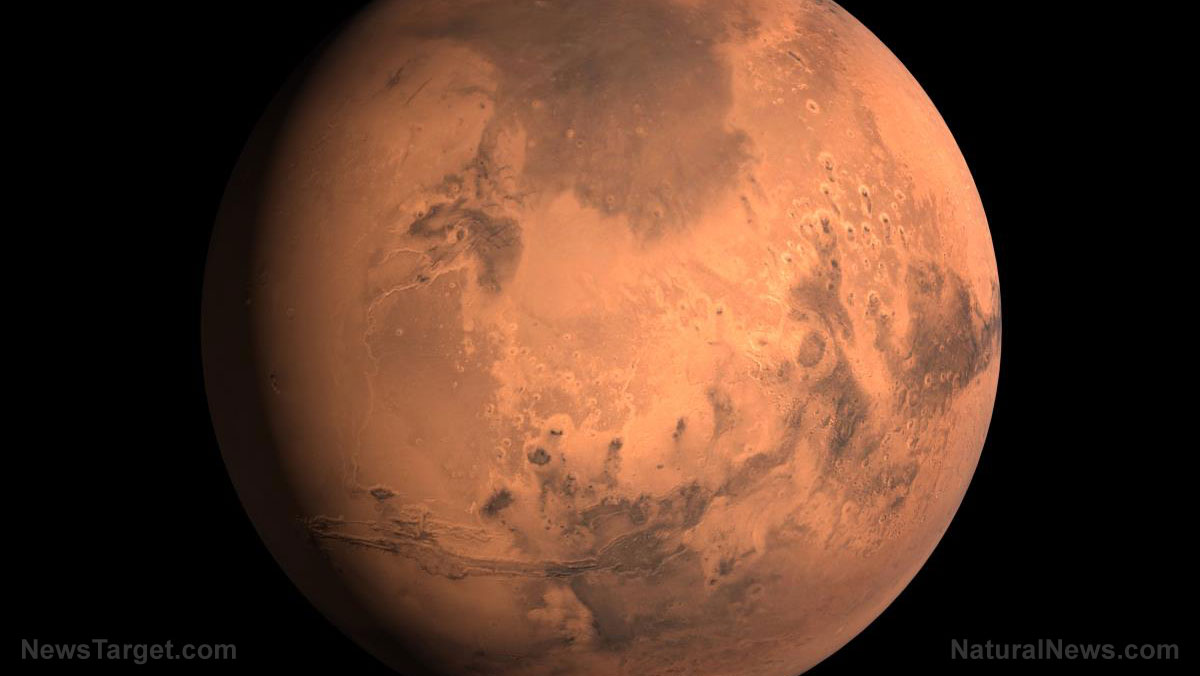

As it turns out, the universe may be much younger than previously thought.

This is according to researchers at the Max Planck Institute in Germany who, in a study published in the journal Science, claim that the universe is actually a couple of billion years younger than what scientists originally believed.

This reduction in the universe’s age is the result of calculations using a new Hubble constant -- a figure that is commonly used to describe the expansion rate of the universe, as observed in the movement of the stars.

Considered to be one of the most important numbers in cosmology, the Hubble constant is normally set at 70, which results in the universe getting a general age of 13.7 billion years. However, upon changing the constant to 82.4, the team, led by post-doctoral researcher Inh Jee, arrived at a figure of 11.4 billion.

According to Jee, they changed the Hubble constant to account for gravitational lensing, a phenomenon first proposed by physicist Albert Einstein in his theory of general relativity. (Related: Space-time ripples could help scientists uncover exoplanets from other galaxies.)

Understanding gravitational lensing

Gravitational lensing, according to physicists, is a phenomenon in which the gravitational field of a large object in space -- like a star or a planet, for instance -- bends incoming light. Because large celestial bodies like planets have strong gravitational fields that extend into space, incoming light from stars can get refracted at a large distance, thereby distorting large regions of space.

As noted in the study, Jee’s team used a specific variety of gravitational lensing known as time delay lensing to compute the new Hubble constant.

Time delay lensing uses the changing brightness of distant objects to gather information for their calculations. Jee’s theory regarding the age of the universe is the latest entry in a long-running astronomical debate that started many years ago.

In 2013, a European team came up with a Hubble constant number of 67 after looking at leftover radiation from the Big Bang. Earlier this year, a group of NASA scientists led by Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist Adam Riess of the Space Telescope Science Institute came up with a constant of 74. The Max Planck team’s newest calculation, however, is noticeably larger than any other estimate.

Jee admits, however, that her team's number comes with a major caveat: It came from using only two gravitational lenses since those were all that were available.

This, Jee said, meant that her team's margin of error is large enough to allow the universe to actually be older than what they had calculated.

The Max Planck team said that future researchers must observe more lensing systems in order to narrow down the value of the Hubble constant. Doing so will allow them to determine a more accurate age for the universe.

Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb, who wasn’t part of the study, agrees, noting that the large error margins in Jee’s study limit its effectiveness, comparing it to using a ruler without fully understanding how it works.

For more news about the universe, visit Space.news.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.