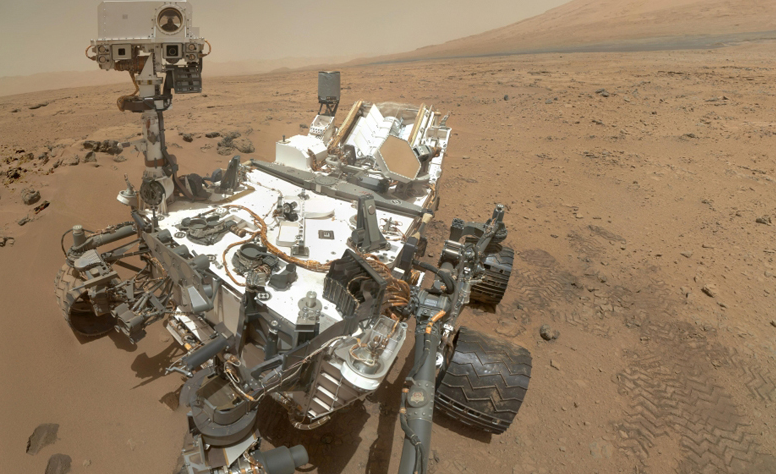

Researchers looking for evidence that solar wind formed lines of blob-like shapes finally stumbled across the distinctly-shaped phenomena in space probe data taken more than 40 years ago.

In 1974 and 1976, Germany and NASA launched the Helios space probes into orbit around the sun. The two spacecraft took readings of the solar wind and particles for years.

Decades later, researchers from the University of L'Aquila went over the data sent back by Helios. Imagine their confusion when they came across perfect wave patterns instead of the irregular ones they expected.

Simone Di Matteo led the efforts to eliminate the too-good-to-be-true patterns. Finally, they saw the trains of solar particle blobs coming from the sun on an average cycle of 90 minutes.

Di Matteo and his teammates think that these blobs may explain the origins of the solar wind. The process that generates solar activity may leave clues on the blobs.

Their study supports NASA's Parker Solar Probe mission. Launched in 2018, Parker follows in the path of the Helios spacecraft. While waiting for the data from the probe, researchers from around the world practiced with earlier data. (Related: 4 Tips for avoiding skin cancer when you’re NOT in the sun.)

The Helios space probes ran into solar wind blobs during the 1970s

The 93 million miles between the sun and the Earth make it hard for researchers to observe the solar wind. Density, temperature, and other vital information will have vanished by the time the wind reaches the planet.

In response, the researchers turned to Helios data for answers. The two probes came within 30 million miles of the sun.

They began by following the spacecraft's readings of the blobs to their starting point on the sun. Then they compared the 1970s data to modern magnetic maps of the star's surface. The results let them identify the regions on the sun that might produce blobs of the solar wind.

Next, Di Matteo looked for specific patterns of changing waves as the solar wind blobs flowed across the Helios probe. When the readings turned out to be too clean and precise, he suspected that something was wrong with the instrumentation aboard the old spacecraft.

Study saved by the internet, which unearthed the plans for the solar probe

Since the original Helios operators were long retired or dead, Di Matteo browsed the internet for any publicly available data on the space probe's sensors. He found a German-language instruction manual that revealed the spacecraft carried two different instruments for measuring the solar wind.

Furthermore, Helios regularly alternated between the instruments because its designers did not know at the time which sensor worked better. The regular switch between sensors created the false readings.

Once the researchers got rid of the erroneous data taken by Helios whenever it switched between instruments, they found that the probe encountered solar wind blobs on five occasions. For the first time, they got highly-detailed data on the formations within 30 million miles of the sun.

The researchers reported that the blobs proved denser and hotter than ordinary solar winds. However, they were unable to determine if the sun released a series of such blobs every 90 minutes or so on a continuous basis, or in random spurts. They also didn't know how much each individual blob varied.

Answers may come from the Parker Solar Probe. The new spacecraft will come within 15 million miles of the sun during its flybys.

Like Helios, Parker may end up flying into solar wind blobs. Its closer heliocentric orbit makes it possible that the space probe might catch a freshly formed blob as the formation rises from the surface of the sun.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.