Too much of anything often ends up being a bad thing. In the case of the exoplanets orbiting the star TRAPPIST-1, it's water. A shocking new study claims the seven planets are too wet to support life, according to a Space.com article.

Researchers from Arizona State University (ASU) believe the TRAPPIST-1 planets contain hundreds of times more water than is found in Earth's oceans. Some of them might have more than 1,000 times the water on our planet.

TRAPPIST-1 is fairly close to Earth as stars go, being 39 light-years away. It's a red dwarf star that's smaller and 2,000 dimmer than our Sun.

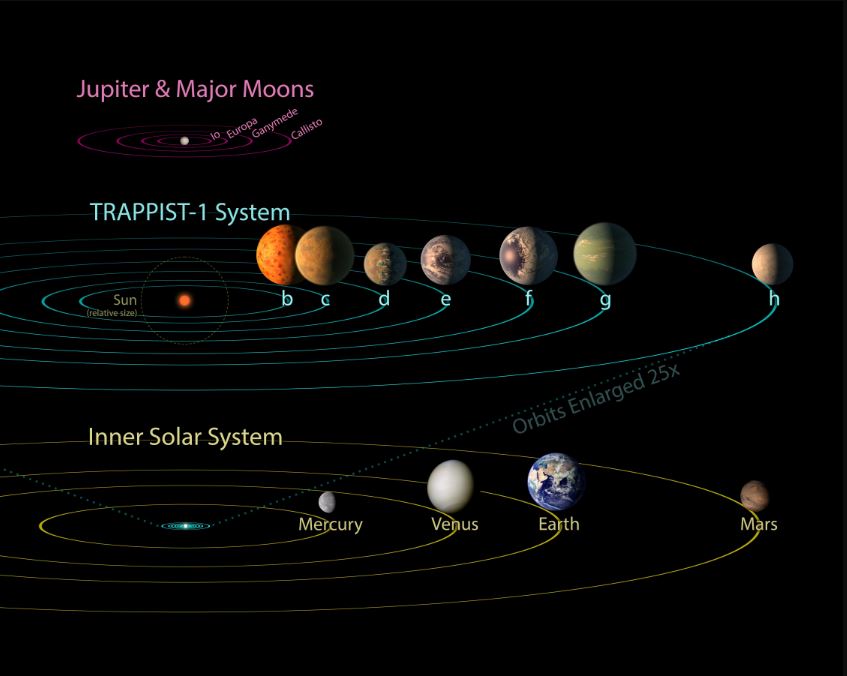

From 2016 to 2017, astronomers discovered seven exoplanets around it. Each of those planets is fairly close to Earth in size. They're also closer to TRAPPIST-1 than Mercury is to the Sun.

Three of these planets – labeled TRAPPIST-1 e, f, and g – are apparently within the habitable zone of their home star. That makes them likely candidates for hosting liquid water on their surfaces, which could mean they're also hospitable to life. (Related: NASA says that aliens live on Venus, but they’re only microbes.)

Astronomers have been able to calculate the volume and mass of these exoplanets. The ASU researchers used these estimates to create computer models for each planet save for TRAPPIST-1h, which remains fairly mysterious.

TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets are water worlds, probably lifeless, and frigid to boot

According to ASU researcher and lead author Cayman Unterborn, the models have predicted that water comprises about 10 percent of the two innermost planets, and at least 50 percent of the two outermost planets. The two middle planets are of course somewhere in between.

All six planets are much wetter than Earth, which is 0.2 percent water by mass. This leads Unterborn to believe that the TRAPPIST-1 planets are "water worlds" with no visible landmass.

The chances of finding alien life in water worlds are poor. The size of a biosphere relies on the amount of land exposed to weather. Less land means fewer nutrients like carbon and phosphorus to enter the sea, and no land means no nutrients.

In addition, water worlds may lack important geological processes that help produce life. There is so much water that its weight keeps the rock of the mantle below the waters. So, there are probably no surface volcanoes that generate carbon dioxide and other gases that trap heat in the atmosphere. That suggests the TRAPPIST-1 planets might also be colder than Earth.

Be thankful the Sun is a nice yellow star

There are other problems for planets that orbit red dwarf stars like TRAPPIST-1. One is the near-certainty of getting "tidally locked." If a planet is in the habitable zone of a red dwarf, it will always show the same face to the star. That side will always be much hotter than the other side.

A thick atmosphere could alleviate that problem since the air would circulate heat around the planet. But red dwarfs also have the bad habit of launching massive solar flares that can burn away the atmospheres of those unlucky planets.

The ASU study also uncovered clues about how the planets of the TRAPPIST-1 system formed and evolved. Right now, all seven exoplanets are inside the primordial "snow line." Any further out, and the planets would be cold enough for water to stay frozen as they formed.

However, it seems that planets f, g, and h were born outside the primordial snow line and moved closer towards the star as time passed. TRAPPIST-1b and c were born inside the boundary, while d and e's birthplaces are unclear.

If you'd like to read more articles about other distant planets that might possibly harbor life, visit Space.news.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.