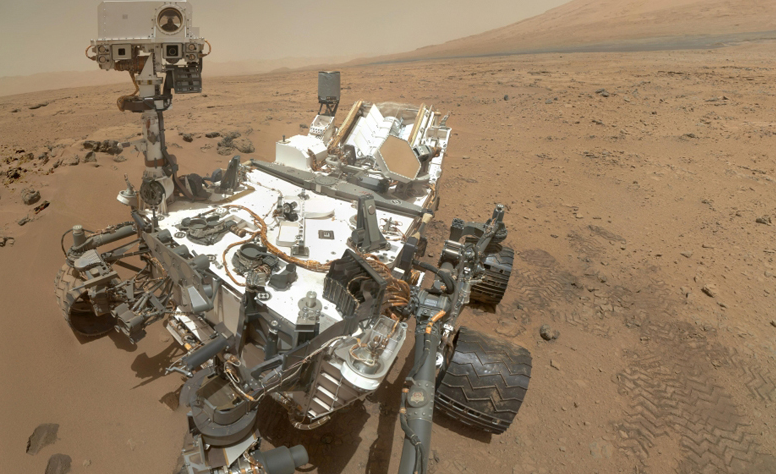

European researchers are raising the possibility that the Milky Way galaxy is teeming with rocky planets that harbor continents and massive oceans like Earth. In a paper published this February in the journal Science Advances, the researchers discussed how rocky planets might have formed from small water-bearing dust particles that could give rise to the formation of oceans and continents.

How water emerges on planets

Scientists are still trying to figure out how water emerged on Earth. One of the prominent theories points to water-bearing comets or icy asteroids that slammed the planet in its infancy.

But the researchers are calling that theory into question, positing that water has been present since a planet's birth. This is true not only for Earth but also for Venus, Mars and many other rocky planets in the galaxy.

"All our data suggest that water was part of Earth's building blocks, right from the beginning. And because the water molecule is frequently occurring, there is a reasonable probability that it applies to all planets in the Milky Way," explained Anders Johansen, a professor of planetary science at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and the lead researcher of the study.

Johansen and his team used a computer model to determine how rocky planets formed. Their model indicated that millimeter-sized dust particles containing ice and carbon accreted 4.5 billion years ago to form what would later become Earth.

"Up to the point where Earth had grown to one percent of its current mass, our planet grew by capturing masses of pebbles filled with ice and carbon. Earth then grew faster and faster until, after five million years, it became as large as we know it today," Johansen said.

Over time, surface temperatures rose sharply, according to Johansen, causing the ice in the pebbles to turn to gas.

Other rocky planets in the Milky Way might have also formed via "pebble accretion" as water molecules are found everywhere in the galaxy. With optimal temperatures, according to Johansen, these planets started out with the same amount of water and carbon as Earth and probably continue to harbor the same amount of water to this day.

Alien life in the Milky Way?

The team's model also suggests that other planets in the Milky Way share a similar land size as Earth, according to Martin Bizzarro, Johansen's colleague at the University of Copenhagen and one of the study researchers. This, according to Bizzaro, should provide good opportunities for the emergence of life.

But if the amount of water that formed were random, then planets would look vastly different. Some would be too dry while others covered completely by water. These extreme environments, in turn, could not possibly give birth to complex life forms.

"A planet covered by water would, of course, be good for maritime beings but would offer less than ideal conditions for the formation of civilizations that can observe the universe," Johansen explained. (Related: Researchers discover 45 potentially habitable exoplanets.)

The researchers are looking forward to the next generation of space telescopes, which will offer far better opportunities to observe planets outside the solar system. According to Johansen, these telescopes could help scientists tell how much water is present on a planet.

Last year, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration detected an Earth-size planet using one of its newest space telescopes, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). Located more than 100 light-years away, the planet orbits its star's habitable zone, the orbital region around a star where conditions are just right to allow the existence of liquid water on the surface.

Read more fascinating studies about space at Cosmic.news.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.