The typical visual depiction of the Earth's mantle as a solid band of yellow-orange sitting between the crust and core has just received an update. A recent paper in Nature Geoscience now describes it as “more heterogenous” than what people previously thought.

An international group led by the University of Utah provided a more diverse representation of the mantle, far different compared to the lava that reaches the surface.

“If you look at a painting from Jackson Pollock, you have a lot of different colors,” explained lead author Sarah Lambart, a geology professor at the University of Utah. “Those colors represent different mantle components and the lines are magmas produced by these components and transported to the surface.”

Mid-ocean ranges provide researchers with the best access to the mantle. These seafloor mountain systems erupt lava from the mantle to produce new ocean crust.

While an analysis of the lava would show that it is similar to others found on Earth, what happens to crustal rock after its life cycle is something different. Old oceanic crust moves away from mid-oceanic ridges until it reaches a continent, where it goes under it and back into the mantle. (Related: Mantle mystery: Geologists don’t know what to make of two continent-sized mountains found beneath the Earth’s crust.)

The oldest rocks in lava hold clues about the Earth's mantle

Lambert's team worked to find out the mantle's appearance before it moves up and becomes lava at a mid-ocean ridge. They investigated cumulate minerals, the first material that forms crystals when the magma goes into the crust.

The researchers checked the most primitive part of the cumulate minerals. Upon finding them, the team evaluated the rocks' chemical composition.

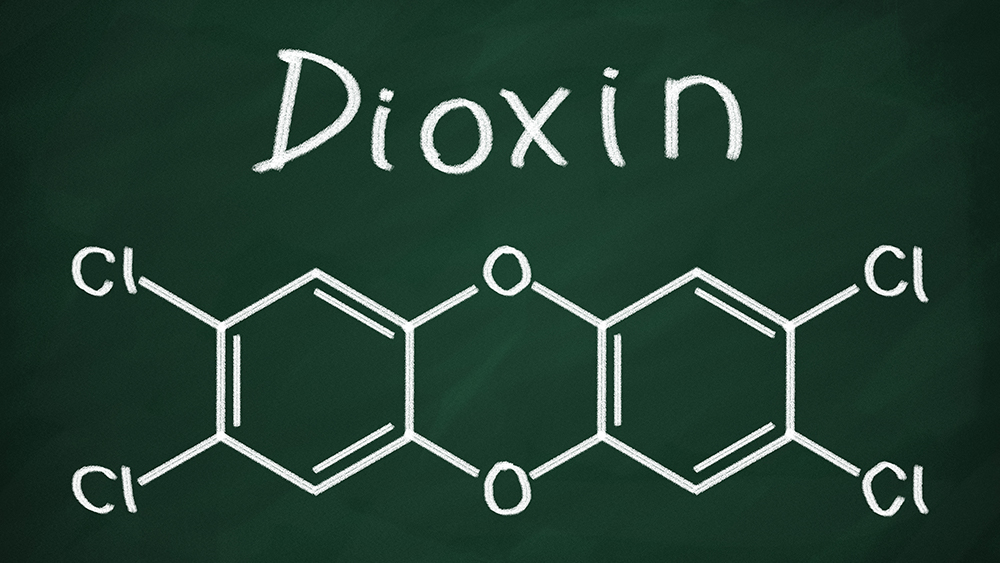

If both the mantle and the old crust melt, the magma will have some differences in their chemical composition.

Lambart said that the evidence of the first melt appeared in the most primitive part of the lava — the cumulate minerals. They evaluated changes in the isotopes of neodymium and strontium. If the isotope levels shifted, then the mantle also had “isotopic variability.”

The researchers found that the isotopic variability in the cumulate minerals was seven times greater than the levels in the mid-ocean ridge lava. Thus, the mantle that produced the cumulates shared the same variability found in primitive rocks.

Lambart explained that different rocks have different melting points. For example, old crust melts faster than other materials.

The first rock to melt might make channels that would haul magma from the mantle to the crust above. A similar effect might take place when another type of rock melted later.

Eventually, the various molten rocks created several channel networks. All of the channels headed toward the mid-ocean ridge, but they didn't intermingle with the others.

The Earth "blends" magma from the mantle as the molten rock goes up

It helps to imagine the Earth's mantle as a blender filled with various ingredients for making a smoothie. Think of a blender carafe with fruit, ice, milk, and other foodstuffs.

Like the carafe, the mantle comprises different materials. Each mineral stands out and doesn't mix with the others.

Going back to the blender example, activating the blending process turns the ingredients into a smoothie. The blended foods become much less distinct and intermix — much like the lava at mid-ocean ridges.

Lambart believed that the Earth triggered its blending process between the deep mantle and the mid-ocean ridge. Her team's results indicated that it took place somewhere in the crust.

“The problem is we need to find a way to model the geodynamic earth, including plate tectonics, to actually reproduce what is recorded in the rock today,” Lambart explained. “So far this link is missing.”

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.