Since World War I ended, the United States has started lending a hand to countries that are in need of assistance, starting with the reconstruction of post-war Europe, going all the way to Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

America led the world when it comes to giving foreign aid, but by 1994, America provided less assistance to developing countries than did Japan, and the same amount as France and Germany. In addition, the U.S.'s 1996 federal outlay of international assistance to other countries equated to only $6.6 billion – less than 0.5 percent of the total budget.

Most of the United States' financial assistance goes to food assistance, capital to multilateral banks, development aid, disaster relief, and refugee assistance. Admittedly, the U.S.'s actions have jumpstarted developing countries' own moves towards food self-sufficiency.

Small developing countries with income levels that are constantly on the rise, like South Korea or Malaysia, will experience no difficulties when it comes to importing food, even if they are unable to match food production at the domestic level. Other countries like Thailand will continue to export food and thrive in food adequacy. (Related: Amazing edible park in Irvine, Ca., stresses importance of food independence.)

Continued food self-sufficiency can be credited in the decrease of the proportion of hungry people in East Asia to 16 percent from 40 percent even while their population increased by 500 million within the last 25 years. Its food needs are expected to increase sharply over the coming decades with a projected population of almost three billion by 2050.

The situation in Latin America is optimistic, albeit with some caveats. The proportion of the malnourished people in the continent declined to 14 percent from 18 percent over the past 25 years, although at the expense of the destruction of its natural forests.

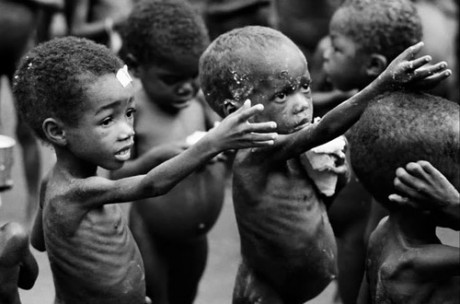

Africa, on the other hand, has already reached the point when population growth rates have already exceeded food production growth rates, resulting in hunger whenever bad weather, civil unrest, or war decides to poke his ugly head in. It is currently depending on imports for around 25 percent of its grain consumption, a rate that has increased over the past 30 years as per capita food production has dropped.

One could say that the food independence assistance that the U.S. provides developing countries also brings empirical benefits to America. All the major crops in the U.S. – corn, potatoes, barley, rice, and wheat, among others – are endemic to other countries. The genetic variation that is the basis for plant breeding that created current high-yielding crop varieties in the United States was obtained from other countries.

This makes the genetic variation that is available in the U.S. limited; when a new pathogen threatens the existence of such crops, there is the possibility that naturally-occurring resistance in the germ plasm that is available here won't be enough to conquer the new pests. So scientists and agriculturists look for the cure in international agricultural research centers, and America's financial aid to sustain such centers gives the United States a moral claim to those resources.

As a matter of fact, Phillip Pardey and his colleagues at the International Food Policy Research Institute has reported that by the early 1990s around one-fifth of the total U.S. wheat acreage and more than 70 percent of the American rice acreage – at a combined value of $3.5 billion between the years 1970 and 1993 – originated from varieties that were produced by the international agricultural research centers.

In comparison, the United States gave $150 million to international wheat and rice centers and less than $1 billion to all the international centers in the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) around that time.

“These improvements in countries around the world, in health and in income levels – there has also been a big shift to democracy...are helping to bring more capable states and governments that are quite helpful to us. If we want to enhance our own security around the world we need to be able to work with capable governments and states,” said Stece Radelet, a professor and director of the Global Human Development Program at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

“There are many, many surveys that are taken, that Americans believe that we spend something like between 10 percent and 20 percent of the federal budget on foreign aid. And in fact we spend less than one percent of the federal budget. It's a tiny share of our budget that we contribute to fighting poverty and hunger and disease around the world,” Radelet added.

New goals for the U.S. in its food assistance advocacy

The major goal for the United States is to help developing countries acquire their own agricultural knowledge, often in partnership with other entities, as time and again it has been proven that rising agricultural productivity is vital to economic development in every country that was once not self-sustaining.

The countries that the U.S. sees as the most challenging when it comes to this goal include Bangladesh, China, and India and areas such as Java, Malawi, and other highland areas of southern and eastern Africa. This is attributed to the fact that the international system is remiss in its duties to help African organizations address soil management, pest management, and water challenges.

Poor roads, poor transportation, and poor marketing systems in Africa also mean that fertilizers are more expensive in that part of the world. The United States stresses the need for public investments in good roads and transportation systems, plus market information systems that would establish the development of private traders, thereby decreasing the cost of marketing of both inputs and products.

For more stories on food independence, food surplus, and the ways the United States has been championing these causes, visit FoodSupply.news.

Sources include:

Please contact us for more information.