Could life forms exist and evolve on a planet that is subjected to frequent solar flare activity by a nearby star? A recent study by astronomers at Cornell University suggest that this is indeed possible, because the evolution of life forms on a planet facing deadly levels of ultraviolet (UV) radiation has happened before -- right here on Earth.

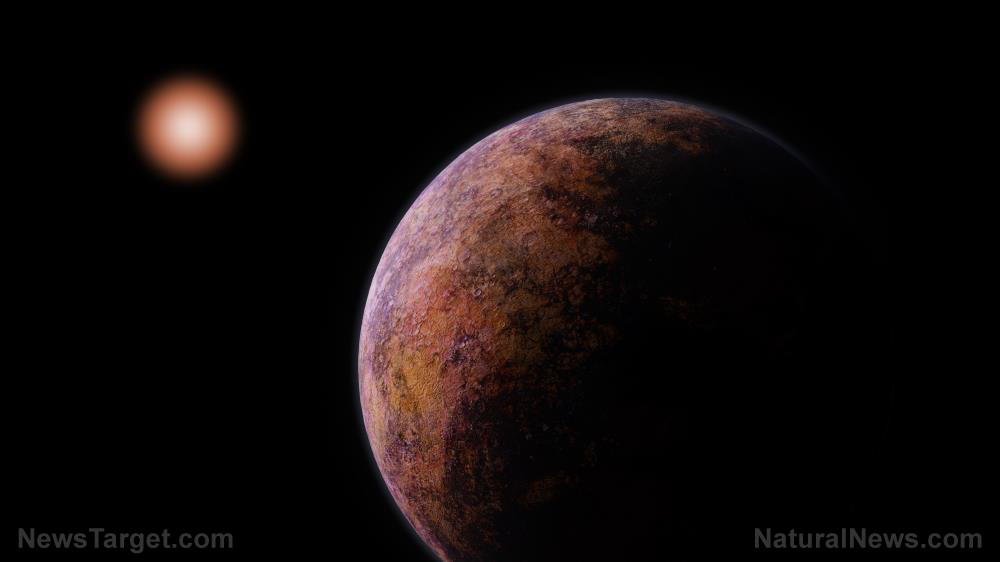

Over 3,200 exoplanets, or planets outside our solar system, have been discovered by astronomers in the last two decades. Some of these planets orbit what is known as a habitable or Goldilocks zone, a range of distances from a star with the right temperature for water to remain liquid. A planet that is too close to its parent star would be too hot, and water would evaporate, while a planet that is too far would be too cold, and water would freeze. Lisa Kaltenegger and Jack O'Malley-James focused their paper, "Lessons From Early Earth: UV Surface Radiation Should Not Limit the Habitability of Active M Star Systems," on nearby planets that are in the habitable zone: Proxima b, TRAPPIST-1e, Ross-128 b and LHS-1140 b.

These potentially habitable planets orbit a star that is different from the Earth's sun. Red dwarf stars are smaller than our sun, and they flare frequently, bathing their planets with high-energy UV radiation. Kaltenegger and O’Malley-James modeled various atmospheric compositions, from the ones that mirror present day Earth's atmospheric conditions to eroded and anoxic atmospheres -- those with very thin atmospheres and those without the protection of an ozone layer -- and calculated how much high-energy UV radiation reached the ground. High levels of radiation are known to be biologically damaging; biological molecules like nucleic acids may mutate or even shut down. Proxima b, a planet that was discovered less than three years ago, receives 250 times more x-ray radiation than Earth. How could life survive in such conditions?

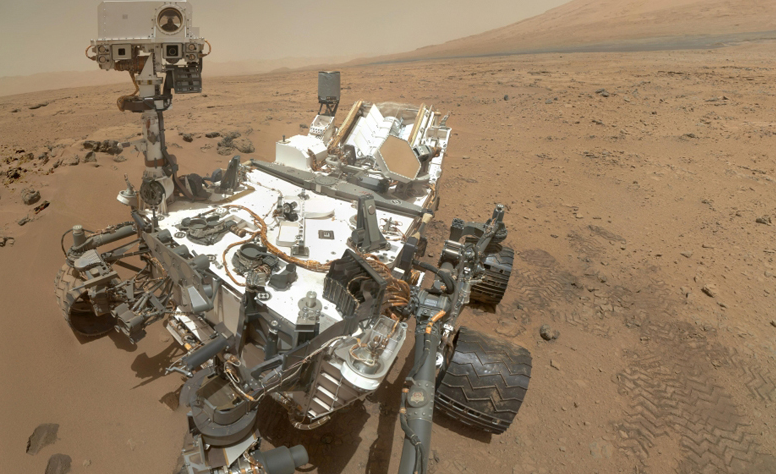

Kaltenegger and O'Malley-James looked toward Earth's own history for the answer. Nearly four billion years ago, Earth was a planet hostile to life as we know it today, bombarded by UV radiation that is similar to what Proxima b and other exoplanets orbiting M-type stars currently experience. Yet all life on Earth evolved from creatures that survived in these harsh conditions. Many organisms on Earth were able to cope with high levels of radiation using survival strategies like protective pigments, biofluorescence, or living under soil, water or rock. As O'Malley-James pointed out, "The history of life on Earth provides us with a wealth of information about how biology can overcome the challenges of environments we would think of as hostile." This suggests that UV radiation is not a limiting factor in the potential evolution of life on nearby exoplanets. (Related: NASA planning space expedition in 2069 to search for life on Earth-like planets).

The results of the study by Kaltenegger and O'Malley-James also suggest a tantalizing question: Are high levels of radiation – similar to those experienced by Earth in its earliest days – required for life to evolve? The models of the exoplanets the researchers studied showed that the surface UV radiation even for those with eroded and anoxic atmospheres remained at a lower level than early Earth levels, even during solar flares. This finding opens up two possible routes for further investigation: That life may be more likely to thrive in these exoplanets due to the relatively low levels of radiation compared to what early Earth experienced; or that life may be less likely to evolve because the required levels of radiation are not reached.

There are a multitude of factors that determine a planet's habitability. At this time, the composition of the atmosphere of the exoplanets nearest to Earth situated in the Goldilocks zone is unknown. What the study by Kaltenegger and O'Malley-James shows, however, is that high levels of UV radiation should not rule out exoplanets in the search for life outside of Earth.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.