The manufacturing industry has recently welcomed what might prove a breakthrough technology. Scottish researchers showed off a new welding method that uses an incredibly fast laser to fuse together glass and metal.

Glass and metal are two of the most common classes of materials used for various purposes. Due to their very different thermal properties, it proved impossible to weld one with the other.

Manufacturers resorted to gluing glass and metal together. The adhesive became the weak spot of the combination.

Researchers at Heriot-Watt University overcame this long-standing limitation with their laser-based welding approach. Their new approach may transform the manufacturing sector, much like additive manufacturing (3D printing) technology did when it first came out.

It eliminates the need for adhesives to hold glass and metal while also increasing the durability of the fused materials. Welding also made it possible to create many more designs.

Aerospace, defense, healthcare, and optical technologies all stand to benefit from the ability to weld different types of glass with various types of metal.

“Traditionally it has been very difficult to weld together dissimilar materials like glass and metal due to their different thermal properties - the high temperatures and highly different thermal expansions involved cause the glass to shatter,” explained Heriot-Watt researcher Dr. Duncan Hand. (Related: The next asbestos? Carbon nanotubes, used in manufacturing, linked with cancer risk.)

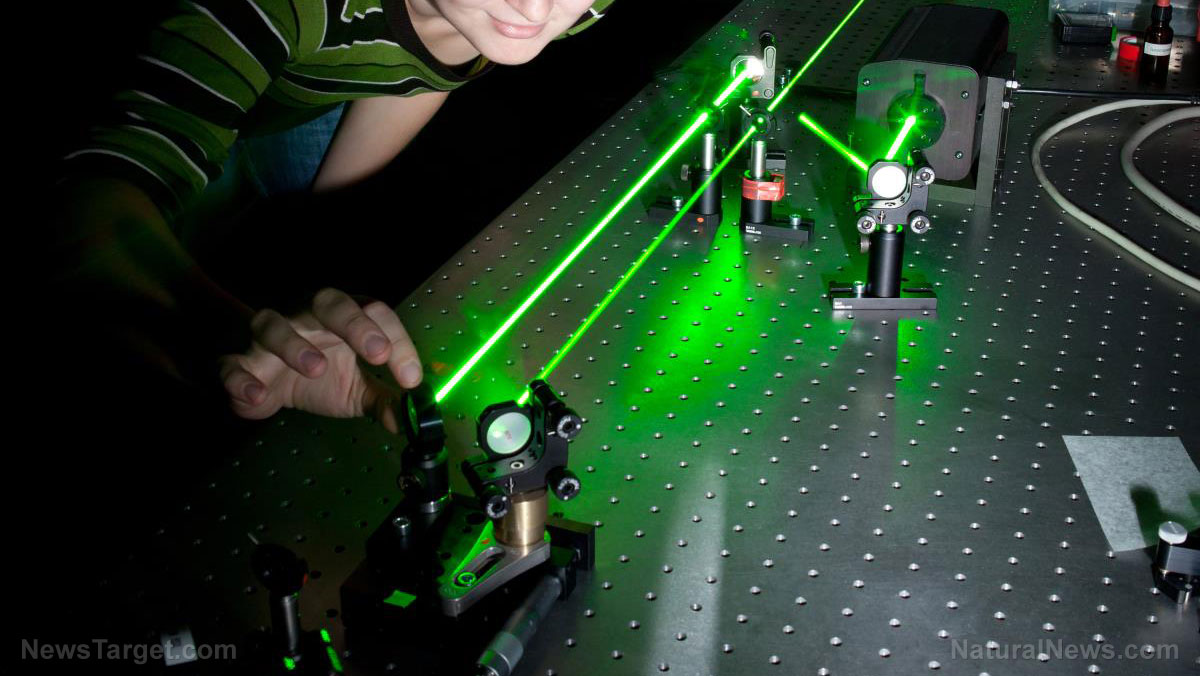

Welding glass and metal with an incredibly fast pulse laser

Hand is the director of the quintuple-university EPSRC Centre for Innovative Manufacturing in Laser-based Production Processes. He and his colleagues spent the last few years working on ways to fuse combos of very different materials with ultra-fast laser welders. They employed brief pulses of light, each of which lasted under a picosecond (one trillionth of a second).

Previously, picosecond pulsed laser welding was considered impossible. Glass and metal have very different thermal expansion coefficients, or the tendency of a material to modify its area, shape, and volume in reaction to a change in temperature.

The disparity in the thermal expansion coefficients means that glass will start to crack at temperatures that may not affect its partner metal and vice versa. This issue often crops up during glass welding.

The Heriot-Watt researchers also brought up another characteristic of their new laser welding technique – it didn't require much in the way of skill.

Current methods of laser manufacturing require the input of a skilled human worker. The new welding approach made it possible to convert the manufacturing process from a manual one to a cheaper automated method, thereby costing at least one person his job.

New laser welding method may revolutionize the manufacturing industry

Hand's team tested their picosecond laser welding technique on combinations of various materials. They used an infrared laser as the welding unit.

For glasses, they selected quartz, borosilicate glass, and sapphire. The last is blue-colored corundum, which sets the level 9 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness. Meanwhile, on the metal side, the researchers used aluminum, stainless steel, and titanium.

Hand reported that they succeeded in welding together all of the substances they tested. They put the glass and metal parts in close contact before concentrating the laser through the optical material.

The infrared pulse laser created a tiny and very intense spot at the interface between the two materials. An area that measured just a few microns in diameter received megawatt-level power.

“This creates a microplasma, like a tiny ball of lightning, inside the material, surrounded by a highly-confined melt region,” he explained. “We tested the welds at -50 C to 90 C (-58 F to 194 F) and the welds remained intact, so we know they are robust enough to cope with extreme conditions.”

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.