffing operations, and maintaining equipment they had deemed financially and operationally obsolete. The costs of this sudden about-face will not be borne by the companies alone. A recent ruling by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission allows these added operating costs to be absorbed by the entire regional grid, meaning millions of consumers could see a line item on future bills funding this extended performance.

Ben Inskeep of the Citizens Action Coalition of Indiana speaks plainly to the local impact, stating, “The federal government’s order to force extremely expensive and unreliable coal units to stay open will result in higher bills for Hoosiers who are already reeling from record-high rate increases in 2025.”

Will the reinstatement of coal powered plants eventually reduce costs, or will all the extra energy be consumed by upcoming AI data centers, as consumer energy needs are de-prioritized?

A clash of visions for the grid’s future

The DOE’s stance sets up a fundamental clash between two visions of reliability. One view, held by the administration and supporters of the policy, sees the massive, always-on power of baseload coal plants as an irreplaceable bedrock. They argue that the transition to natural gas and renewables has moved too quickly, leaving the grid fragile. The other perspective, held by the utilities that planned these retirements, environmental groups, and some state officials, sees forced reliance on aging, often inefficient coal plants as a costly and regressive step. They argue it stifles investment in newer, cleaner technologies and ignores market signals and long-term planning. This legal and philosophical battle is already in the courts, where a coalition including the attorneys general of Michigan, Minnesota, and Illinois, alongside groups like the Sierra Club, is challenging the DOE’s earlier orders for a Michigan plant, arguing the agency has failed to prove a true emergency exists.

Historically, the American power grid’s evolution has been a slow but steady march from coal dominance toward a more diversified mix including natural gas, wind, and solar. The current administration’s actions represent a conscious pivot, an attempt to rewind that tape. It is a policy backed by financial muscle, including a $625 million allocation announced earlier in the year with hundreds of millions specifically earmarked to recommission and retrofit coal units. The goal, as stated, is to “prolong the operational life spans of aging coal plants” in the name of reliability. The Indiana orders are the on-the-ground implementation of that top-down strategy, a test case of whether federal authority can effectively mandate a fuel source in a restructured electricity market.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.