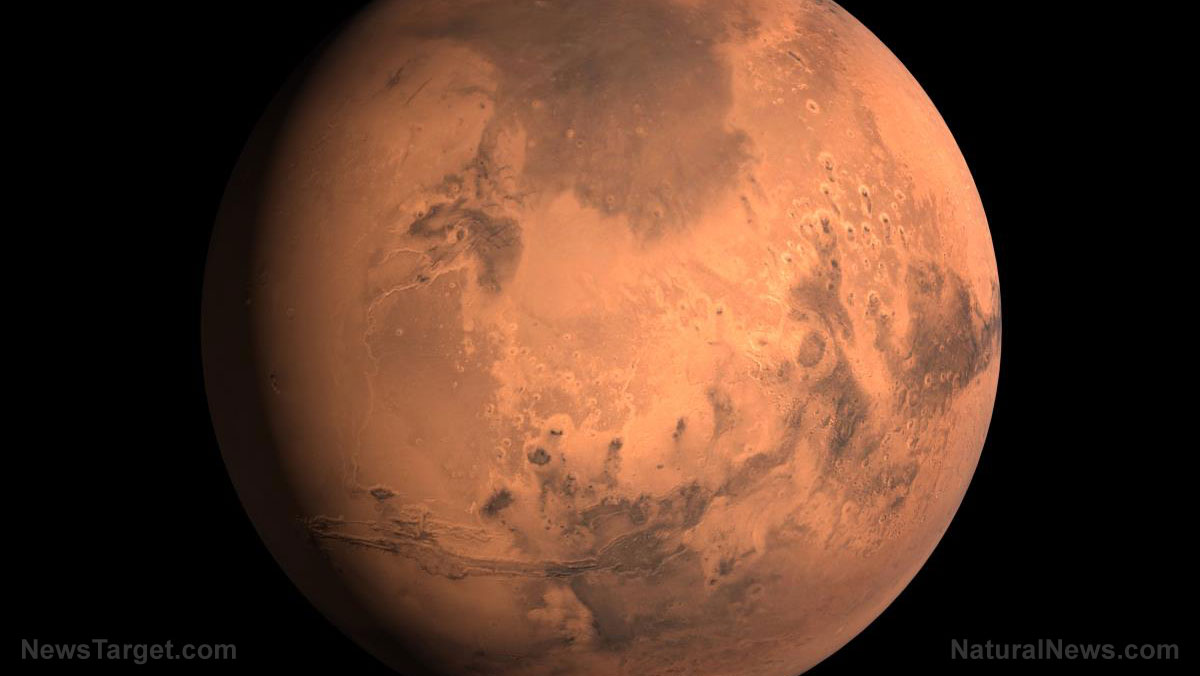

On the surface, Mars seems very quiet. It has no active volcanoes, and the only water it harbors is locked up underground and on the polar caps. But as it turns out, this placid-looking planet hosts landslides called "slumps" from time to time.

While scientists have known about these slumps for at least a decade, the mechanisms behind them had been unclear. Now, a team of researchers has found that small-scale melting ice beneath the surface may be causing landslides on the Red Planet.

In a new study published in the journal Science Advances, the researchers described how the interaction between underground water ice and salts within Mars-like soil triggers a chemical reaction that creates unstable icy slush that weakens the soil.

Exploring the science behind Martian landslides

In the last decade, scientists have captured images of slumps using the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's High-Resolution Imaging Experiment aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. These landslides are usually accompanied by a trail of dark, narrow lines called recurring slope lineae (RSLs).

Little is known about RSLs. A handful of observations indicate that these lines are always sun-facing, appear most commonly near the equator and occur seasonally, typically when temperatures are higher than usual on Mars. But aside from these, scientists don't know much about RSLs because no rover or lander has been near one to capture images of them up close. As it is, their exact cause had been unknown.

Past studies link RSLs to the interaction of chlorine salts and large amounts of sulfates (another type of salt). Mars analog investigations showed that when salts interact with gypsum (a sulfate mineral) or water underground, they cause disruptions on the surface such as sinkholes and landslides.

For their experiment, the researchers added another element to the mix, permafrost or frozen ground. The equatorial regions of the Red Planet are assumed to harbor permafrost with small ice grains surrounding soil and mineral particles.

The researchers mixed sulfates, chlorine salts and ice particles with volcanic ash obtained from Mars-like places on Earth: the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica, the Dead Sea in Israel and the Salar de Pajonales in the Atacama Desert. The mixture was frozen then gradually thawed at Martian temperatures.

An unstable slush consisting of frozen and liquid brine formed at a temperature of -58 degrees, followed by the gradual melting of ice at -20 to -4 degrees. The salts then migrated upward toward the surface and dried out, in turn collapsing and disrupting the soil.

"I was thrilled to observe such rapid reactions of water with sulfate and chlorine salts in our lab experiments and the resulting collapse and upheave of Mars analog soil on a small scale," said Janet Bishop, a senior scientist at the SETI Institute in California and the lead researcher of the study.

Dust storms may be triggering landslides on Mars

The researchers noted that warmer temperatures of around -58 degrees to -20 degrees can support small-scale briny water during the Martian spring and summer beneath the equatorial surface.

If this subsurface brine expands and contracts over time, it could weaken the soil and create a fragile crust with cavities. When a dust storm happens, accumulated dust on the crust could lead to "slumping" of surface material and tumbling of particles downslope, leaving RSL tracks that mark locations of former salt crusts.

"Most of us Mars scientists have considered modern Mars as a cold and dry and dormant place, shaped mostly by dust storms," Bishop said. "If our hypothesis is correct, then RSL could be indicators for salts on Mars and for near-surface active chemistry."

The study could point to the possibility that the Red Planet was once habitable. Some hardy creatures have been found in briny waters several hundred feet below the McMurdo Dry Valleys.

While the icy slush is currently too salty to harbor life, it's possible that the environment just below the surface was habitable much longer than the Martian surface was. (Related: Scientists say the best place for life on Mars is underground.)

"It is difficult to estimate how long, but perhaps [habitable] liquid water was present around soil grains below the surface until three or two billion years ago or even more recently," said Bishop.

Read more fascinating studies about Mars at Space.news.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.