Researchers from the Lulea University of Technology in Sweden have discovered 45 distant planets that may be capable of hosting life. In a study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A, the researchers said that these exoplanets may possess Earth-like atmospheres and may be able to maintain stable liquid water.

With several active and planned sky surveys, the researchers said that their findings could be used to refine exoplanet searches.

45 Exoplanets possess Earth-like characteristics

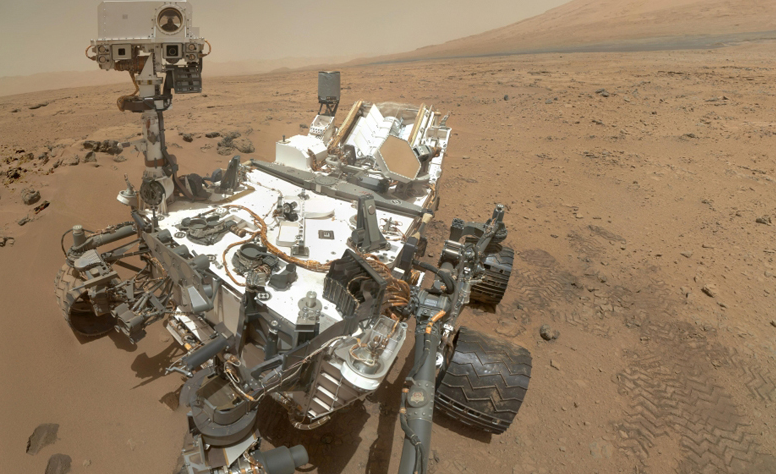

Detecting habitable exoplanets is not easy; scientists can’t just send a probe to distant stars using current spacefaring technologies. For instance, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Juno probe reaches speeds of up to 165,000 miles per hour. At those speeds, Juno would take about 17,157 years to reach Proxima Centauri b, the nearest exoplanet with a potentially habitable atmosphere.

Instead, scientists have to pour through data gathered from telescopes and sensors here on Earth and in orbit to learn more about these exoplanets.

For their study, the researchers combed through existing exoplanet catalogs in search of distant worlds known to have hydrogen, oxygen, dinitrogen and carbon dioxide in their atmospheres. The researchers estimated how fast those four “atmospheric species” escape into space using the “kinetic theory of gases” (how gases move about the atmosphere).

The team found 17 exoplanets in one catalog that met their habitability criteria and another 28 exoplanets on the wider exoplanet list. These worlds, according to the researchers, can potentially retain gases essential to life in their atmospheres and may be able to maintain stable liquid water.

“We conclude that, based on our current knowledge of the detected exoplanets, 45 of them are good candidates for habitability studies,” wrote the researchers.

The researchers recommend revisiting the current definition of a star's habitable zone, the orbital region around a star where planets could have stable atmospheres to support liquid water. The team explained that the capacity of a planet to host an Earth-like atmosphere should be added to the required conditions for habitability. (Related: Astronomers unveil first direct image of young exoplanet just 63 light-years away.)

“The discrimination of exoplanets based on the gas species that they can retain in their atmospheres will help determine the most probable candidates for potential habitability,” said the researchers.

In addition, the model used for the study, according to the team, can be used by active and planned exoplanet survey missions to detect gases of interest. For instance, scientists working on NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite mission can use the model to look for the most promising exoplanets.

24 “Superhabitable” exoplanets discovered

In another study, published in the journal Astrobiology, American and German researchers identified 24 exoplanets that may be more habitable than Earth. These “superhabitable” exoplanets, according to the researchers, may possess characteristics that are more suitable for sustaining life for a longer period of time.

Two of these characteristics are the exoplanet’s size and mass. The researchers said that if a planet is 10 percent larger and 1.5 times more massive than Earth, that planet would have more surface area to live on and its interior would retain more heat from radioactive decay. The implication of the latter is that the interior, which is responsible for a planet’s magnetic field, would remain active longer and therefore sustain the atmosphere for a longer time.

In addition, if a planet is eight degrees warmer and had more water than Earth, the biodiversity on the planet would likely be more robust. Life forms would also be more complex if a planet orbits a K-type dwarf star, which is cooler and less massive than the sun.

K-type dwarf stars have a lifespan of up to 70 billion years, giving life forms a much longer time to emerge and develop.

While none of the 24 exoplanets met all of the criteria, the researchers said that each exoplanet possessed at least one of those characteristics. With several active and planned exoplanet surveys, these two studies can help improve efforts to detect signs of alien life.

Cosmic.news has more on the search for life on other planets.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.