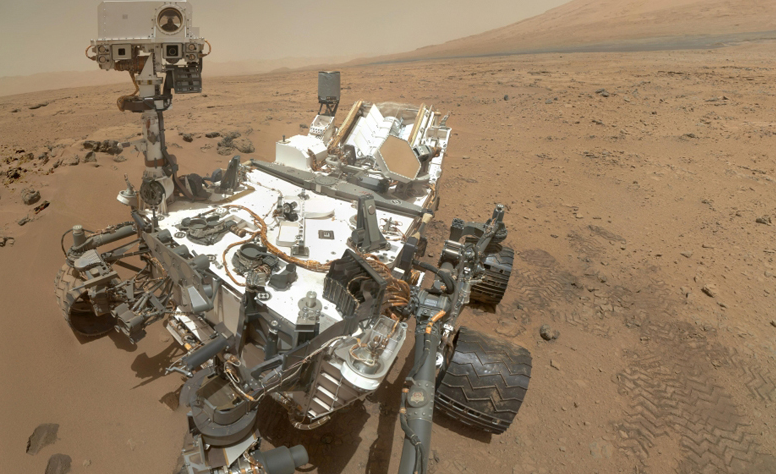

The leading theory behind the creation of the moon could also explain the eventual emergence of life on Earth. Texas-based researchers claimed that the unknown celestial body which hit our home planet in the distant past also deposited the ingredients necessary for life.

An ancient collision with an object the size of Mars is believed to have ripped out a large chunk of the young Earth. The chunk eventually settled into orbit around the planet and became its moon.

A new study suggested that the impact event also left behind a lot of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. These three "volatile" elements are considered vital to the formation of organic life.

The mantle of the young Earth was severely lacking in volatile elements. On the other hand, the core of the planet contained some carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur – but the two different parts of the planet did not interact with each other. The volatile elements in the core could not enrich the rest of the Earth.

Without these ingredients for life, the surface of the Earth remained barren. But everything changed when the collision took place. (Related: Towering blades of ice in Europa could get in the way of our search for alien life, scientists warn.)

Did Earth get its supply of life-giving elements from another planet?

An earlier theory revolved around multiple collisions with much smaller celestial objects. It posited that the Earth got bombarded by carbonaceous chondrite meteorites, which are known to contain isotopes of carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen.

Examination of these meteorites revealed ratios of volatile elements that seemed to match those on Earth. However, the ratio of carbon to nitrogen in carbonaceous chondrites turned out to be different from the ratio in the non-core part of the Earth.

Rice University researchers decided to look for another way to explain the arrival of life-giving elements on Earth. They went back to the idea of Earth colliding with another planet in the past.

Such an impact would have caused the cores and the mantles of both planets to merge together. If the other planet contained enough volatile elements, Earth would have gained them by virtue of "swallowing" the other celestial body.

There once was a planet the size of Mars with a sulfur-rich core – and Earth "ate" it

The Rice researchers decided to try their hand at making a candidate planet that could have enriched Earth. First, they recreated the high temperature and pressure needed to create the core of a planet.

Next, they combined metallic powder and various ratios of silicate powder within hollow capsules made from carbon graphite. The metallic material represented the iron-rich core of a planet, while the silicate powder stood in for the mantle.

The researchers changed the temperature, pressure, and amounts of sulfur in each setup to produce different versions of potential planets. Then, they evaluated the division of the elements between the core and the mantle of a planet.

Their findings showed that carbon was much less likely to bond with iron if there is a lot of nitrogen and sulfur present. Nitrogen, however, will readily bond with iron even with the presence of sulfur. In order to ensure that nitrogen stayed in the mantle, it should have a lot of sulfur.

These and other data were entered into a computer for simulation. Eventually, it came up with a scenario that could ensure the correct ratio of carbon to nitrogen on Earth.

The best candidate was a planet around the size of Mars. The core of this theoretical planet would be made up of 25 to 30 percent sulfur. "Swallowing" such a world would have given the Earth the right amount of volatile elements to support organic life plus a nifty moon.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.