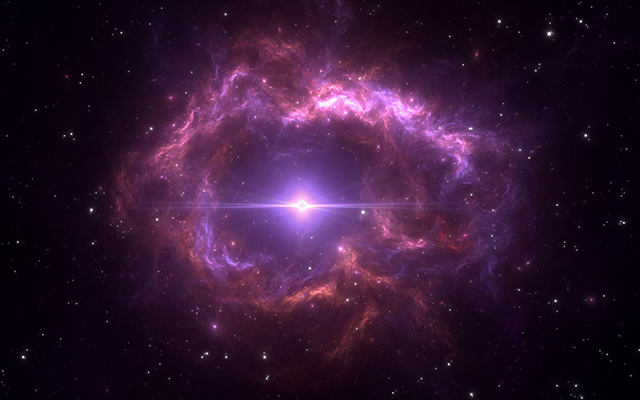

There is a star found 250 light-years from our solar system. Although much smaller and dimmer than the sun, it is currently undergoing an explosion of electromagnetic radiation that might create simple lifeforms on any nearby exoplanets.

Called ULAS J224940.13-011236.9, it is one of the coolest and smallest stars known to exist in the universe. Usually, the star doesn't appear on ordinary telescopes and instruments – that's how dim it is.

However, it recently started releasing a white-light superflare, an abrupt discharge of electromagnetic energy that dwarfs the typical solar flare in magnitude and output.

A superflare releases so many high-energy particles. The white-light version is rarer and even more energetic – it makes the emitting star look brighter and whiter than it usually is.

Researchers from the University of Warwick spotted ULAS J224940.13-011236.9 as it released the superflare. Their calculations indicated that the magnetic explosion was 10 times stronger than the largest solar flares released by the sun.

The energy released by the superflare measured around 80 billion megatons of TNT explosive. In comparison, the most destructive nuclear weapon created by man only produced around 50 megatons of energy. (Related: Scientists bewildered by “mysterious crystals” found in the core of giant alien planets.)

Tiny star gets the stellar equivalent of 15 minutes of fame

Despite its astonishingly bright and massive superflare, the star itself was small, even for stellar standards. Its diameter measured only 10 percent of the sun's diameter, making it roughly the same size as Jupiter.

Besides its small diameter, ULAS J224940.13-011236.9 was also a literal lightweight. It belongs to a class of mass objects that just barely achieves the minimum mass required for classification as a full-fledged star.

L dwarf stars like ULAS J224940.13-011236.9 fill the gap between standard stars and brown dwarfs. In turn, brown dwarfs are substellar mass objects that are too small, cool, and dull to count as stars.

Saying an L dwarf star is brighter than a brown dwarf doesn't count for much. Most telescopes fail to spot them from the background light cast by nearby neighbors that emit far more light in typical circumstances.

The Warwick researchers weren't looking for ULAS J224940.13-011236.9 in the first place. They were surveying the stars around the L dwarf star for other reasons.

During their stellar survey, the star underwent its superflare. Its luminosity increased 10,000 times, allowing it to finally stand out from its neighbors.

Caught by surprise, the researchers quickly turned their attention to ULAS J224940.13-011236.9 during its proverbial 15 minutes of fame. They recorded the luminosity of the star over 146 days through various instruments on Earth.

Will the superflare of this star create life on any nearby exoplanets?

“It is amazing that such a puny star can produce such a powerful explosion,” explained Warwick researcher Peter Wheatley. “This discovery is going to force us to think again about how small stars can store energy in magnetic fields.”

The co-author of the paper, Wheatley taught astronomy and astrophysics at Warwick. He also headed the NGTS itself as well as the research team.

He and his colleagues explained that superflares provided a window of opportunity to examine the formation of life on exoplanets orbiting a flaring star.

Life depends on the presence of chemical reactions. In turn, these require a minimum level of ultraviolet radiation from the parent star.

ULAS J224940.13-011236.9 and other L dwarf stars are cool stars. They usually release infrared radiation, which is fainter and less hot than ultraviolet or visible light.

A superflare allows an L dwarf star to release ultraviolet radiation. The sudden burst might trigger chemical reactions on nearby exoplanets, resulting in the building blocks of simple but definitely alien lifeforms.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.